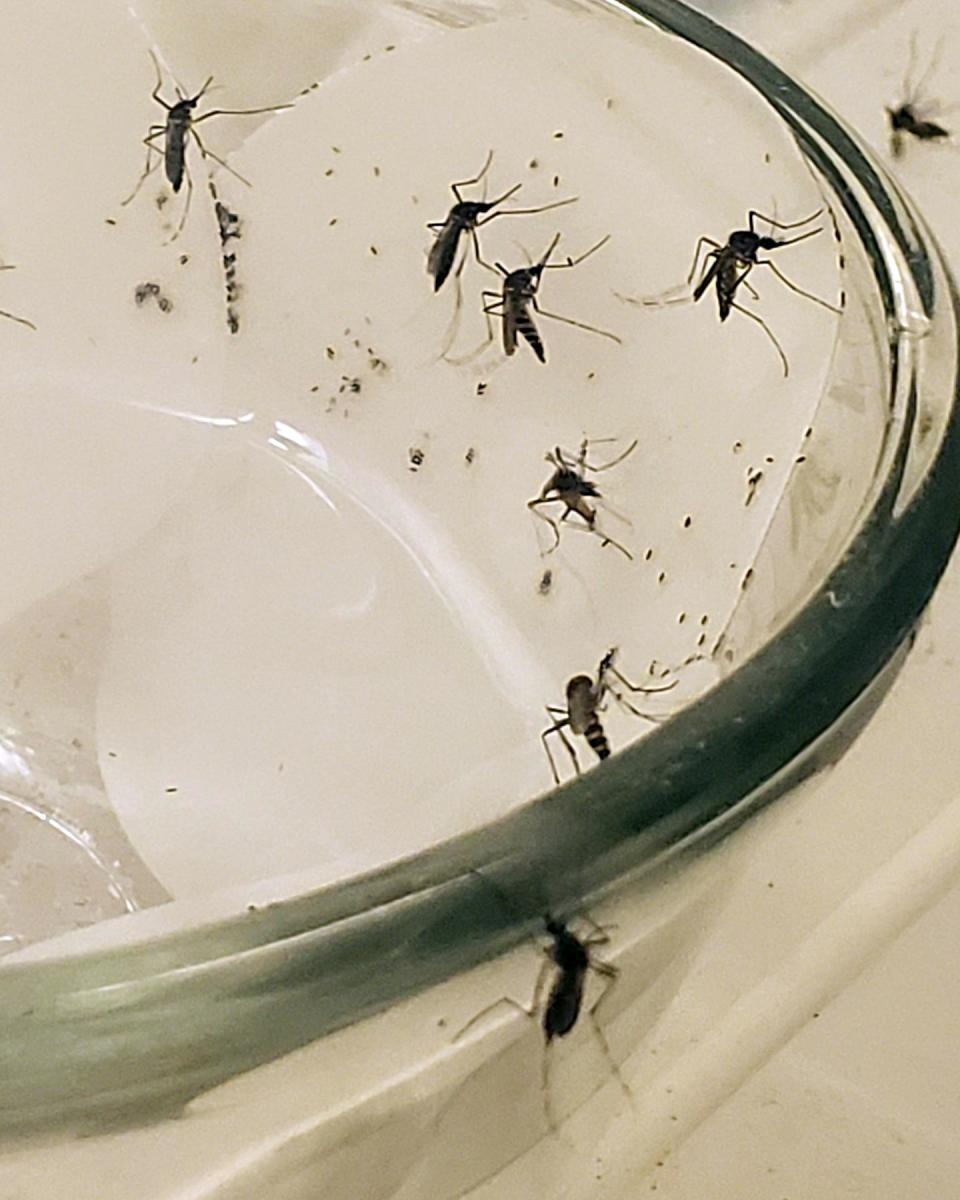

Aedes aegypti Mosquitoes, one of the most common species in the United States, love all things human. They like our body temperature and scent, which helps them find us. They like to feed on our blood so that their eggs can mature. They even love all the standing water we create. Open containers, old tires and garbage heaps collect water and are perfect for breeding.

With the arrival of warm weather in the south of the USA, mosquito breeding season has begun.

Considering all options Aedes How do these cosmopolitan mosquitoes, where females live in urban areas, find the perfect environment to lay their eggs? Scientists previously thought this was a solitary act, but now research shows that women Aedes aegypti Mosquitoes, the main carriers of diseases such as Zika, dengue, chikungunya and other viruses in the United States, can rely on each other to ensure good inspection of their breeding grounds.

Our Tropical Genetics Laboratory at Florida International University has discovered a new behavior in which these mosquitoes work together to find suitable egg-laying sites. These findings, recently published in Communications Biology, show that mosquitoes regulate their own population densities at breeding grounds; It’s an idea that could inform future mosquito control efforts.

Where and why do female mosquitoes cluster?

Scientists know that female mosquitoes can be selective about where they lay their eggs. Aedes aegypti Look for man-made breeding sites with relatively clean water, such as birdbaths, tires, or even waterlogged garbage dumps. But given two equal options, you can expect them to be evenly spread between the two.

In contrast, when we released females in a two-choice test in which both breeding site options were equivalent, we found many times more mosquitoes in one room than in the other. Moreover, this occurred regardless of where the preferred compartment was positioned, whether mosquitoes could contact water, or whether mosquito eggs were present in the breeding grounds.

Female mosquitoes were clearly following each other in small groups towards a breeding ground; This was also a newly discovered behavior. Aedes aegypti We call this aggregation.

Apparently the insects preferred not to leave their eggs alone. When we tested 30 mosquitoes in our experiments, they chose one site over another by a 2 to 1 margin. However, this changed when the test population increased to over 30 mosquitoes. When we tested 60 or 90 women, the cluster disappeared.

This tells us that females can regulate their own density in breeding grounds; This is probably a mechanism that limits larval competition.

Mosquitoes smell each other

Mosquitoes perceive the world largely through smell, using three families of olfactory receptors. These receptors detect odors when females choose where to lay eggs. So how do females sense each other to regulate their density in breeding grounds?

We first investigated this question by placing 15 mosquitoes at one of our two test breeding sites. Although we had previously observed that mosquitoes preferred not to leave their eggs alone, other females looking for a place to lay eggs preferred the empty space over the space already occupied. Something was driving them away from the occupied breeding ground; We speculated that carbon dioxide might be an important clue for mosquitoes at each stage of their life cycle.

While female mosquitoes suck blood, they fly towards the smell of CO₂, which all vertebrate animals breathe in and release through their skin. After feeding, they fly away, presumably to avoid the risk of being killed by the host.

Mosquitoes also emit CO₂, and normally other mosquitoes can smell CO₂ thanks to a receptor component called Gr3 in their olfactory organs. But when we released mutant females lacking a functional Gr3 receptor to search for an egg-laying site in our two-site test, we found that these insects, which cannot detect CO₂, were willing to lay their eggs in busy breeding grounds. This suggests that normal mosquitoes may be avoiding the oviposition site they are occupying because they smell the CO₂ emitted by mosquitoes already there.

To confirm this, we presented two empty breeding grounds to females looking for a place to lay eggs. However, we did increase CO₂ levels around one of the sites to between 600 and 750 parts per million, compared to the normal level of about 450 to 500 ppm at the other site. we found it Aedes aegypti females avoided unoccupied areas where CO₂ was high. This behavior appears to be designed to prevent occupied breeding grounds from becoming overcrowded.

Overall, we found that two families of receptors are involved in interactions between them. Aedes aegypti while females search for breeding grounds. Olfactory receptors detect an unknown odor that attracts females to a particular area; Taste receptors detect CO₂, which drives females away from breeding grounds when carbon dioxide levels are high. The balance between these attractive and repulsive odors will ultimately determine whether the female will choose or avoid a particular area.

Implications for mosquito control

Suppressing mosquito populations in urban areas using biolarvicides (pesticides made from live bacteria that are toxic to mosquito larvae) is the primary control strategy to limit the spread of deadly diseases such as West Nile virus and Zika virus. This is especially true for: Aedes aegyptiIt is the most common urban mosquito species that breeds in artificial breeding grounds created by humans. Other control tactics, such as spraying pesticides over large areas, target beneficial insects as well as mosquitoes and can be controversial.

knowing that woman Aedes aegypti They use social cues to choose the best breeding grounds for their young and leave when the breeding site becomes too crowded, leading to new control measures. Interrupting the female mosquito’s reproductive cycle will reduce the spread of mosquitoes and the spread of diseases carried by these insects.

This article is republished from The Conversation, an independent, nonprofit news organization providing facts and authoritative analysis to help you understand our complex world. Written by Kaylee Marrero Florida International University; André Luis da Costa da Silva, Florida International Universityand Matthew DeGennaro, Florida International University

Read more:

Kaylee Marrero receives funding from the National Institutes of Health.

Andre Luis Costa-da-Silva receives funding from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the Southeastern Center of Excellence in Vector-Borne Diseases, and the National Institutes of Health. The views expressed in this article are his own.

Matthew DeGennaro receives funding from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), the Southeastern Center of Excellence in Vector-Borne Diseases, and the National Institutes of Health. The views expressed in this article are his own.