General Thomas Stafford, who has died aged 93, was not one of the 12 astronauts to walk on the Moon; but as commander of Apollo 10 in May 1969, he played a pivotal role in the dress rehearsal for the Moon landing. It approached within nine miles (14 km) of the lunar surface, paving the way for Apollo 11 two months later.

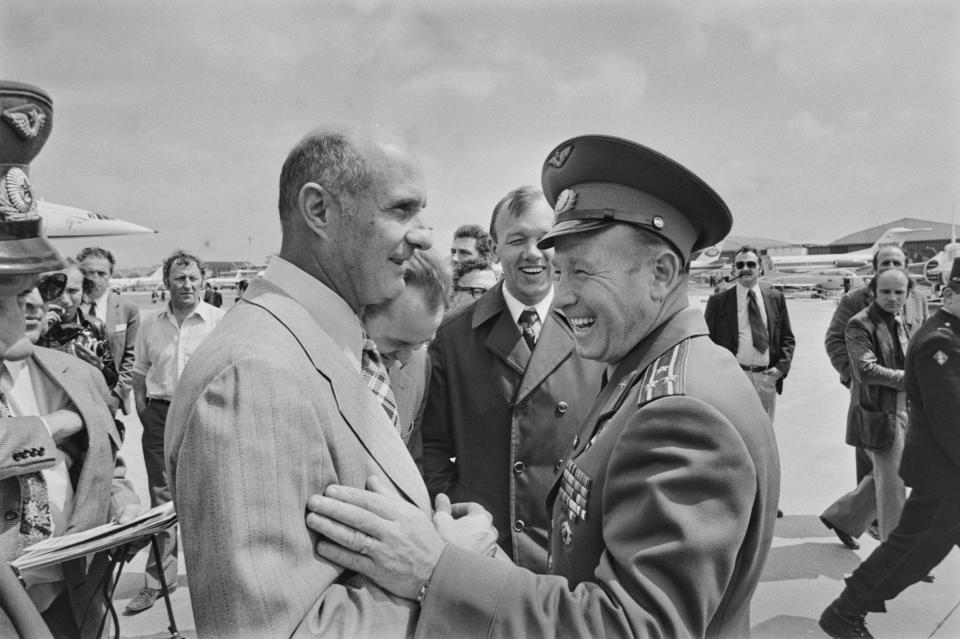

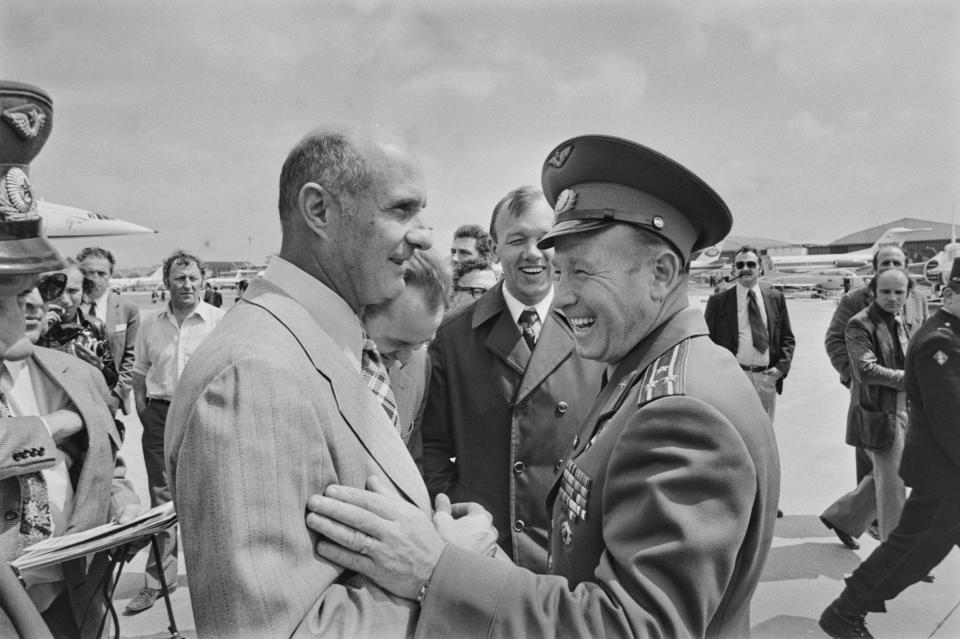

He also commanded the first Soviet-American contact in space in July 1975, which began the thaw in the 30-year Cold War between the two superpowers. To match the rank of Gen. Alexei Leonov, the colorful cosmonaut who commanded the two-man Soyuz spacecraft on which Stafford docked the three-man Apollo, Stafford was made a brigadier general (one-star) general, the first astronaut to reach that rank. high rank, high position.

The two commanders glided toward each other in the docking tunnel between Apollo and Soyuz, culminating in an awkward bear hug and handshake; this was the first international handshake in space. Leonov said in English: “It’s so good to see you!” Stafford expressed the same sentiment in Russian, but with such a broad Oklahoma accent that Leonov later said three languages were spoken at the mission: Russian, English and “Oklahomski.”

NASA had calculated that the symbolic handshake would take place over Bognor Regis, but the delay meant it would take place over the French city of Metz instead.

Along with the three years of planning, the flight itself was fraught with political jealousies and rivalries, and it was only the warm personal friendship that developed between the two commanders that saved it. As it happened, over the course of three days when the two vehicles docked or maneuvered at an altitude of 125 miles (200 km) above Earth, America’s Apollo presented the world with spectacular images of the Soyuz, but the Russians offered none of the Apollo. They said it was camera problems.

As a result, the Soviet people gained the impression that the Russians were in control; whereas it was the much more capable Apollo spacecraft with larger fuel reserves that performed most of the docking and maneuvering. But mutual respect between astronauts and cosmonauts gradually overcame national differences, and 30 years later the US-led international space station could not survive without Russian support.

Thomas Patten Stafford was born on September 17, 1930, in Weatherford, Oklahoma, and graduated cum laude from the U.S. Naval Academy in Annapolis in 1952 with a doctorate in law, science, and humane letters. He was commissioned into the U.S. Air Force and assigned to Hahn Air Base, Germany, in 1955; where he flew F86 fighter jets and co-wrote flight test manuals for pilots.

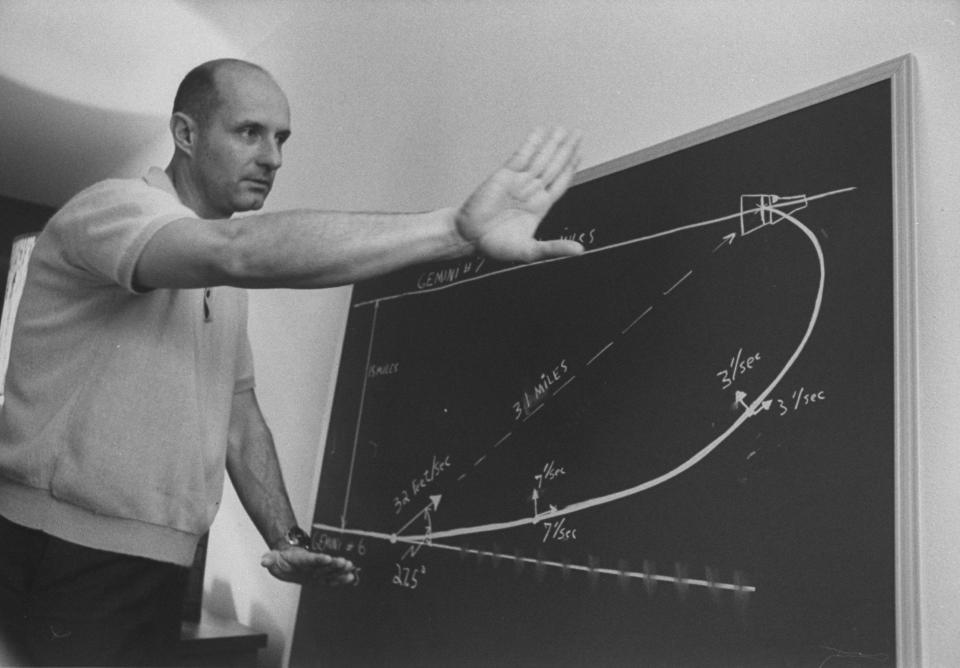

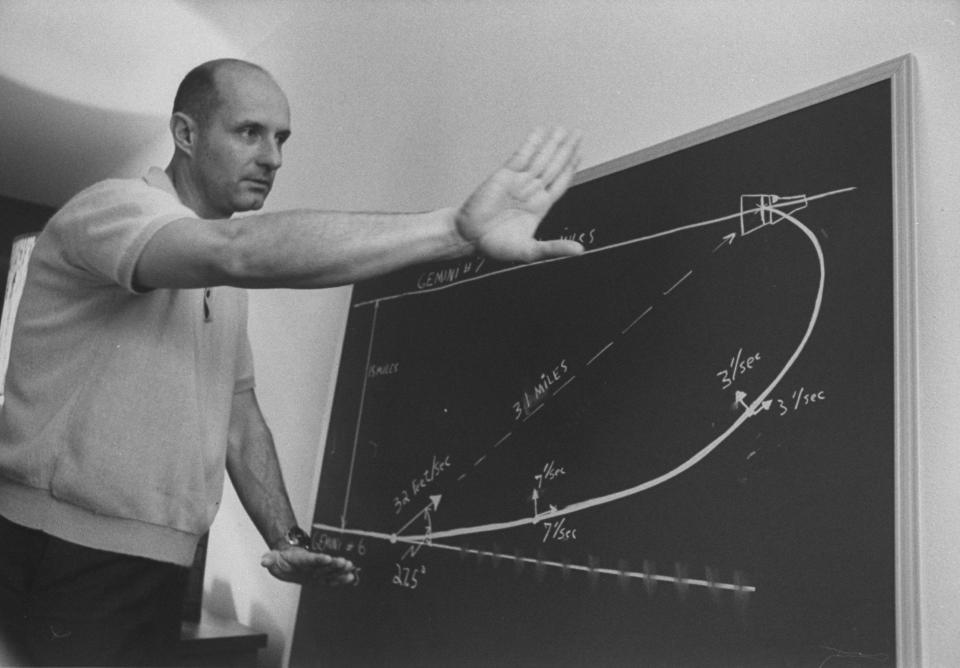

In 1962, he was selected for NASA’s second group of promising astronauts and flew the first two of four space flights during a series of 10 Gemini missions; this was a two-person spacecraft in which the instruments played a leading role in learning orbital rendezvous techniques. approaching space.

Unlike those on previous single-person Mercury flights, Gemini astronauts had computers that allowed them to control and maneuver independently of ground control. Backup commander Stafford was forced to take over the second of these flights, Gemini 9, after the main crew died in an air crash.

Stafford’s crew member Gene Cernan made history with a two-hour spacewalk, and new controls allowed the duo to splash down just half a mile (or less than a kilometer) from the rescue ship. Stafford later headed mission planning and software development for Project Apollo and played a leading role in organizing a series of missions that made the final moon landings possible.

Stafford, who commanded Apollo 10 during the final rehearsal, separated from Apollo and flew the lunar module with Cernan nearly to the surface of the Moon, returning eight hours later to perform the first docking with the main spacecraft into lunar orbit. Since they didn’t have enough fuel to take off again, there was no temptation for them to land. During their return, with John Young piloting the Apollo, the spacecraft reached 24,791 statute miles per hour; This was the fastest speed ever achieved by Man.

Following the Moon landing, Stafford was appointed head of astronauts responsible for the training and selection of flight crews. In this capacity he played an important role in plans for a joint Soviet-US flight.

This was part of the agreement on the peaceful exploration of space made by President Nixon and Soviet premier Alexei Kosygin in May 1972. This agreement, favorable to both superpowers, bridged the gap between the end of the Moon race and subsequent developments in space exploration. .

The two crews were selected and announced two years before the 1975 flight date, when Russia first named cosmonauts before they flew. Since experience was required as well as diplomacy, both countries chose veterans: Tom Stafford for the United States, Deke Slayton, the only one of the original seven astronauts who had never flown, and Vance Brand, who had many years of support experience. General Leonov, who made the world’s first spacewalk and established his own power base in Russia, was appointed commander of Soyuz with the support of Valeri Kubasov.

The first shock for the Americans was that they would dock not with the Salyut space station, as expected, but directly with the Soyuz spacecraft, so the opportunity to penetrate Soviet space secrets was much less. Many thought the docking would never happen, especially when Tom Stafford told the Russians who had blocked his request to go to Baikonur in Kazakhstan to inspect the Soyuz that the mission should be aborted.

This alarmed NASA bosses because 4,000 jobs were tied to the mission. But the Soviets also needed to move forward, and the next day Leonov put his arm around Stafford and said: “What’s the matter? Of course you can go to Baikonur.”

The Soviets then produced the first press kit—204 pages long, twice the size of NASA’s—and the simultaneous countdown began for the spacecraft, which were 10,000 miles (16,000 km) apart. Despite his surprise when Deke Slayton told a press conference that the Soviets had a “bad political system” and that he wanted no part of it, the two-day stand-off finally took place.

However, there was little confusion when Leonov chastised Soviet Mission Control for their impatience and told them: “We are preparing to receive our guests.” President Ford spoke to all five spacemen, but Brezhnev’s congratulations had to be read by a Soviet television news anchor.

A talented artist, Leonov eased political strife by drawing caricatures of American astronauts and showing them to cameras (including the bald Stafford, who looked as if he had hair), and the friendships they forged played a major role. What followed was a gradual thaw in East-West relations.

But for Nasa, celebrations at the end of a successful mission were marred by a mishap during reentry when exhausted American astronauts failed to operate some switches correctly, resulting in toxic gases being sucked into the spacecraft. All three developed blisters on their lungs and were hospitalized in Honolulu for two weeks.

When he left NASA in 1975, Stafford began a new and varied career, assuming command of the USAF Flight Test Center in Edwards, California, with the rank of major general. Three years later, he was promoted to lieutenant general and posted to USAF headquarters in Washington, D.C., as deputy chief of staff, research and development.

There he initiated work on the technology that led to the F117A stealth fighter jet and the revolutionary B2 stealth bomber, and served as a defense advisor to President Reagan. By 1990, he was chairing a committee advising on how to realize President George H. W. Bush’s vision of a return to the Moon and subsequent exploration of Mars, the so-called “road map” for the US’s subsequent 30-year human spaceflight program. .

When this work was completed under the Clinton Administration in 1994, Stafford co-founded a technical consulting firm and became a director of six companies, including the world’s largest hard disk drive manufacturer. He also served on various NASA boards and advised on problems ranging from the Hubble space telescope to the space shuttle and international space station.

Thomas Stafford was the recipient of many awards, and the airport in his hometown of Weatherford, Oklahoma is named after him.

Stafford had two daughters with his first wife, the former Faye L Shoemaker. He later married the former Linda Ann Dishman of Oklahoma, with whom he had two sons.

Thomas Stafford was born on September 17, 1930, died on March 18, 2024.