Astronomers have uncovered numerous hidden star clusters, including some violently exploding newborn protostars, as well as others that fall into an unexpected new category of ancient giant red stars. They call the second bodies “ex-smokers”.

The team says these ancient smokers lurk at the heart of the Milky Way, sitting quietly for decades before eventually fading away until they belch huge clouds of smoke. The stars were discovered as a result of a 10-year sky survey conducted with the Visible and Infrared Survey Telescope (VISTA) at the Cerro Paranal Observatory, high in the Chilean Andes. With this effort, tracking of almost 1 billion stars was achieved.

The same survey, known as VISTA Variables in Via Lactea (VVV), also revealed dozens of exploding protostars as the international team behind the study looked closely at 222 stars.

“About two-thirds of the stars were easy to classify as well-understood events of various types,” team leader and University of Hertfordshire professor Phillip Lucas said in a statement. “The rest were a little more difficult, so we used the Very Large Telescope (VLT) to obtain individual spectra of many of them. A spectrum tells us how much light we can see at different wavelengths and gives a much clearer idea of what we’re looking at.”

Relating to: An ‘extragalactic’ intruder may be lurking among the stars orbiting the Milky Way’s black hole

The stars detected by the team were hidden by the large amount of gas and dust that obscured our view of the heart of the Milky Way.

This material is very effective at absorbing visible light but is less adept at absorbing and blocking infrared wavelengths of electromagnetic radiation. This means that VISTA, with its cosmos-peering infrared eye, can actually peer through these clouds of gas and dust to reveal unseen stars near the center of the Milky Way.

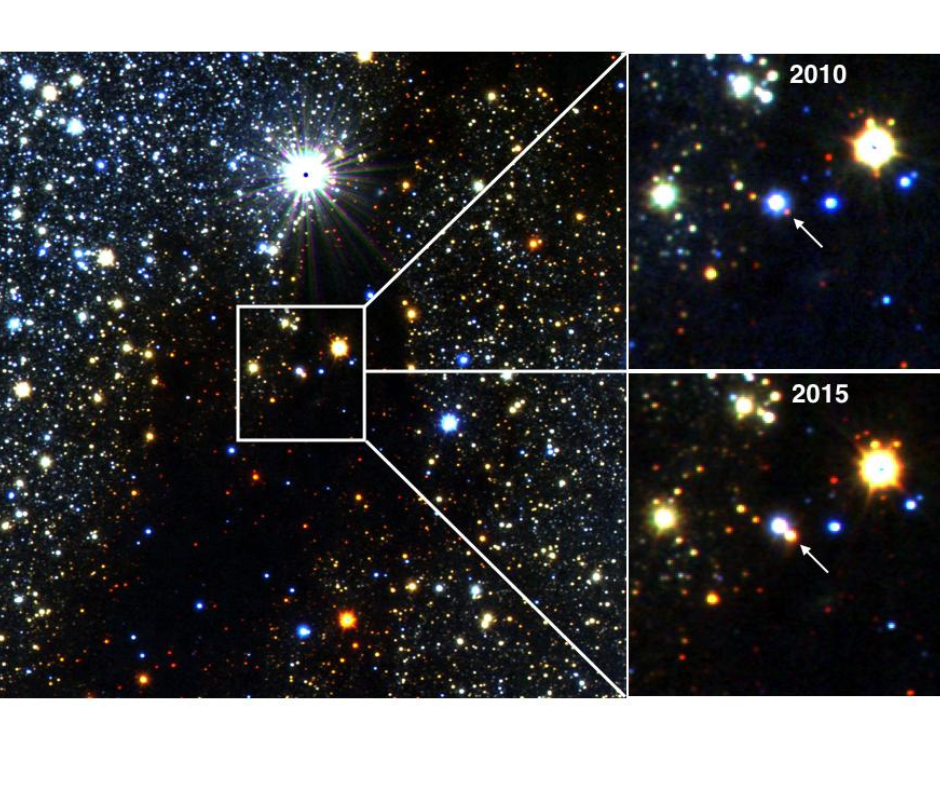

“Our main goal was to find rarely seen newborn stars, also called protostars, when they are experiencing a massive explosion that could last for months, years, or even decades,” said Zhen Guo, a team member and a scientist at Valparaiso University. , he said in the statement.

Protostars in young star systems undergo these extreme explosions when they accumulate enough mass from their natal gas envelopes to trigger the fusion of hydrogen into helium and become full-fledged stars, a process the team hopes to learn more about.

“These explosions occur in a slowly rotating disk of material that forms a new solar system. They help the newborn star in the middle grow, but make it difficult for planets to form,” Guo said. “We don’t yet understand why disks become unstable in this way.”

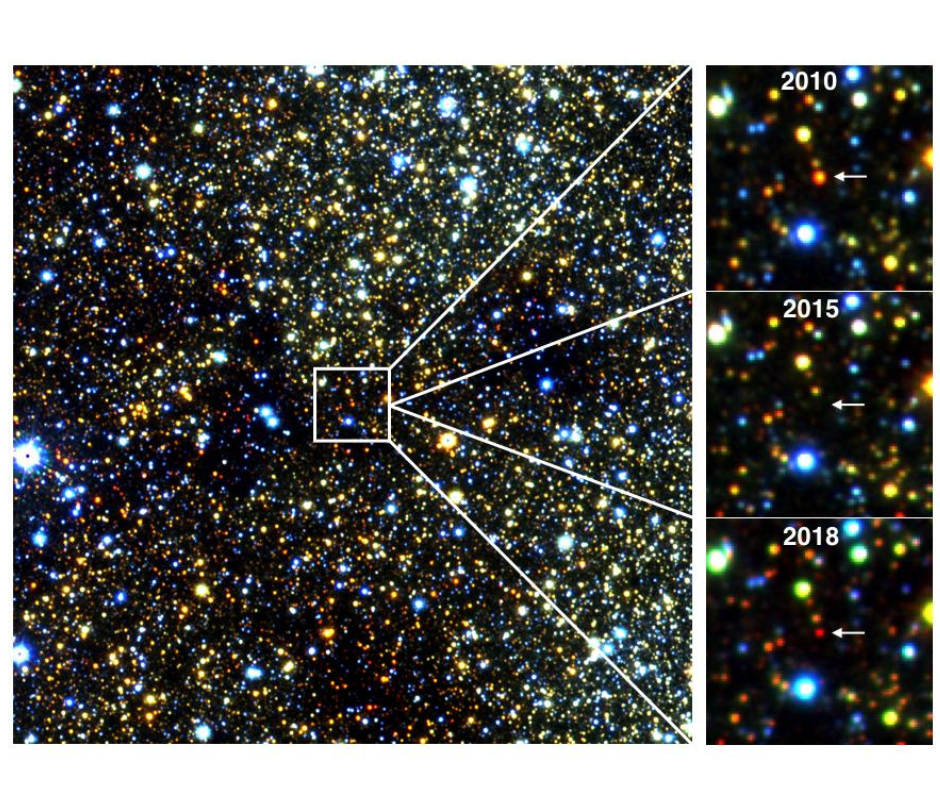

Astronomers say they have detected 32 “screaming” starlets experiencing brightness increases ranging from 40 to 300 times normal brightness.

In many of these protostars, the explosive events that trigger such increases in brightness are actually still occurring; This allows the team to study how these bursts evolve over time as their brightness increases, reaching peak brightness and then fading away.

While this is what astronomers were looking for with VISTA, their study of the heart of our galaxy also revealed something completely unexpected: a hitherto unknown type of star at the other end of the stellar life cycle.

Where do ‘old smoking’ stars hang out?

The VVV team discovered 21 red stars at the center of the Milky Way that showed difficult-to-explain changes in their brightness over several years.

“We weren’t sure whether these stars were protostars starting to explode, protostars recovering from a dip in brightness caused by a disk or dust shell in front of the star, or whether they were older giant stars shedding material in the late stages of their lives,” Lucas said.

Using the light spectra of 7 of these stars, the team eventually determined that they represented an entirely new type of giant red stars that sat quietly for decades and suddenly and unexpectedly released clouds of smoke, hence the name “old smokers.”

Former smokers are heavily concentrated in the innermost region of the Milky Way’s heart, known as the nuclear disk, where stars tend to have concentrations of elements much heavier than hydrogen and helium. Astronomers call these heavy elements “metals”.

Although the higher concentration of metals in these stars may help dust in outer layers of superheated gas or plasma condense more easily, it is currently unknown how this causes them to expel smoke.

The team thinks solving this puzzle could help better determine how the elements from which stars are made are distributed throughout the universe, as well as how they become the building blocks of new generations of stars and planets.

RELATED STORIES:

— Astronomers discover record distance of 25 new repeating ‘fast radio bursts’

— Hubble Space Telescope: Pictures, facts and history

— Record-breaking radio burst could help us find missing matter in the universe

“Matter ejected from old stars plays an important role in the life cycle of elements and helps form new generations of stars and planets,” Lucas said. “This was thought to occur primarily in a well-studied type of star called the Mira variable.

“However, the discovery of a new type of material-ejecting star may be of greater importance for the diffusion of heavy elements in the nuclear disk and metal-rich regions of other galaxies.”

The team’s research was published in two papers on Friday, January 26, in the journal Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society.