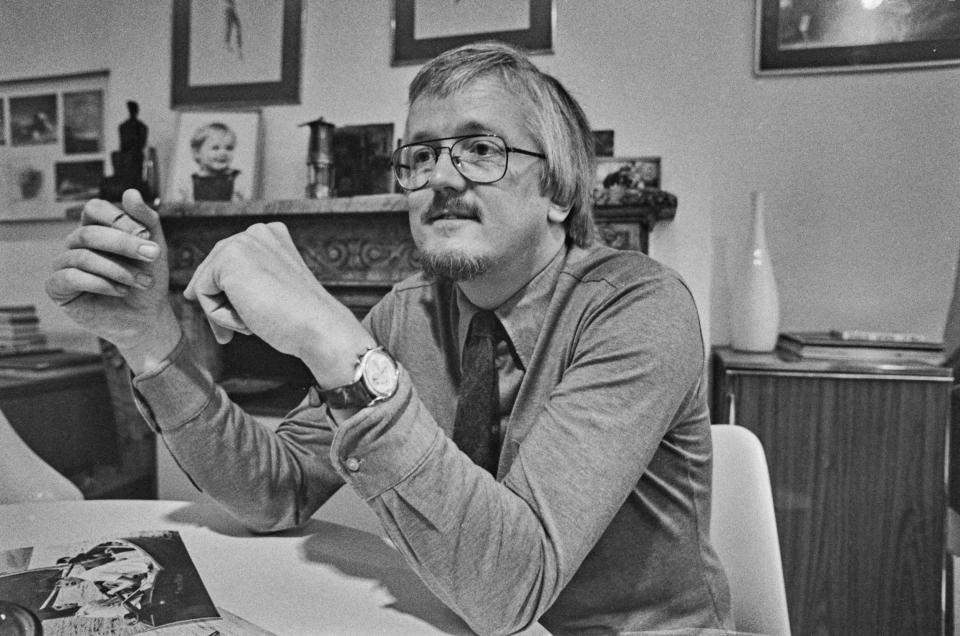

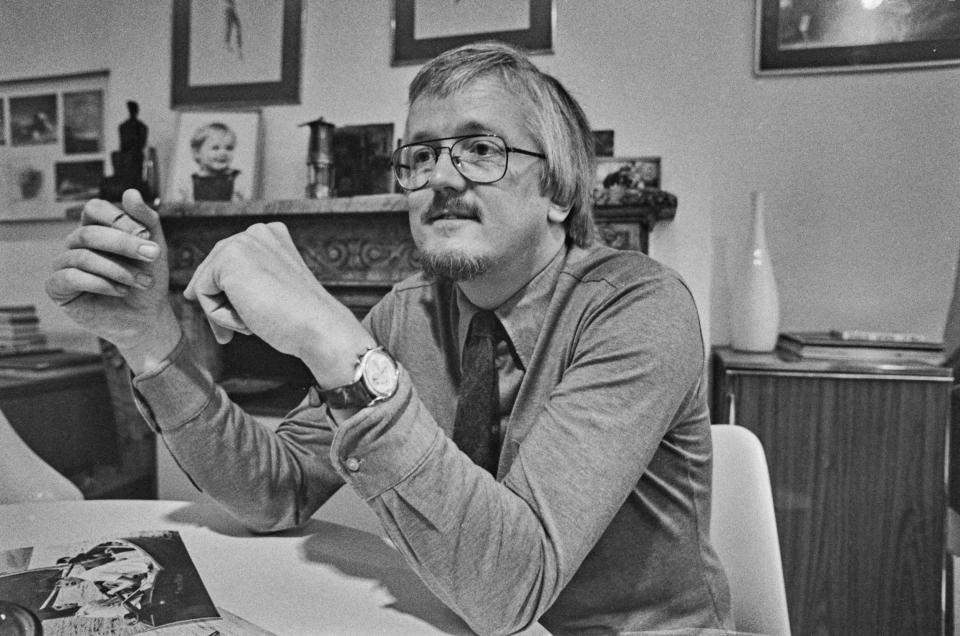

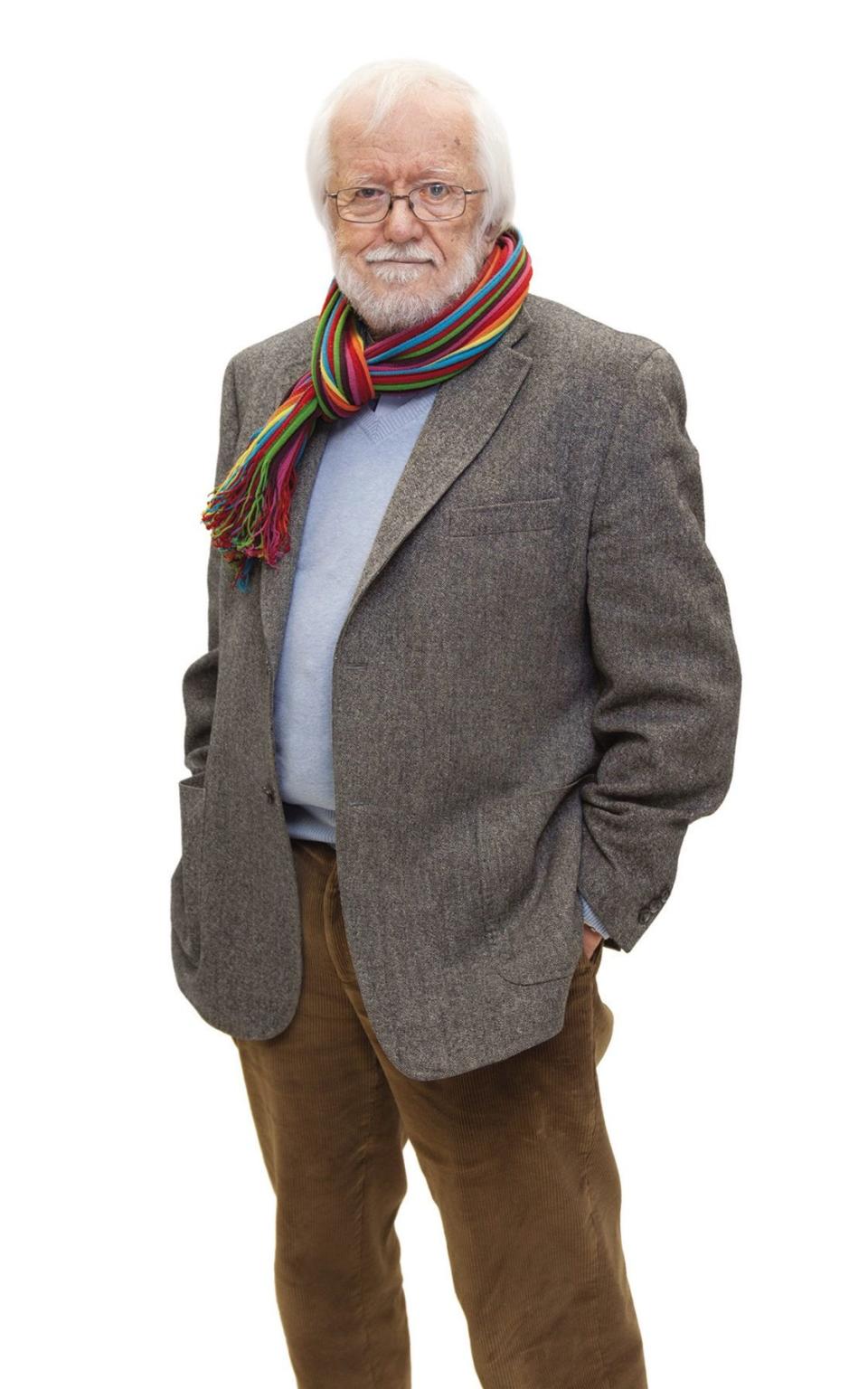

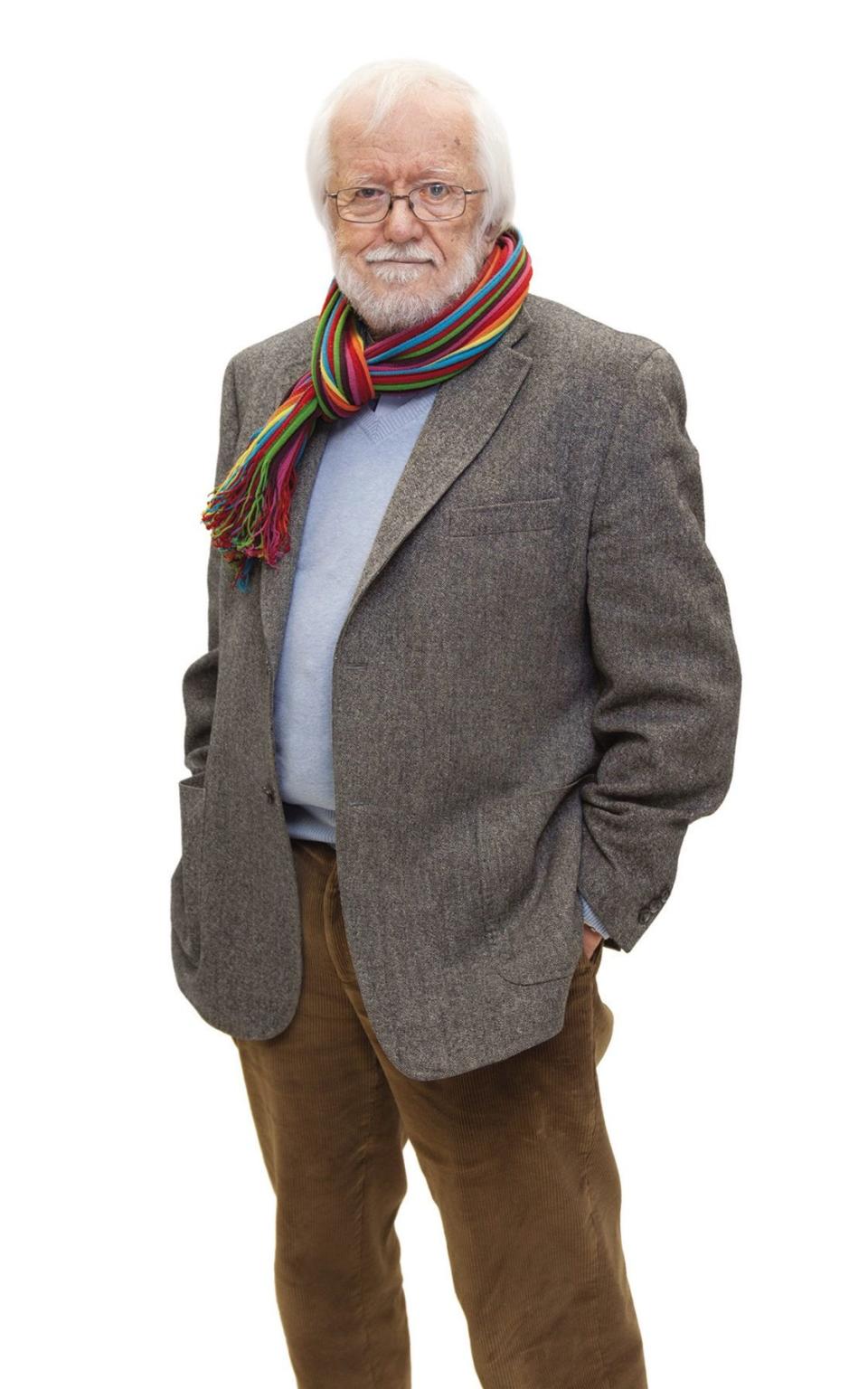

Richard Pilbrow, who has died aged 90, was the doyen of British theatrical lighting designers and one of the last survivors of the team assembled by Sir Laurence Olivier in the 1960s to design the new National Theater on the South Bank. He was also the author of the lighting designer’s bible, Stage Lighting (1970), nicknamed “The Old Testament,” and its revised 1997 edition, “The New Testament.”

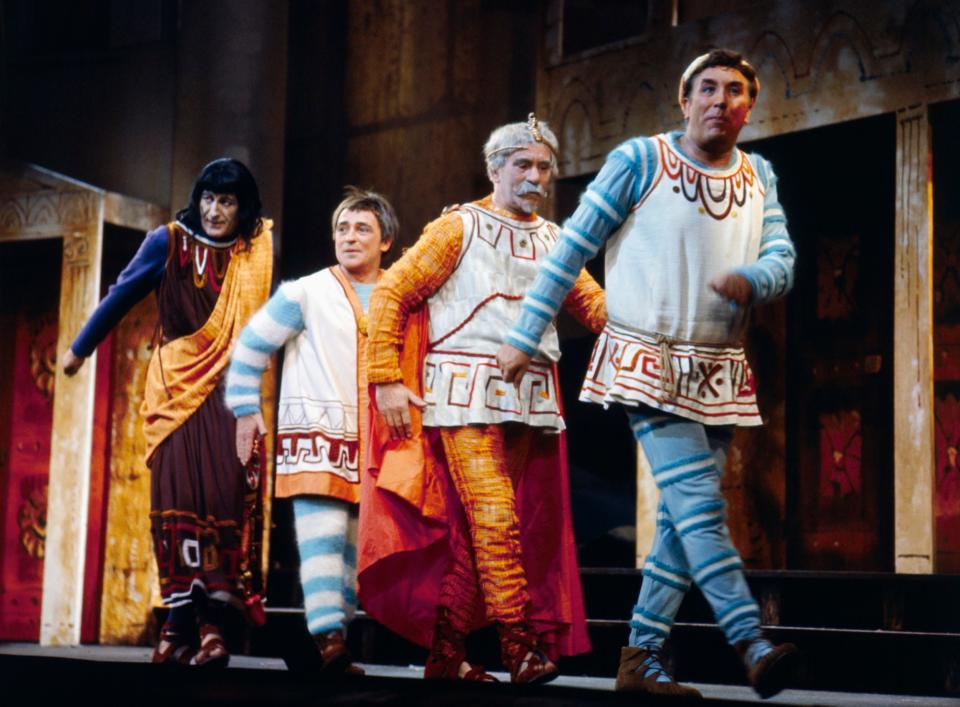

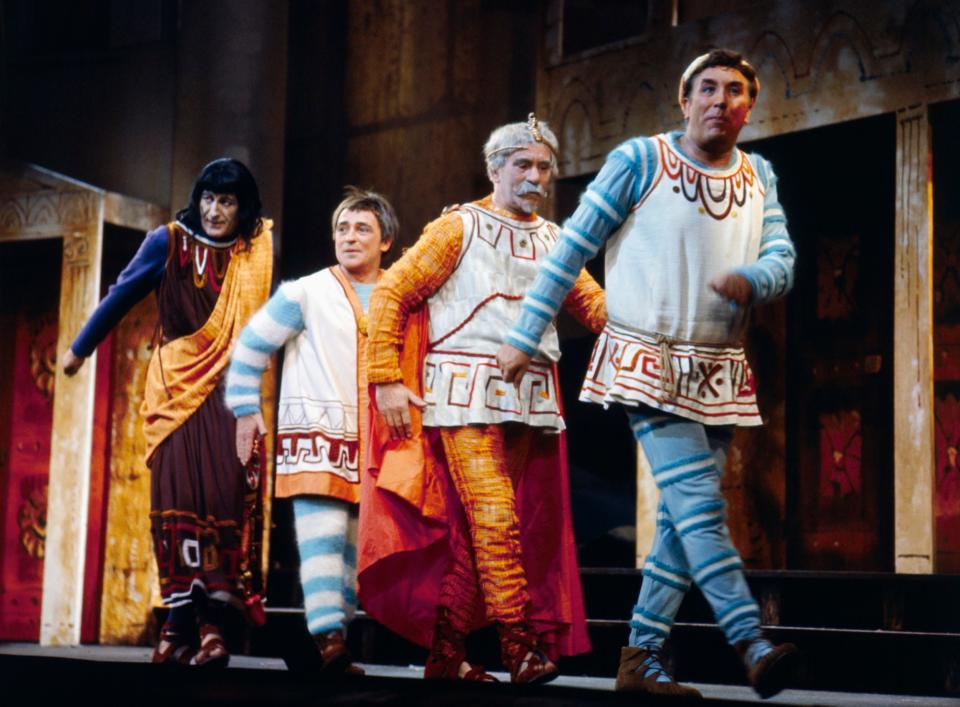

Pilbrow was one of the first generation of lighting designers to be considered artists rather than merely electricians. In the early 1960s, he had made a name for himself as a modernizer by pioneering the use of film projections on stage in the Peter Cook/Kenneth Williams revue One Over the Eight (1961) and the Broadway production of A Funny Thing Happened on the Eight. Road to the Forum (1962), which he later brought to the West End as co-producer.

In 1957 he had founded Theater Projects, Britain’s first theater consultancy, which started by renting lights salvaged from understage at Drury Lane, and would shape design as well as becoming Europe’s largest provider of theatrical light and sound. One of hundreds of theaters around the world. Stage called him “the Bill Gates of the theater world.”

Olivier employed Pilbrow as lighting designer, first at the Chichester Festival Theatre, and then in 1963 for the National Theater Company based at the Old Vic, where Peter O’Toole lit Hamlet (1963), Love for Love (1966). took. ) and Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead (1966). He clashed with O’Toole, who wanted Pilbrow fired, but Olivier was impressed; He likened his previous expertise in lighting displays to “flying ‘by the seat of our pants’ before and during the War” compared to Pilbrow’s, which was the equivalent of “required to handle today’s jumbo jets.”

Meanwhile, the pregnancy of the National Theatre’s permanent home on the South Bank was a painful one. Architect Denys Lasdun was appointed unanimously in 1963 (partly because he was the only candidate who did not come with a self-aggrandizing team) but relations subsequently degenerated into – as Lasdun put it – “a pretty good hell”.

In 1966 Pilbrow joined the National Theater Building Committee and found it to be a pyrotechnic mix of egos. “Theatre people”, including Olivier, William Gaskill, Peter Brook and Peter Hall, clashed with each other and with Lasdun, who was nearing resignation. No one could agree on what the huge new space (quickly divided into two auditoriums, the open stage Olivier and the proscenium arch Lyttelton) should look like.

![Denys Lasdun explains his 1965 (later abandoned) twin National Theater and Opera House proposal for 'a series of terraces' [cascading] to a central valley](https://s.yimg.com/ny/api/res/1.2/1y7.PUACB9pBayMCxHpyHA--/YXBwaWQ9aGlnaGxhbmRlcjt3PTk2MDtoPTk4MA--/https://media.zenfs.com/en/the_telegraph_818/ae25cf1d36d040c4c6e372e7a5224131)

![Denys Lasdun explains his 1965 (later abandoned) twin National Theater and Opera House proposal for 'a series of terraces' [cascading] to a central valley](https://s.yimg.com/ny/api/res/1.2/1y7.PUACB9pBayMCxHpyHA--/YXBwaWQ9aGlnaGxhbmRlcjt3PTk2MDtoPTk4MA--/https://media.zenfs.com/en/the_telegraph_818/ae25cf1d36d040c4c6e372e7a5224131)

“I was the only person backstage there,” Pilbrow later told Daniel Rosenthal, author of The National Theater Story. “Gradually Lasdun got into the habit of asking my opinion as to which of two opposing possibilities might be a little more practical.” Pilbrow traveled with Sir Laurence Olivier to various theaters in the West End to measure how far away, according to Olivier, the farthest audience member could sit. From these tests they determined the boundaries of the National Theatre’s two large theaters: 65 feet.

In 1967 Theater Projects were appointed as the National’s official stage and lighting consultants. Pilbrow’s most challenging task was to achieve success on the open stage of the Olivier Theatre.

In 1973, construction was ongoing and he was holidaying on the island of Coll with sound engineer David Collison. On the beach, they drew a life-size plan of the then-top-secret Olivier Theatre. (“Hopefully there won’t be a helicopter flying over with a camera on us,” Pilbrow said.) They were horrified when they saw it from the adjacent hill: “It was so wide” – 2.5 times the width of the Old Vic.

Pilbrow has developed an innovative rotary drum incorporating two semicircular elevators. Thanks to a fully computerized flight system of 127 cranes (albeit riddled with insects), it was the world’s first open stage, capable of accommodating almost any scenery imaginable. Lasdun was initially angry: “I am the architect, how dare you! Your ‘ears’ on my fly tower will change the skyline of my building and the skyline of London for all time!”

Pilbrow designed the more conventional Lyttelton (which he gloomily described as a giant Odeon cinema) so that all the sets could be transported in trolleys, which he likened to “big tea trays”.

After years of delays, Peter Hall, who replaced Olivier as NT director in 1973, ordered plays to begin being produced in theaters that had not yet been completed. Pilbrow needed to ensure there was a floor for the actors to stand on and electricity to turn on the lights. “Sophisticated computers were coming in for flight, light and sound in unplastered rooms,” he recalled.

Olivier and Lyttelton opened in 1976 but Pilbrow was never happy with either. “Brilliant theater people have overcome these challenging spaces, but my heart still aches for our National Theater to include more actor-friendly spaces,” he said.

He got his chance in 1973 when he was asked to give advice on the Cottesloe (now renamed Dorfman), which had a huge hole under Olivier’s backstage. Sketch design by Theater Projects newcomer Iain Mackintosh; His vision was for a courtyard that was simple in decoration but “filled with people on three levels” so that the audience would “complement the furniture the way wallpaper completes a room”. ”, as Mackintosh recalled.

Cottesloe opened in 1977 and inspired many imitators. It was a dazzling moment for Pilbrow, who continued the backlash against the fashion for huge, fan-shaped auditoriums that lasted from the 1930s to the 1970s, and instead revived the old-fashioned stacked balconies of 18th-century opera houses. To bring as much of the audience as possible closer to the actors.

“Tradition has held sincerity as the primary desirable characteristic of theatre, and the best are the miracles of compressed humanity,” he said. The mid-century “rules” of perfect sightlines, no old-fashioned boxes, and no balconies were “wrong.” “We had thrown away a rich tradition of theater design that, since the days of Shakespeare, had emphasized one fundamental thing: contact between actor and audience.”

Richard Pilbrow was born in Beckenham on 28 April 1933 to Olympic fencer Gordon and his music teacher wife Marjorie. He attended Bickley Hall preparatory school; here he spent hours collecting data on West End shows and appearances at Pollock’s Toy Theatre, then Cranbrook School. After serving as a corporal in the RAF, he studied stage management at the Central School of Speech and Drama.

After graduating in 1955, he began his theater career as assistant stage manager at Her Majesty’s; Two years later, she borrowed £60 from her father to set up Theater Projects Ltd with her assistant Bryan Kendall. She later made her name at Hammersmith Lyric with a string of hits in the late 1950s.

Broadway producer Harold Prince, with whom he brought A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Forum to London in 1963, asked him to handle the film projection aspect of the Broadway musical Golden Boy (1964), starring Sammy Davis Jr.. In 1968, with Zorba, Pilbrow became the first British lighting designer to be commissioned the entire lighting scheme for an original Broadway musical. He was one of the first British designers invited to United Scenic Artists and earned a Tony nomination, a Drama Desk award and an Outer Critics award for his lighting.

Meanwhile in the West End, in partnership with Prince, he produced Fiddler on the Roof with Topol, Cabaret with Judi Dench, and Stephen Sondheim’s Company and A Little Night Music, as well as working on Ian McKellen’s Edward II and Richard II, I . I’m Not Rappaport with Paul Scofield, Stooping to Conquer with Tom Courtenay, Peter Barnes’ Executive Class and the debacle of TWANG!

In the 1970s Pilbrow turned to films; produced Swallows and Amazons (1974), shot primarily in the Lake District; There was a minor scandal when it was revealed that a crew member had seduced local girls by claiming to be Richard Pilbrow.

Theater Projects nearly ran aground in the early 1980s, but Pilbrow survived by selling lighting services and continuing consultancy, which proved successful. As a theater consultant, Pilbrow shaped the Barbican, Manchester’s Royal Exchange Theater and Glyndebourne; Theater Projects has completed over 1,800 projects in 80 countries, including many major venues in the United States, where Pilbrow has lived since 1988.

He was a co-founder of the Association of Lighting Designers, the British Association of Theater Technicians, the British Institute of Theater Consultants and the British Association of Theater Designers. In 2011, he published his memoir titled A Theater Project. His latest book, A Sense of Theatre: The Untold Stories of the Creation of Britain’s National Theater will be published next year.

Richard Pilbrow first married Viki Brinton, his partner in the early days of Theater Projects, in 1958, with whom he had a son and a daughter; and secondly, lighting designer Molly Friedel, with whom she had another daughter in 1974.

Richard Pilbrow was born on April 28, 1933, died on December 6, 2023.