Human fear of sharks has deep roots. Written works and works of art from the ancient world, B.C. It contains references to sharks that preyed on sailors from the eighth century onwards.

Stories about shark encounters transmitted back to land were embellished and amplified. Coupled with the fact that sharks occasionally (very rarely) bite humans, humans have been primed to imagine terrifying situations at sea for centuries.

in 1974 Peter Benchley‘s bestselling novel “Jaws” turned this fear into a wildfire that spread all over the world. The book sold over 5 million copies in the United States within a year, and was quickly followed by Steven Spielberg’s 1975 film, which became the highest-grossing film in history at the time. Virtually all audiences have embraced the idea, vividly depicted in the film and its sequels, that sharks are malevolent, vengeful creatures that prowl coastal waters and attempt to feed on unsuspecting swimmers.

But “Jaws” also sparked widespread interest in better understanding sharks.

Previously, shark research was largely the esoteric province of a handful of academic experts. Thanks to the attention generated by “Jaws,” we now know that there are many more species of sharks than scientists were aware of in 1974, and that sharks do much more interesting things than researchers realized. Benchley has become an enthusiastic spokesperson for shark conservation and marine conservation.

During my 30-year career studying sharks and their close relatives, rays and stingrays, I have seen attitudes evolve and interest in understanding sharks grow tremendously. Here’s how things have changed.

Swimming towards the spotlight

Before the mid-1970s, most of what was known about sharks came from people going to the sea. In 1958, to reduce wartime risks to sailors stranded at sea when their ships sank, the U.S. Navy created the International Shark Attack File, the world’s only comprehensive database of all scientifically documented, known shark attacks.

Today, the file is managed by the Florida Museum of Natural History and the American Elasmobranch Society, a professional organization for shark researchers. He works to inform the public about shark-human interactions and ways to reduce the risk of shark bites.

In 1962, Jack Casey, a pioneer of modern shark research, launched the Cooperative Shark Tagging Program. This initiative, which still continues today, relied on Atlantic commercial fishermen reporting and returning tags they found on sharks; so government scientists were able to calculate how far the sharks moved after they were tagged.

In the wake of “Jaws,” shark research quickly became mainstream. The American Elasmobranch Society was founded in 1982. Graduate students lined up to study shark behavior, and the number of published shark studies skyrocketed.

Field research on sharks has expanded in parallel with the increasing interest in extreme nature sports such as surfing, parasailing and scuba diving. Electronic tags allowed researchers to track the sharks’ movements in real time. DNA sequencing technologies have provided cost-effective ways to determine how different species are related to each other, what they eat, and how populations are structured.

This interest also had a sensational side, embodied in the Discovery Channel’s launch of Shark Week in 1988. Ostensibly designed to educate the public about shark biology and counteract negative publicity about sharks, this annual programming block was a commercial venture that exploited the tension between people’s deep-seated fear of sharks and their longing to understand what makes these animals tick.

Shark Week featured made-for-TV stories focusing on fictional scientific research projects. It was extremely successful and remains so today, despite criticism from some researchers who say it is a significant source of misinformation about sharks and shark science.

Physical, social and genetic information

Contrary to the long-held view that sharks are mindless killers, they display a wide range of characteristics and behaviors. For example, the velvet-bellied lantern shark communicates through flashes of light from organs on the sides of its body. Female hammerhead sharks can clone perfect copies of themselves without male sperm.

Sharks have the most sensitive electrical detectors ever discovered in the natural world; The networks of pores and nerves on their heads are known as the ampoule of Lorenzini, after Stefano Lorenzini, the Italian scientist who first described these features in the 17th century. Sharks use these networks to navigate the open ocean using the Earth’s magnetic field for orientation.

Another intriguing discovery is that some shark species, including mako and blue sharks, are separated by both sex and size. Among these species, cohorts of males and females of different sizes are often found in distinct groups. This finding suggests that some sharks may have social hierarchies similar to those seen in some primates and hoofed mammals.

Genetic studies have helped researchers explore questions such as why some sharks have hammer- or spade-shaped heads. They also show that sharks have the lowest mutation rate among vertebrate animals. This is notable because mutations are the raw material of evolution: the higher the mutation rate, the better a species can adapt to environmental change.

But sharks have existed for 400 million years and are experiencing some of the most extreme environmental changes on Earth. It is not yet known how they have survived so successfully with such a low mutation rate.

Marquee types

White sharks, the focal species of “Jaws,” attract great public attention, although much is still unknown about them. They can live to be 70 years old and regularly swim thousands of kilometers each year. Those in the western North Atlantic tend to move north-south between Canada and the Gulf of Mexico; White sharks off the west coast of the United States move east-west between California and the central Pacific.

We now know that juvenile white sharks feed almost exclusively on fish and rays, and that they do not begin to include seals and other marine mammals in their diet until they are the equivalent of juveniles and reach a length of about 12 feet. Most confirmed white shark bites on humans appear to be carried out by animals between 12 and 15 feet long. This supports the theory that nearly all bites of white sharks on humans are cases of mistaken identity, in which the humans resemble the seals the sharks prey on.

still in water

Although “Jaws” has had a broad cultural impact, it hasn’t stopped surfers and swimmers from enjoying the ocean.

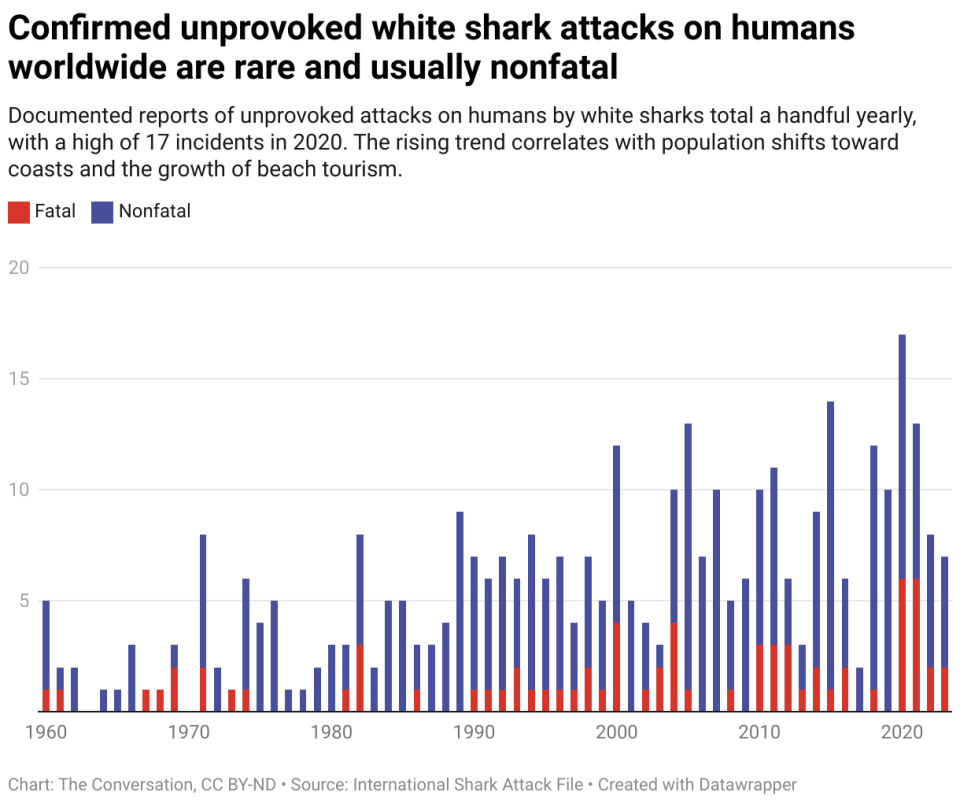

Data from the International Shark Attack File on confirmed unprovoked bites by white sharks from the 1960s to the present show a steady increase, although the annual number of incidents remains quite low. This pattern is consistent with increasing numbers of people engaging in recreational activities on the coasts.

There have been 363 confirmed, unprovoked bites by white sharks worldwide since 1960. 73 of these were fatal. The World Health Organization estimates there are 236,000 drowning deaths per year; This translates to approximately 15 million drowning deaths during the same period.

In other words, people are approximately 200,000 times more likely to drown than to die from a white shark bite. Indeed, surfers are more likely to die in a car accident on their way to the beach than to be bitten by a shark.

This article is republished from The Conversation, an independent, nonprofit news organization providing facts and analysis to help you understand our complex world.

Written by Gavin Naylor university of florida.

Read more:

Gavin Naylor receives funding from the National Science Foundation and the Lenfest Foundation.