Animal behavior research is based on careful observation of animals. Researchers can spend months in forest habitats watching tropical birds mate and raise their young. They can monitor physical contact rates in cattle herds of different densities. Or they could record the sounds whales make as they migrate through the ocean.

Animal behavior research can provide fundamental information about the natural processes that affect ecosystems around the world, as well as our own human minds and behaviors.

I study animal behavior as well as research reported by scientists in my field. One of the challenges of this kind of science is to ensure that our own assumptions do not influence what we think we see in animals. How scientists, like all people, see the world is shaped by biases and expectations, which can affect how data is recorded and reported. For example, scientists living in a society with strict gender roles for men and women may interpret what they see animals doing as reflecting the same distinctions.

The scientific process corrects such errors over time, but scientists have faster methods to minimize potential observer bias. Animal behaviorists do not always use these methods; But this situation is changing. A new study confirms that over the past decade, studies have increasingly adhered to best practices that can minimize potential bias in animal behavior research.

Prejudices and self-fulfilling prophecies

The German horse named Clever Hans is known in the history of animal behavior as a classic example of unconscious bias leading to wrong conclusions.

In the early 20th century, it was claimed that Clever Hans could do mathematics. For example, clever Hans would tap his hoof eight times in response to his owner’s command “3 + 5.” The owner would then reward him with his favorite vegetables. Early observers reported that the horse’s abilities were legitimate and that the owner was not deceptive.

However, careful analysis by a young scientist named Oskar Pfungst revealed that if the horse could not see its owner, it could not answer correctly. So even though Clever Hans wasn’t good at math, he was incredibly good at observing the subtle, unconscious clues that gave away his owner’s math answers.

In the 1960s, researchers asked human study participants to code the learning ability of mice. Participants were told that their mice had been artificially selected over many generations to be either “smart” or “boring” learners. Over several weeks, participants put their mice through eight different learning experiments.

In seven of eight experiments, human participants ranked “smart” mice as better learners than “dull” mice, when in fact the researchers had randomly selected mice from breeding colonies. Bias led human participants to see what they thought they should see.

Eliminate prejudice

Given the clear potential for human biases to skew scientific results, textbooks on animal behavior research methods from the 1980s onwards implored researchers to validate their studies using at least one of two commonsense methods.

The first is to ensure that the researcher observing the behavior does not know whether the subject is coming from one study group or another. For example, a researcher will measure the behavior of a cricket without knowing whether it comes from the experimental group or the control group.

Another best practice is to utilize a second researcher with fresh eyes and no knowledge of the data to observe behavior and code the data. For example, while analyzing a video file, I count the chickadees taking seeds from the feeder 15 times. A second independent observer then counts the same number.

However, these methods for minimizing possible biases are not often used by researchers in the field of animal behavior, perhaps because these best practices require more time and effort.

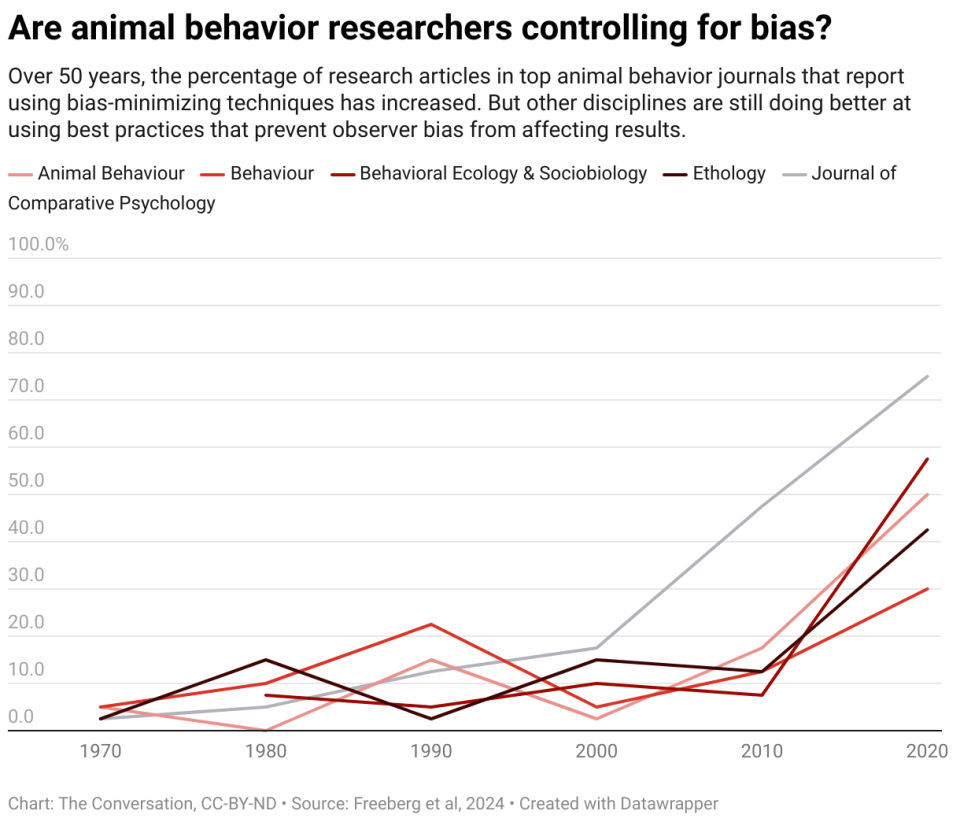

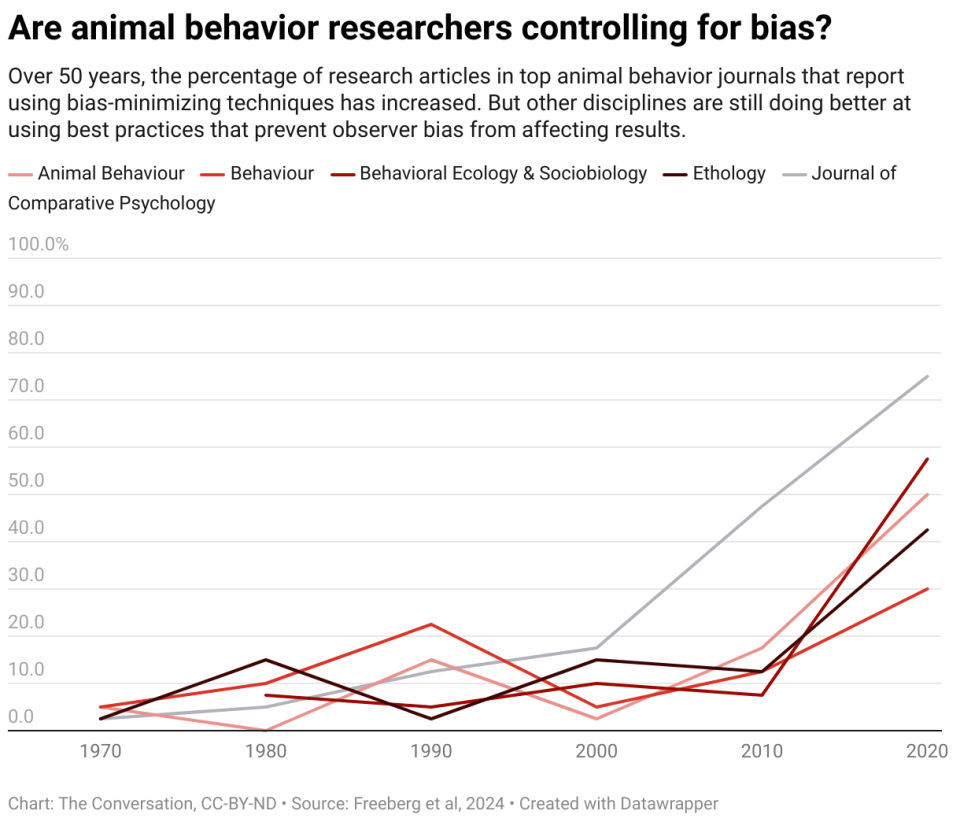

In 2012, my colleagues and I examined nearly 1,000 papers published in five leading animal behavior journals between 1970 and 2010 to see how many reported these methods to minimize potential bias. Less than 10 percent did so. By contrast, Infancy, a magazine focused on babies’ behavior, was much more rigorous: More than 80% of its articles reported using methods to avoid bias.

This is a problem that is not just limited to my field. A 2015 review of articles published in the life sciences field found that blinded protocols are rare. It also found that studies using blinded methods detected smaller differences between key observed groups than studies that did not use blinded methods, suggesting that potential biases lead to more notable results.

Our article was cited regularly in the years after we published it, and we wondered if there was any progress in this area. Therefore, we recently reviewed 40 articles from each of the same five journals for 2020.

We found that the proportion of articles reporting bias control increased across all five journals; The rate, which was below 10% in our 2012 article, increased to just over 50% in our new review. However, these reporting rates still lag behind Infancy magazine, which was at 95% in 2020.

All in all, things are getting better, but the field of animal behavior can still do better. Practically speaking, with increasingly portable and affordable audio and video recording technology, it is becoming easier to implement methods to minimize potential biases. The more the field of animal behavior adheres to these best practices, the stronger the foundation of knowledge and public confidence in this science will be.

This article is republished from The Conversation, an independent, nonprofit news organization providing facts and authoritative analysis to help you understand our complex world. Written by: Todd M. Freeberg, University of Tennessee

Read more:

Todd M. Freeberg does not work for, consult for, own shares in, or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond his academic duties.