Sign up for CNN’s Wonder Theory science newsletter. Explore the universe with news about fascinating discoveries, scientific advancements and more.

It was the end of summer 2850 years ago. A hilltop village on a marshy, slow-moving river running through the wetlands of eastern England has been destroyed by fire. Tightly packed roundhouses built just nine months ago from wood, straw, grass and clay go up in flames.

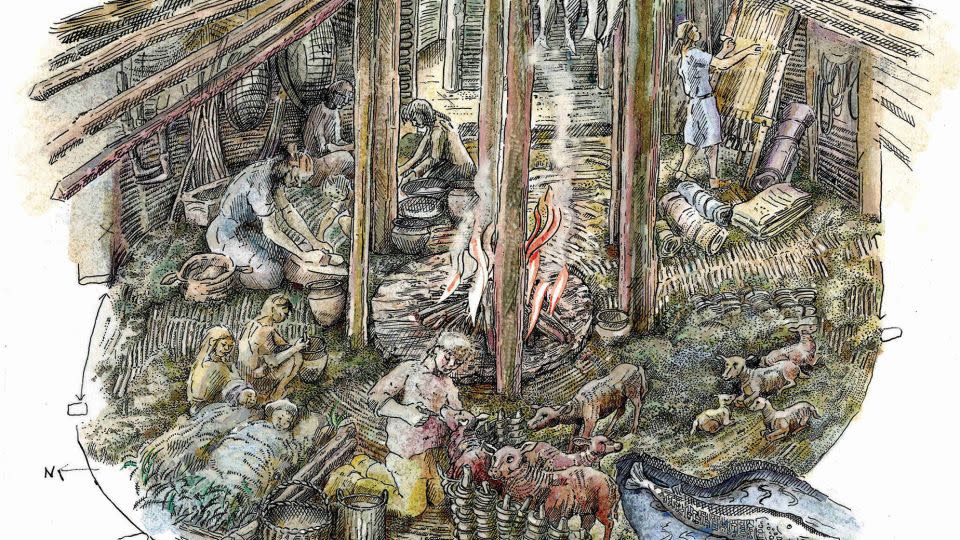

The residents flee, leaving all their belongings behind, including a wooden spoon in a bowl filled with half-eaten porridge. There is no time to save the fat lambs that were trapped and burned alive.

The scene is a vivid and poignant photograph taken by archaeologists of a thriving community in late Bronze Age Britain known as Must Farm, near what is now the town of Peterborough. On Wednesday, the research team published a two-volume monograph describing the painstaking $1.4 million (£1.1 million) excavation and site analysis in the Cambridgeshire county.

Described by relevant experts as “archaeological nirvana”, the site is said to be the only place in Britain that meets the “Pompei proposition”, a reference to the city forever frozen in time by the eruption of Mount Vesuvius in AD 79. He gave unique information about Ancient Rome.

“In a typical Bronze Age settlement, if you have a house, there are probably a dozen or so post holes in the ground, and these are just dark shadows of where they once stood. If you’re really lucky, you’ll find a few pottery shards, perhaps a pit with a bunch of animal bones in it. This was the exact opposite of the process. It was truly incredible,” said Chris Wakefield, an archaeologist at the Cambridge Archaeological Unit at the University of Cambridge and a member of the 55-strong team that excavated the site in 2016.

“All of the ax marks had been used to shape and shape the wood. It all looked new, as if it had been done by someone last week,” added Wakefield.

The site’s remarkably preserved state and context enabled the archaeological team to gain comprehensive new insights into Bronze Age society; These were findings that could overturn existing understandings of what daily life was like in Britain in the ninth century BC.

Must farm and be a mystery

Dating to eight centuries before the arrival of the Romans in Britain, the site revealed four roundhouses and a square gateway structure standing approximately 6.5 feet (2 metres) above the riverbed and surrounded by a 6.5-foot (2 metres) hedge. sharpened messages.

Archaeologists believe the settlement was probably twice as large. But quarrying in the 20th century destroyed other ruins.

Although charred by fire, the remaining buildings and their contents were exceptionally well preserved due to the anoxic conditions of the swamps or wetlands and contained many wood and textile items that rarely survive in the archaeological record. Together, traces of the settlement paint a picture of comfortable domestic life and relative abundance.

Researchers unearthed 128 ceramic artifacts, including jars, bowls, cups and cookware, and were able to infer that 64 pots were in use at the time of the fire. The team found some neatly nested stored containers. Textiles made from flax found in the region had a soft, velvety texture and neat seams and hems, but it was not possible to identify individual pieces of clothing.

Wooden artifacts included boxes and bowls carved from willow, alder and maple, 40 coils, many of which are still attached, various tools and 15 wooden buckets.

“One of these buckets… had a lot of cutting marks on the bottom, so we know that when Bronze Age kitchen people needed an improvised cutting board, they turned that bucket upside down and used it as a chopping tool.” It came to the surface,” Wakefield said.

“It’s those little moments that come together to present a richer, fuller picture of what’s going on.”

The circumstances of the incident that brought everything to a halt are still a bit of a mystery. Researchers believe the fire broke out in late summer or early autumn because skeletal remains of lambs raised by a household indicate that animals typically born in the spring were three to six months old.

But it remains unclear what exactly caused the devastating fire. The fire may have started accidentally or deliberately. Researchers have unearthed a pile of spears with shafts more than 10 feet long at the site, and many experts think warfare was common at the time. The team worked with a forensic fire investigator but ultimately were unable to identify a specific “definitely” clue pointing to the cause.

“An archaeological site is like a puzzle. In a typical facility, you’d have 10 or 20 out of 500 items,” Wakefield said. “There were 250 or 300 items here, but we still don’t have the full picture of how this massive fire started.”

Emerging ideas about Bronze Age society

The contents of the four preserved houses were “remarkably consistent.” Each had a toolbox containing sickles, axes, gouges, and hand-held razors used for cutting hair or fabric. With a floor area of almost 538 square feet (50 square meters) in the largest, each of the residences appeared to have distinct activity zones comparable to rooms in a modern home.

Not all items were suitable for practical use, such as 49 glass beads and others made of amber. Archaeologists also unearthed a female skull that was smooth to the touch, possibly a souvenir of a lost loved one. Some of the items found by the researchers will be exhibited in the exhibition titled “Kitchen Farm, Bronze Age Settlement Presentation” at the Peterborough Museum and Art Gallery starting April 27.

Laboratory analysis of biological remains revealed the types of food the community once consumed. The last course was contained in a pottery bowl imprinted with the fingerprints of its maker; porridge of wheat grains mixed with animal fat. Chemical analysis of the bowls and jars showed traces of honey as well as deer; This suggested that the people using the plates might have liked the venison coated in honey.

Old feces found in waste heaps beneath the site of the houses showed that the community kept dogs that fed on leftovers from their owners’ meals. And human fossilized poop, or coprolites, showed that at least some inhabitants suffered from intestinal worms.

Waste heaps or dumps were a line of evidence showing how long the area had been occupied; A thin layer of trash indicated that the settlement had been built nine months to a year before it went up in flames. Wakefield said there are two other factors that support this logic.

“The second was that most of the wood used in construction was out of season, still green, and had not been in place for a long time,” he said.

“The third is the lack of insect and animal species associated with human settlement. “It wouldn’t have taken long for the beetles to get in… but there is no evidence of this in any of the over 18,000 timbers.”

The fact that the rich and diverse site has only been in use for a year has disrupted the team’s “visions of everyday life” in the ninth century BC and may suggest that Bronze Age societies were perhaps less hierarchical than traditionally thought. According to the 1,608-page report.

“We see here only a year’s worth of material, not a lifetime’s accumulation,” the authors said in the report. “It suggests that artifacts such as bronze tools and glass beads were more common than we thought and that their availability may not have been restricted.”

For more CNN news and newsletters, create an account at CNN.com