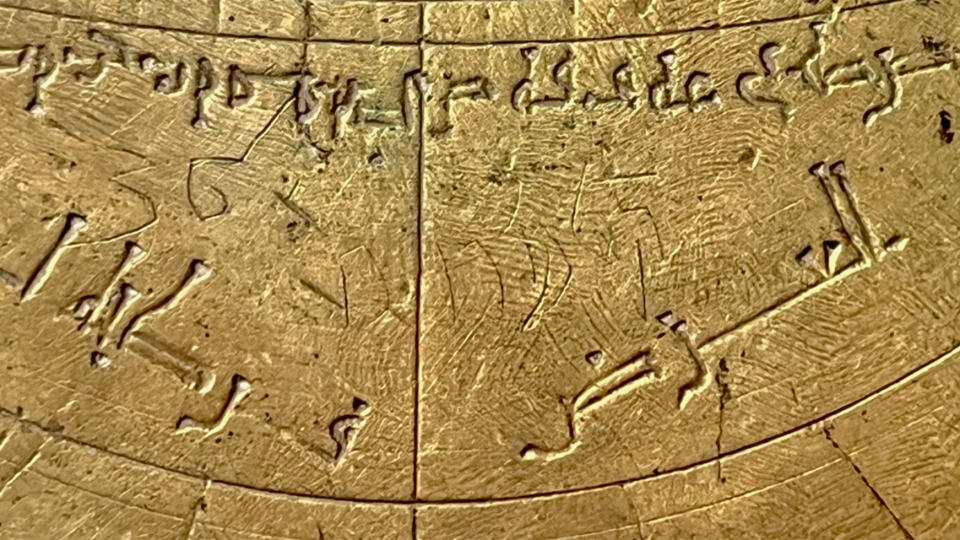

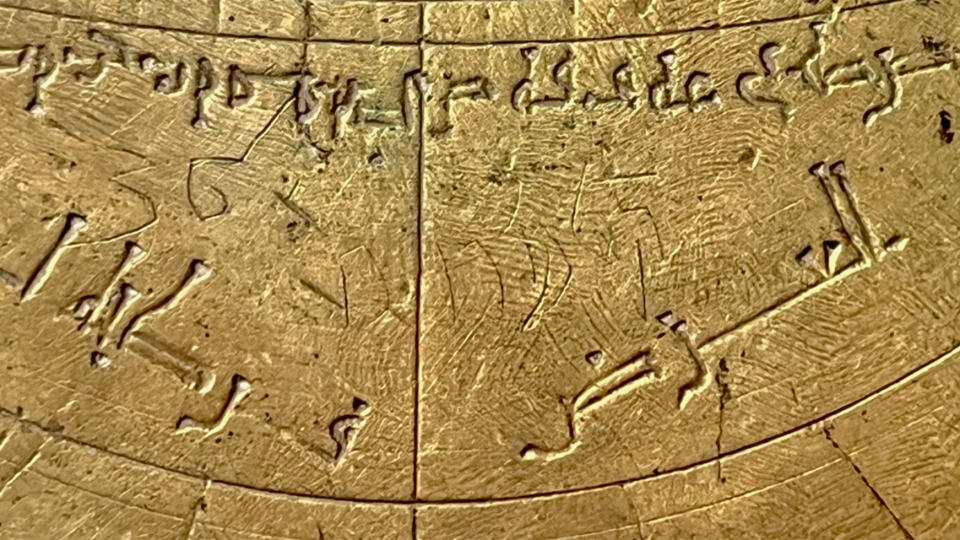

An 11th-century astrolabe, a device used to accurately calculate date and time based on star positions, housed in a museum in Verona, Italy, is clear evidence of scientific exchange and cooperation between Muslim, Jewish and Christian peoples, a new study finds. puts .

astrolabe It stands out because it was built by Muslim craftsmen and then passed through the hands of Jewish and Christian users who translated and modified the handheld device over the centuries. An astrolabe this widely shared, dating back almost a thousand years, is an extremely rare find.

The true value of the bronze astrolabe, which had languished for decades in the archives of the Fondazione Museo Miniscalchi-Erizzo in Verona, was not realized until the museum’s curator, Giovanna Residori, became curious and drew the attention of Federica Gigante, a historian at the University of Cambridge. Material and intellectual exchanges between the Islamic people and Europe.

Relating to: What did ancient people know about astronomy?

“The current curator thought it was an intriguing object and wanted to learn more about it,” Gigante said. said. space.com. “I happened to see it on the museum’s website, so it was a happy coincidence.”

After examining the astrolabe, Gigante was struck by how complex the history of this particular device was.

Astrolabes were invented by the ancient Greeks, but no astrolabes have survived since then. In contrast, the earliest examples date from the late 8th century and were built by. Arab astronomersLeading the world in terms of scientific skills at the time.

Astrolabes are made from a disk around the edge of which time or angular degrees of separation are marked. Attached to this disk are one or more circular plates, each plate corresponding to a specific latitude, and above it is another plate called a rete (pronounced “ree-tee”), above which is a chart showing the brightest spot. stars in the sky. The idea is to rotate the grid so that the position of the stars matches that in the sky, and then use the clock scale around the frame to determine the time.

Astrolabes were designed by Muslim craftsmen specifically with religious use in mind.

“Every mosque would have one,” Gigante said. “This makes perfect sense, because the main function of the astrolabe is to tell time, and this is what the muezzin does from the minaret, which is to read the prayer time.”

There are a dozen or so examples of Arab-made astrolabes in museum collections around the world, but what makes the Verona astrolabe stand out is that it also contains inscriptions in Hebrew and a western language used in Christian countries at the time; in this case probably Italy.

Gigante says the astrolabe was probably built in Spain in the late 11th century. But he can’t be sure exactly when it will happen. “The star positions are so inaccurate that I was able to extract the dates from them,” he said.

Soil wobbles on its axis, a movement called motion We see that the positions of the stars relative to the north pole change in a cycle that lasts 26,000 years. Over the millennia since the astrolabe was built, stars have shifted about 14 degrees relative to a fixed background. But Gigante found that trying to match the sky with positions on the astrolabe to determine when the astrolabe was made did not work because star positions on the astrolabe were not as accurate as modern measurements.

Instead, Gigante studied ancient stellar coordinate tables from which the astrolabes of this era were derived. He focused on those in Andalusia, a Muslim-ruled region in what is now Spain. In Andalusia, both Muslim and Jewish people lived side by side and all spoke Arabic. The Verona astrolabe has an inscription in Arabic that reads “For Isaac”. […]/the work of yūnus.” In English these names are Isaac and Jonah, probably Jewish nicknames written in Arabic, hence Gigante’s focus on Andalusia.

“If we think about what Spain was like in the 11th century, there were many different observatories where attempts were made to create charts of star coordinates and planetary positions, and these were always working groups of scientists, consisting of Jews and Muslims, working together with the other,” says Gigante. .

Although he could not identify a specific table of star coordinates that provided information about the Verona astrolabe, he found a similar table dated to Andalusia in 1068. This is supported by further inscriptions on one of the reversible plates, stating that they are for the latitudes of Cordoba and Toledo, both cities in the region.

However, at some point the astrolabe seems to have changed hands. A second plate was added with an Arabic inscription saying it was for use somewhere in North Africa, modern-day Egypt, or Morocco.

Relating to: Mariner’s astrolabe from a 1503 shipwreck is the world’s oldest

After this the astrolabe received other changes. The Arabic signs were crossed out and translated into Hebrew, the language of the Jewish people in the rest of the world. After this, faint numbers written in a western language were also engraved on the disk, before the astrolabe eventually fell into the hands of Ludovico Moscardo, a 17th-century nobleman living in Verona. This collection became part of the collection at the Moscardo Museum, which was incorporated into the Fondazione Museo Miniscalchi-Erizzo in 1964, eventually attracting Gigante’s attention.

Astrolabes were the smartphones of their time. “Every educated person would have one, especially those who studied astronomy or astrology,” Gigante said.

Half of these users, such as the muezzins on their minarets, used them to take astronomical readings for religious sites. The other half used them for astrological purposes. Astronomy and science in the 11th century, when our understanding of the heavens was limited astrology It was considered the same thing.

RELATED STORIES:

—Stonehenge’s summer solstice orientation is seen in spectacular photographs at monuments across the UK

—Strange anomaly in sun’s solar cycle discovered in centuries-old texts from Korea

—Famous astronomers: How these scientists shaped astronomy

“I think that when the astrolabe came into the hands of Jews and Christians, it was used for astrological rather than religious purposes, although the monks also used the astrolabe for prayer times,” Gigante said.

Astrolabes with Hebrew inscriptions are extremely rare; Gigante knows of one in the British Museum in London but not another, although most have probably been lost to the ravages of time. However, their rarity emphasizes that most astrolabes from this era were of Muslim origin and were used only by Muslims. The Verona astrolabe is therefore of historical importance because its origins are equally Islamic, Jewish and Christian.

Given the current tragic events in the Middle East, this is a timely reminder that different peoples could live together and share knowledge in the past.

Gigante discusses his findings in an article published March 1 in the journal Nuncius.