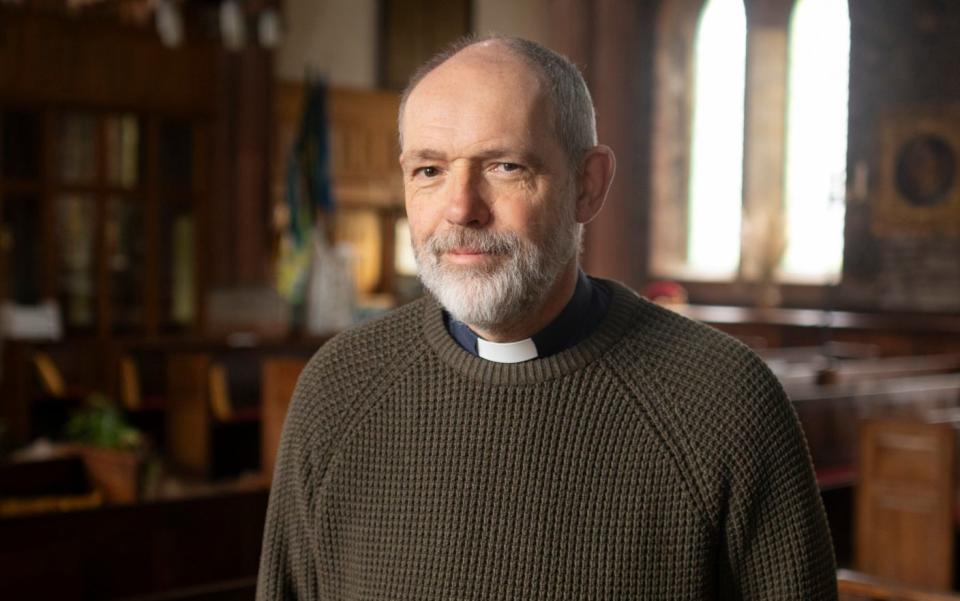

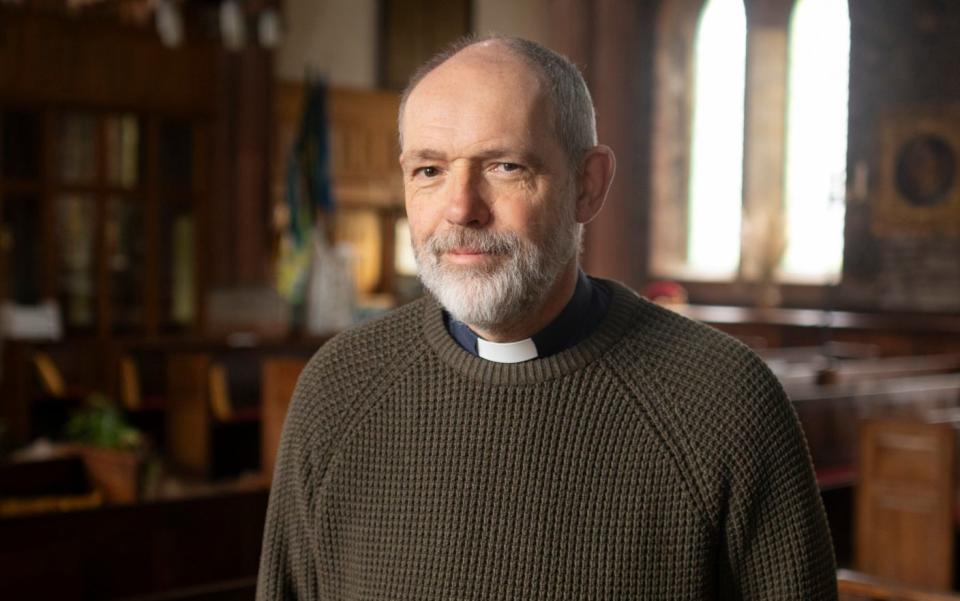

On Sunday, the Rev. Greg Smith, rector of St George’s in the small south Shropshire market town of Pontesbury, will lead services at three of the six far-flung churches that form the charity or extended congregation he presides over.

Two other clerics will assist him with the rest; one of these, St Luke’s, Snailbeach, is now designated a “festival church”, meaning its use is so low that it is only open on holy and solemn occasions.

“I have 6:30, nine and 10:30 in the morning,” Smith says. “This will mean a lot of running around in the car, running from one church to another, never spending time with people, not being able to properly prepare.”

It wasn’t what he signed up for when he arrived in rural Shropshire three years ago after 22 years in a suburban neighborhood in Coventry. “If you had told me before I started this job that I would be responsible for six churches, I would have said, ‘That’s not me.’ “It was a pretty good training.”

On Sunday, he expects a significant increase of 40-50 in pews at St George’s, a 13th-century stone-built church with space for 400, as well as an increase in the charity, which has weekly congregations in all six churches. The number of churches is around 120. Outside of major holidays, he admits that the small numbers in the queues can sometimes overwhelm him.

“In one of my churches [he doesn’t want to name names] The total worshiping congregation is seven out of a village of 50 households. You can’t always see them all the time [he leads a service there] twice a month. “If we started from scratch, there would be no way to put a church there.” But there is one, and the question of what to do with it touches on larger questions about the future for the whole Church of England.

It was a yearning for a new challenge that persuaded Smith, who is married to Fran and has four adult children and three grandchildren, to come to Pontesbury. He definitely found one.

“I hadn’t particularly considered doing rural ministry, but I’m a keen walker and knew the Shropshire Hills well. “We loved spending time in Wales and it was just over the border so we came.”

He was swimming against the tide in the Church nationally. This Easter has seen reports of a crisis in pastoral services, with congregations closing (before Smith arrived, Pontesbury church had its own vicar, while another vicar was appointed for the other five churches) and vacancies rising.

In the diocese of Truro in Cornwall, the local branch of campaign group Save The Parish (STP), set up in 2021 to preserve the Church of England’s 1,000-year-old network of parishes, claims there are just 38 churches in their largely rural diocese. With 19 vacancies filled, paid clergy remain in office and a planned restructuring is underway to fill the cracks created by appointing “oversight ministers” to “giant aids” that will further weaken the Established Church’s vital presence in the church. The heart of every society.

Hugh Nelson, acting bishop of Truro, questioned the STP’s figures and pointed out that eight new clergy appointments had been made in the last three months. But he acknowledged there was still a big problem with “the real difficulty of recruiting clergy right now.”

The impression that the Church of England’s rural ministry is on its knees is not one accepted by Greg Smith, who in his spare time does not just drive between churches but runs a food bank and two social cafes. The Young People and Bereavement Service is preparing a report on the issue for its local bishop.

He admits that the life he leads is brutal. There are currently 72 clergy in the diocese of Hereford, which includes Pontesbury, shouldering the burden of parish work in 406 churches with nine vacancies, so it is in a better position than Truro. But three-quarters of the priests licensed to administer liturgy in the diocese are over 50 years old.

And the fact that 90 per cent of the churches in the diocese are listed buildings does not make the workload on them any easier. “Maintaining a listed building is a tough job, but I have five and they all have big bills on the door,” says Smith.

At St George’s, a fee of £250,000 is expected to repair the stained glass at the east end of the church. The next village, Holy Trinity in Minsterley, needs a similar amount.

“There are some grants available, but it’s a never-ending load of paperwork.”

In the past, some of this form-filling work fell on church staff, volunteers from the congregation who often had professional expertise. But a report published earlier this month found that a quarter of CofE congregations no longer have a single churchwarden.

But the sense of crisis in the Church of England this Easter is not just being felt in rural areas. Sunday attendance remains a fifth below pre-pandemic levels, according to Telegraph analysis, exacerbating a long-term decline from 1.2 million in 1986 to more than halving over the past 40 years.

Figures from the 2021 census offer little hope that this will reverse any time soon. Only 46.2 percent of the population identifies as Christian (not all Anglicans, of course), compared to 59.3 percent a decade ago. And while 72.2 percent of people over 65 identify as Christians, only 31.2 percent of those ages 25 to 34 do so.

Such a drastic drop in the number of worshipers inevitably means a drop in the amount of money put into the church’s collection plate each week, putting ever-greater pressure on diocesan authorities and the national church to address such shortfalls. He does this.

In 2022 the Church Commissioners announced a £3.6bn package to be spent over 10 years on frontline work in the Church of England; £1.2 billion of this package will be distributed between 2023 and 2025. However, there are some conditions. There is increasing pressure to close and consolidate churches where congregation numbers no longer cover the cost of a full-time pastor.

Telegraph analysis shows 28 congregations will be closed or merged in 2023; This often leaves regular attendees dismayed, while a total of 641 churches have closed since 2000, accounting for 4 percent of the total.

The Rev. Marcus Walker, national chairman of the Save the Parish group and a member of the General Synod, the Church of England’s decision-making body, sees this as potentially an “apocalyptic spiral”.

“Just as night follows day,” he warned, “if you close congregations and reduce clergy, the number of people who can return to the Church will decrease.”

It specifically calls for new investment to support the parish network if disaster is to be avoided, but questions about whether new funds can be found or whether the funds promised by the Church Commissioners will be delivered have been raised by another high-profile report that has just emerged. Before Easter.

A high-profile panel has called for the funding allocated by Church Commissioners to be increased from £100 million to £1 billion to redress Anglicanism’s historic involvement in the slave trade.

If the recommendation of the panel, chaired by Bishop Rosemarie Mallett of Croydon, is accepted, this cost will significantly reduce the ability of Commission members to give local churches the support they are now clamoring for to keep things going.

The issue of reparations, in particular, is proving to be highly divisive.

Among the many comments sent to the Telegraph by regular church-going readers in recent weeks, Maggie Brennan’s was reminiscent of many others.

“The Church of England has lost sight of its core values and lost public trust and, like all other institutions that are now badly failing, has indulged in some woke groupthink.” Another reader, Jo Pearson, suggests: “The Church of England abandoned its people, not the other way around.”

In Shropshire, Greg Smith offers a different perspective on the issue of reparations and his claim to pursue a woke agenda on other issues such as sexuality and same-sex marriage.

“I’m not saying these aren’t important, but I can say these aren’t conversations I’m having locally. “The only people who talked to me about slavery reparations were other clergy.”

So what issues do his parishioners raise with him?

“People are doing a lot more exercise on maintaining balance. [church] to warm up and enable children and the younger generation to worship with us. “The national church can feel like it’s a million miles away.”

And it is the national church’s leader, Archbishop Justin Welby of Canterbury, who is accused by many Telegraph readers who share fears about the future of their church.

Cluiver Miller suggests that Welby “must take a great deal of responsibility for destroying the Anglican Church with its virtue signaling and self-righteousness.” Incredibly uncommunicative.”

Another, Nigel Allen, urges the archbishop to “concentrate on day-to-day business rather than fighting government policy on illegal immigrants in the Lord”.

A widening gap between the priorities of the national leadership and what is happening in the neighborhoods can be seen even in places no more than a few kilometers from Lambeth Palace.

Like Greg Smith in Shropshire, the Rev Ruth Burge-Thomas, vicar of the Church of the Holy Spirit in Clapham since 2012, lives the daily struggle to make the Church relevant to her local community in 2024.

A local girl, whose mother grew up on one of the council estates in the neighbourhood, argues as a vicar: “You own the community. “Whenever I go out, a five-minute walk usually takes me 45 minutes because so many people stop me to talk about what’s bothering me.”

He reports that his regular congregation of around 40 people on Sundays will be on their feet at Easter, but believes church attendance can be as misleading as Church of England chapters making headlines.

“In my opinion, the Church is alive and thriving when it is outward-looking, feeding the hungry and comforting the bereaved. That’s the job that needs to be done, and that’s what we continue to do.”