Flow, or “being in the zone,” is a state of increased creativity, increased productivity, and happy consciousness that some psychologists believe is the secret to happiness. It is considered the brain’s fast track to success in business, art or any other field.

But to achieve flow, one must first develop a strong foundation of expertise in their craft. That’s according to a new neuroimaging study from Drexel University’s Creativity Research Lab, which recruited Philly-area jazz guitarists to better understand the basic brain processes underlying flow. The research found that once mastery is achieved, this knowledge must be released and not overthought so that flow can be achieved.

As the senior author of this study, a cognitive neuroscientist and college writing instructor, we are a husband-and-wife team collaborating on a book about the science of creative insight. We believe this new neuroscience research reveals practical strategies to not only explain but also enhance innovative thinking.

Jazz musicians in flow

The concept of flow has fascinated creative people since pioneering psychological scientist Mihály Csíkszentmihályi began researching the phenomenon in the 1970s.

But half a century of behavioral research has failed to answer many fundamental questions about the brain mechanisms involved in the sense of effortless attention that exemplifies flow.

The Drexel experiment compared two conflicting flow theories to see which better reflected what was going on in people’s brains when they generated ideas. One theory suggests that flow is a state of intense hyperfocus on a task. The other theory posits that flow involves relaxing one’s focus or conscious control.

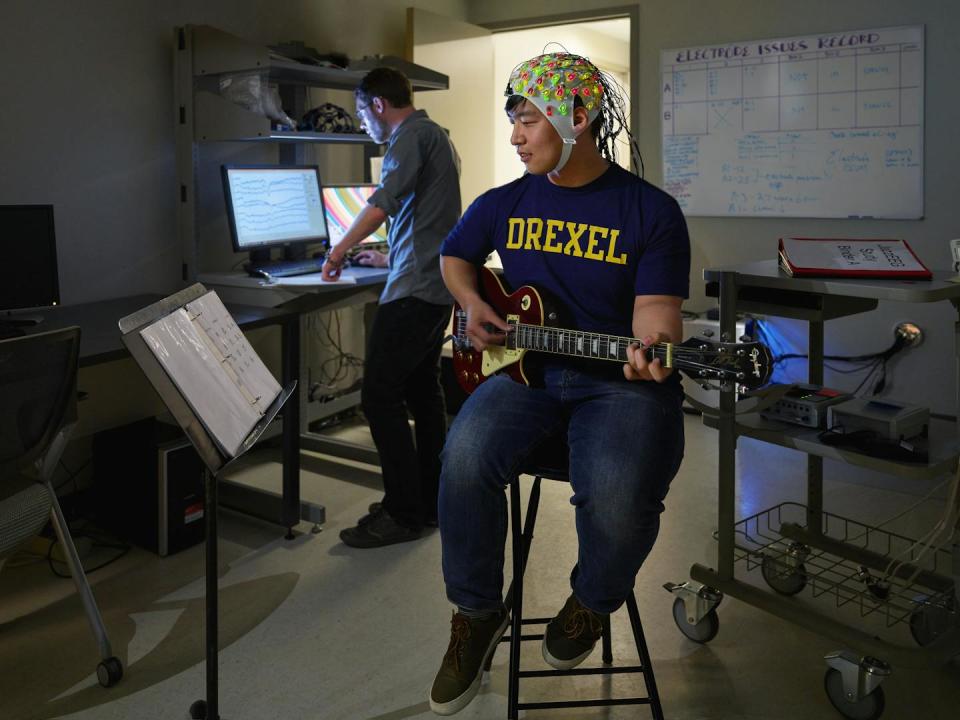

The team recruited 32 jazz guitarists from the Philadelphia area. Their experience levels, measured by the number of public performances they gave, ranged from novice to experienced. The researchers placed electrode caps on their heads to record EEG brainwaves as they improvised chord progressions and rhythms provided to them.

Jazz improvisation is a favorite tool for cognitive psychologists and neuroscientists who study creativity because it is a measurable real-world task that allows divergent thinking (generating multiple ideas over time).

Musicians self-rated the degree of flow they experienced during each performance, and these recordings were then heard by expert judges who rated them for creativity.

Train intensely, then surrender

Jazz master Charlie Parker is said to have advised: “You need to learn your instrument, then practice, practice, practice. And when you finally get on stage, forget all that and scream.”

This view is consistent with the findings of the Drexel study. Performances that musicians rated as high in flow were also rated as more creative by outside experts. Moreover, the most experienced musicians rated themselves as being more in flow than novices; this suggested that experience is a prerequisite for flow. Brain activities revealed why.

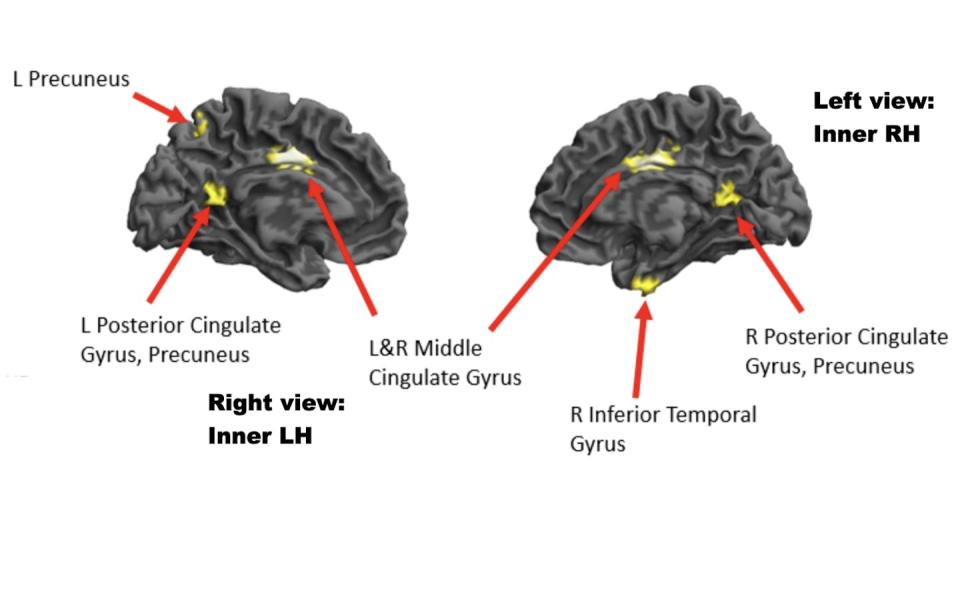

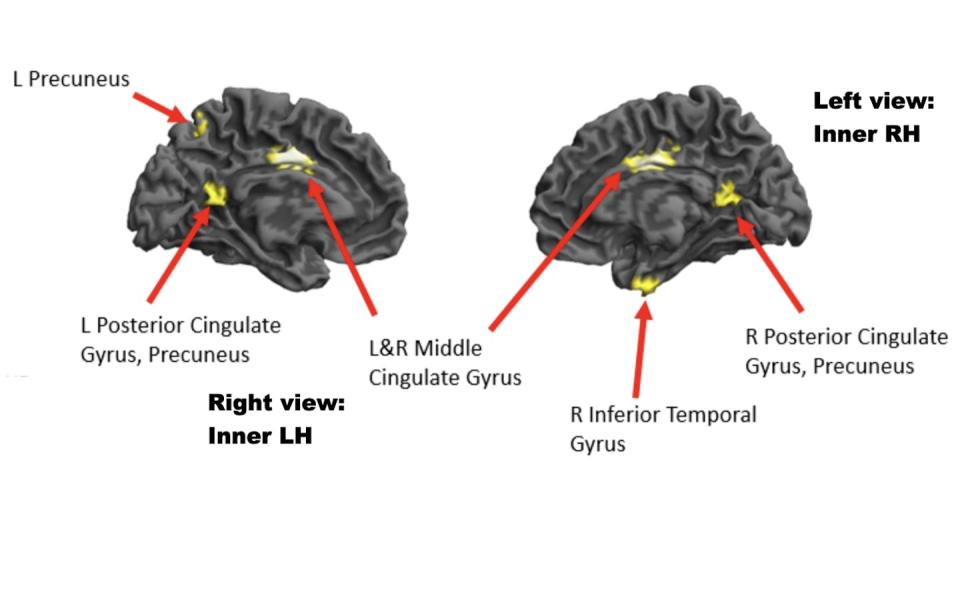

Musicians who experienced flow during performance showed decreased activity in parts of their frontal lobes known to be involved in executive function or cognitive control. In other words, flow was associated with conscious control, or loosening of control, over other parts of the brain.

And when the most experienced musicians performed in flow, they showed greater activity in areas of their brains known to be involved in hearing and vision; This makes sense, given that they improvise while reading chord progressions and listening to the rhythms provided to them. .

In contrast, the least experienced musicians showed little flow-related brain activity.

Flow and non-flow creativity

We were surprised to learn that flow state creativity is very different from non-flow creativity.

Previous neuroimaging studies have suggested that ideas are generally generated by the default mode network, a group of brain areas involved in introspection, daydreaming, and imagining the future. The default mode network spreads ideas like an unattended garden hose spraying water without direction. This goal is achieved by the executive-control network, located primarily in the frontal lobe of the brain, which acts like a gardener directing a hose to direct water to where it is needed.

The creative flow is different: no hose, no gardener. The default mode and executive control networks are suppressed so that they cannot interfere with the separate brain networks that highly experienced people create to generate ideas in their field of expertise.

For example, knowledgeable but relatively inexperienced computer programmers may have to reason through each line of code. But by tapping into brain networks specialized for computer programming, experienced coders can start coding fluently without much thought until they’ve completed the first draft of the program—perhaps in one sitting.

Coaching can be a help or a hindrance

Findings that mastery and the ability to surrender cognitive control are key to achieving flow are supported by a 2019 study from the Creativity Research Laboratory. For this study, jazz musicians were asked to play “more creatively.” Given this guidance, non-expert musicians were indeed able to improvise more creatively. Apparently this is because their improvisations are largely under conscious control and can therefore be adjusted to meet demand. For example, during the debriefing, one of the novice performers said: “I wouldn’t instinctively use these techniques, so I had to actively choose to play more creatively.”

On the other hand, expert musicians, whose creative processes were shaped by decades of experience, were unable to perform more creatively after being asked to do so. As one expert noted, “I felt stuck, and trying to think more creatively was a hindrance.”

The takeaway for musicians, writers, designers, inventors, and other creators who want to tap into flow is that training involves intense practice and then learning to step back and let one’s skill take over. Future research may develop possible methods for releasing control once sufficient expertise has been achieved.

This article is republished from The Conversation, an independent, nonprofit news organization providing facts and authoritative analysis to help you understand our complex world. Written by: John Kounios, Drexel University and Yvette Kounios, Widener University

Read more:

John Kounios currently receives grant funding from DiagnaMed Inc. for research on brain aging and has in the past received grant funding from the National Institutes of Health and the National Science Foundation for cognitive neuroscience research on memory, problem solving, and creativity.

Yvette Kounios does not work for, consult, own shares in, or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond her academic duties.