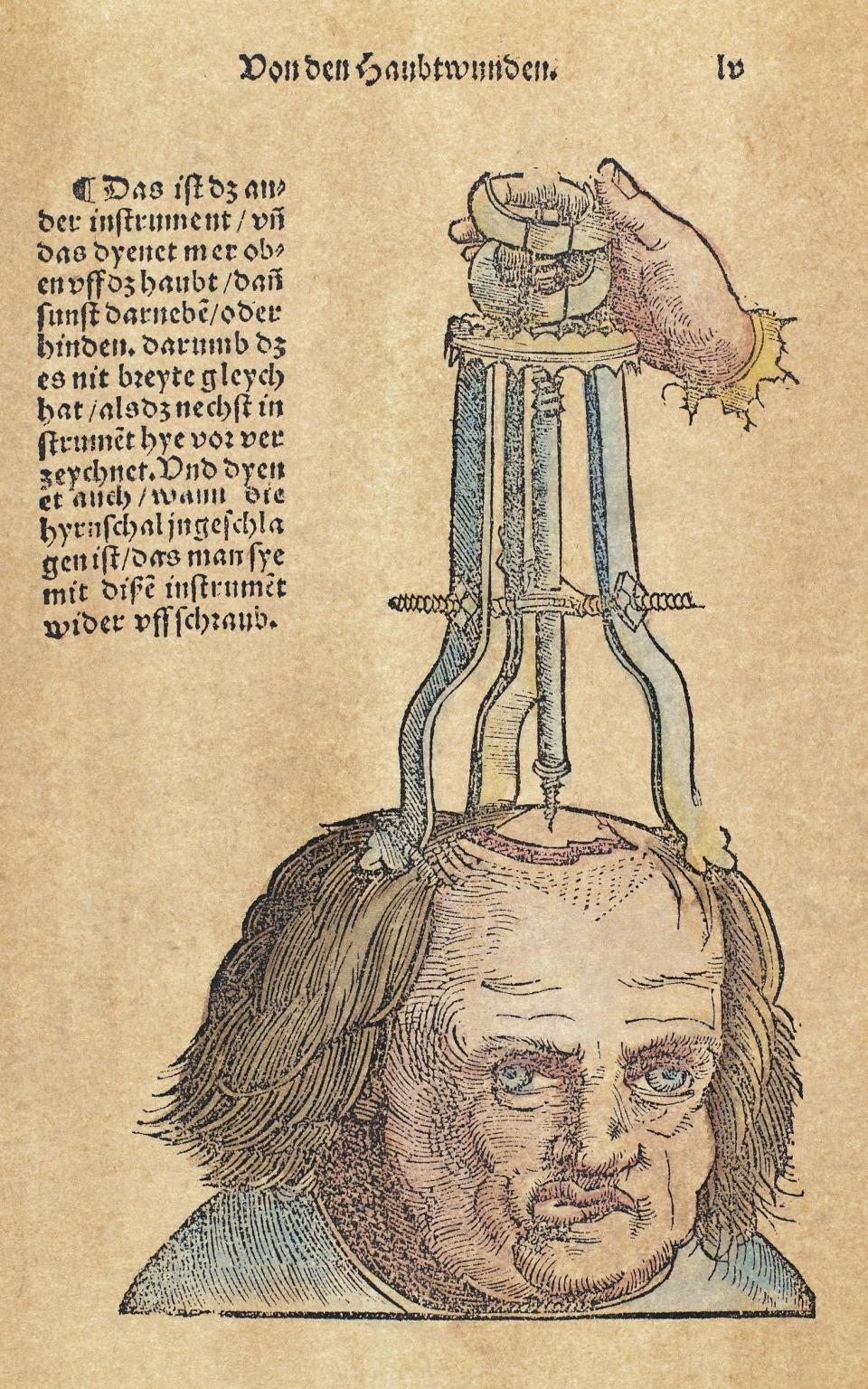

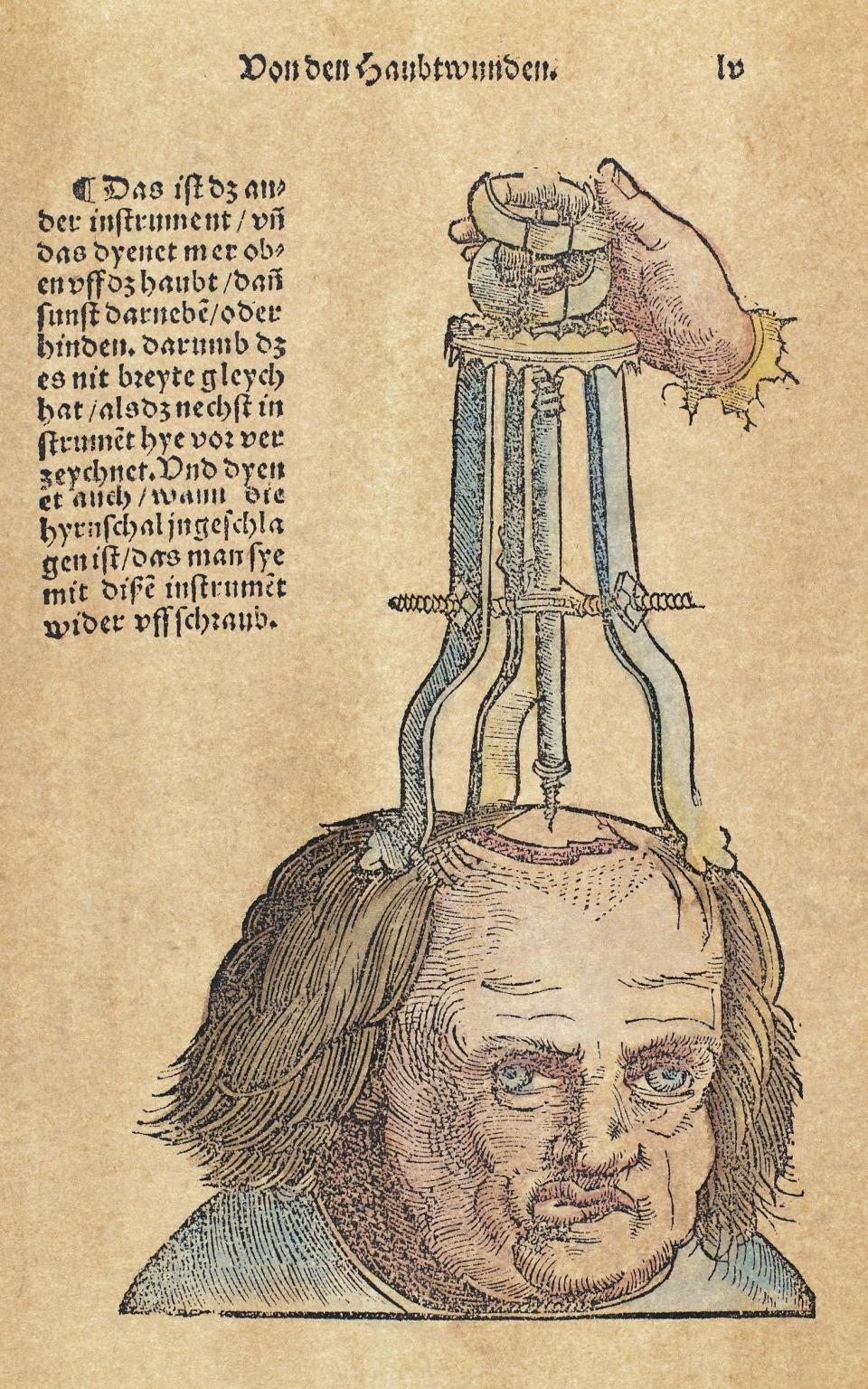

Throughout history, attempts by ordinary mortals to destroy the inner recesses of the soul have been viewed as arrogant. Shakespeare had Hamlet express this powerfully when he was angry at those who would “pluck out the heart of my mystery.” He accuses Rosencrantz and Guildenstern of trying to play him like some kind of instrument instead of treating him like a human being. “What a worthless person you make of me,” he scolded.

There are no such taboos today. Hamlet refers to himself figuratively as “this little organ,” but now we take the self apart by examining the brain, which is literally an organ. Neuroscientists are disproving the long-held view that what lies deep down can only be seen from the inside.

At the Francis Crick Institute, with the lively title Hello Brain! A new exhibition titled Celebrates this desecration of the soul’s inner sanctuary and reveals how the institute’s researchers have opened the lid on the mind.

Crick’s researchers found that the brains of mice change during pregnancy; This suggests that the maternal instinct is not just a spiritual call but also a neurochemical imperative. Another lab’s study on mice supports the emerging scientific consensus that we hallucinate more than we think. Other Crick scientists have studied how birds learn new songs in their sleep and suggested that the unconscious mind is more important for learning and memory consolidation than we realize.

It’s absolutely fascinating, but don’t be surprised by the cheerful tone in which the exhibition presents such explorations. As mobster Henry Hill said in Goodfellas, “Your killers come smiling.” These wonderful explanations threaten to destroy precious beliefs about who and what we are. Call it the existential brain drain: The more we understand the brain, the more our comforting views of ourselves become wasted.

Our age-old (and some might say naive) understanding of human nature has long been based on three dogmas. The first is that we are the creators of our own choices and actions. We are not puppets, we are responsible, free actors who can make our own way in the world. The second is that humans are special beings, different from other animals. Third, we assume, at least most of the time, that our perceptions accurately represent the world as it is.

Scientific study of consciousness has cast doubt on all three of these beliefs. Take away our free will. It should surprise no one to discover that mothers’ brains change during pregnancy. Attributing our moods and behaviors to hormones has become the new common sense. But the idea that our thoughts and actions are the direct result of brain activity can also be disturbing. If “my brain made me do this”, in what sense can I control myself?

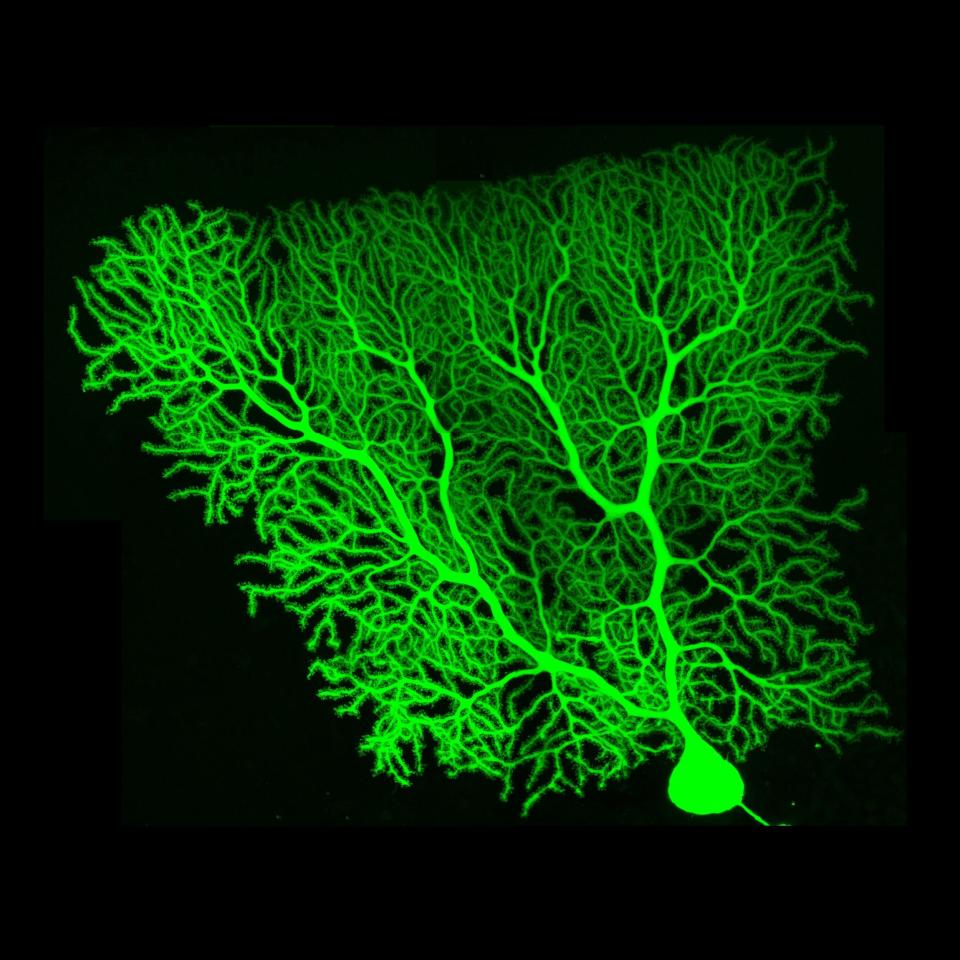

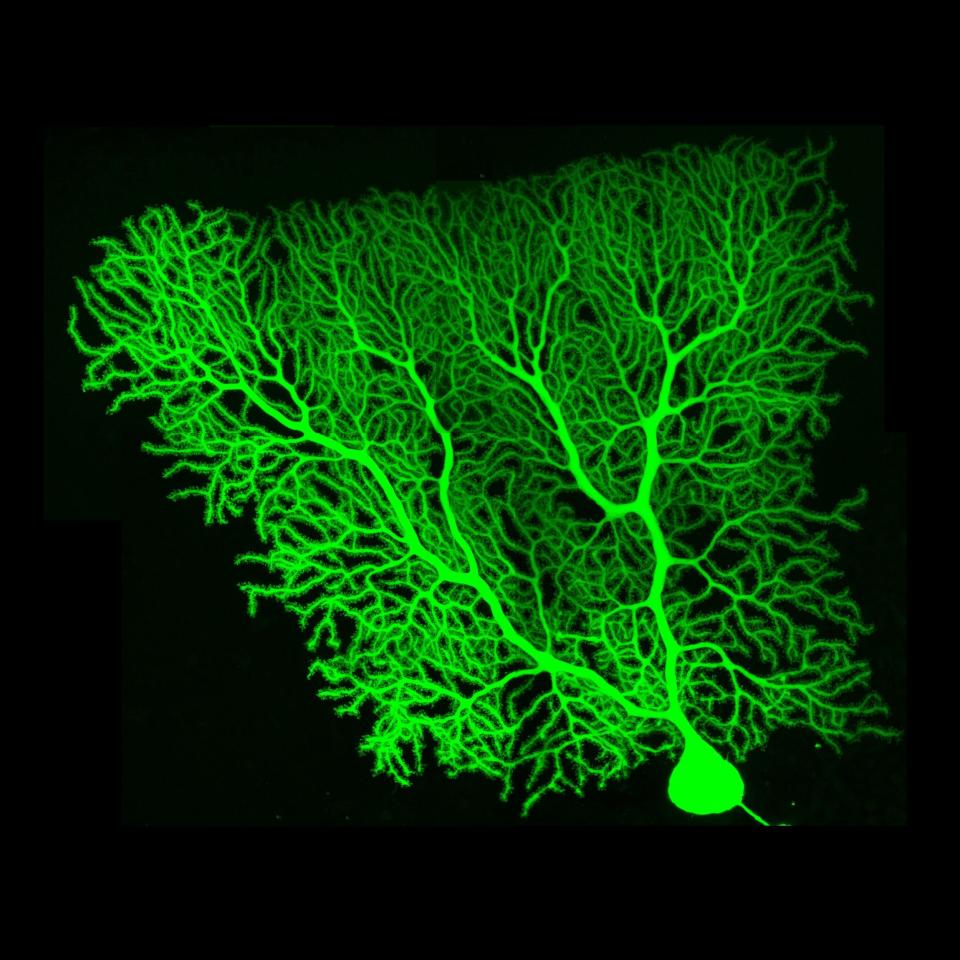

Much of Crick’s research seems to suggest that the brain is a kind of machine and that we are simply following its orders. One lab creates cell-by-cell models of brain circuits as if they were a giant arrangement of microscopic Lego pieces. Another team created a complete map of a fruit fly’s brain; This proved that we might one day be able to do the same thing for our own complex circuits. Crick’s research on Alzheimer’s disease is a reminder that our cognitive capacities are entirely dependent on healthy, functioning brains, and when they are impaired, we are impaired, too.

The fact that much of the research mentioned above is based on studies of birds, mice, and flies suggests that, beyond the need to insulate humans from experimental health risks, we do not embrace the idea that humans are fundamentally different from other animals. seriously now. We study animal brains because they tell us things about the human brain. But if the gap between humans and other animals is narrowing, does that mean we should value human life less or respect the lives of other creatures more? In both cases, the genre hierarchy on which we build our moral universe is problematic.

Perhaps most disturbing is our inability to perceive the world as it is. We have known for centuries that our senses, not objects, determine how the world appears to us. For example, the green of grass is produced by our visual system. But newer research goes further. Our brains don’t just color our perceptions (sometimes literally), they actually construct them. Brains are not passive receptors of perception, but “prediction machines” that see what they expect to see and hear what they expect to hear.

Think of it this way. We tend to think of our minds as video cameras recording the world. In fact, they are more like projectors that create our reality. Of course there is incoming data. But this data is used to help train the projector to get better and flag when the projection doesn’t include something critical. Therefore, we often fail to notice things that are not directly related to our survival, such as the features of the buildings we pass every day.

Such studies provide a better understanding of psychosis and a convincing conclusion that people who hear voices are not so different from others. We all have voices in our heads. One emerging theory is that the only difference is that some people sense that these voices are coming from someone outside themselves. This mistake is all too understandable. If we mostly perceive reflections of the brain, all that has to happen is that the brain reflects the wrong thing and we perceive things that are not there.

Collectively, findings like these reduce the size of the concept of consciousness. Consciousness is often thought of as the highest state of being, what makes us superior to ordinary animals. To thinkers such as 17th-century French philosopher René Descartes, our consciousness implied that we were immortal, indivisible, immaterial souls. We are not our bodies, but our minds with a singular and unified view of the world.

The image of the mind that science offers us today, and with it the image of the self, is much more complex. We are not immaterial spirits, we are physical animals whose brains do most of the thinking. Moreover, these brains are not simple, unified centers of experience. They carry out all kinds of processes in parallel. Often the problem is not just that the left side doesn’t know what the right side is doing: all kinds of things are going on without any of it coming to conscious awareness.

Putting all this together, we might worry about what will come of Crick’s cheerful invitation to say Hello, Brain. It is also that we will have to say “goodbye to myself”. Brain science has shattered our illusions and we now have to accept that we are nothing more than biological machines, perhaps more advanced than mice, rats and birds, but still just another animal.

But while humanity could benefit from a dose of humility, it would be a mistake to conclude that science has deprived us of everything we value. There is a tendency to interpret scientific discoveries about fundamental elements of human nature as meaning that we are “no more” or “merely” than the basic physical processes that science has revealed. But it is a philosophical mistake to believe that the only things that are real are the things you find at the most basic physical level. For example, when you break down a piece of music, you find nothing more than a series of sounds. But the sounds that collectively make up Beethoven’s last quartets have a completely different quality than the sounds that make up the sound of the M25 during weekday rush hour.

Likewise, when we look inside the brain, we find neurons firing, blood pumping, circulating hormones. But what they reveal remains truly remarkable. The fact that you can read and understand ideas like this shows how wrong it is to say that you are “just” some kind of biological computer.

Therefore, we should not worry that there is no fundamental distinction between us and the rest of the animal kingdom. Of course, our similarities mean that we must not be indifferent to their welfare and put an end to cruel agricultural practices. But just because all animals owe their existence to the same basic biological processes does not mean that they are all fundamentally the same. After all, only we humans have ever been able to direct our lives on any basis other than inherited instincts. We can choose not to reproduce, not to eat what our ancestors ate, to adopt lifestyles that other members of our species would not even consider.

This is possible because although many other creatures are conscious, our awareness of our own consciousness is unique. We can reflect on what we perceive, question our motives, and even examine our own brains.

The worry that we do not perceive the world in itself is unfounded. While it is true that much of what we perceive is a form of projection, we would not survive for long if it were not generally true. A creature that actually reflected a flat area with a cliff edge would not survive to pass on its genes. Even the colors, textures, smells, and sounds we give the world must somehow correspond to how it actually is. For example, whether a stick of butter tastes delicious or rancid tells us something about its freshness.

Whether we have free will remains perhaps the most difficult and troubling question that emerges from science’s study of the mind. If by “free will” we mean a quasi-magical power that produces choices independently of our brain and bodily processes, we simply do not have it. If we simply mean the capacity to make choices for ourselves, we clearly do so. The “me” that merely makes the choice is a complex biological system without a central controller.

This can be a difficult concept to grasp, as we are so seduced by the idea of a simple, singular inner self, separate from the body. For example, the phrase “my brain made me do this” assumes that there is a difference between “me” and “my brain.” But your brain is not only a part of you, it is the most important part. We should not worry but be glad that our brain plays the main role in determining what we do, because if it didn’t, what else would it do?

There is much about human consciousness that remains mysterious and unexplored. But it is time for us to lose Hamlet’s fear that revealing his secrets would threaten our humanity. You’ll leave Crick’s exhibit as a remarkable creature as the one that walked in, but with the added benefit of understanding a little better why you’re so amazing. And it is precisely our ability to see ourselves from the outside that makes us humans so unique.

Hello Brain! 2 March to 7 December at the Francis Crick Institute, London NW1 (crick.ac.uk); Julian Baggini’s latest book is Thinking Like a Philosopher (Granta, £10.99)