When I looked at the ceiling of the Paz theater in Belém’s old town, I thought I might see pink river dolphins. Maybe it was a touch of heatstroke. It wasn’t yet 9.30 and the weather was muggy. Soon the temperature will be 35°C and the temperature “feels like” above 40°C. Located at the mouth of the Amazon and just 1.5 degrees from the equator, the city was always sweltering, but summer had come early. I was seeing as much as possible before the real heat hit my home at lunch time.

Belém, capital of the state of Pará, flourished during the rubber boom of 1880-1912. There is grandeur everywhere, much of it worn and worn. But the theater is particularly well preserved. Artists had smuggled in local allusions. Wavy brown mosaics in the foyer symbolized the alluvial river; the frescoes showed a native girl who rejected European “science”; The angels had the colorful wings of forest birds.

I had lunch on the old docks, built with British iron in 1909. Next to it, Ver-o-Peso, the largest market in Latin America, is still a place where tropical fruits, meat and fish are traded. I visited the dazzling white cathedral and the basilica of Cirio, which were respectively renovated and built during the belle époque period. The rubber barons’ request to be buried in the second church (a request to get through the door despite their sinful lives, immense wealth, and slaves) is denied, but their surnames adorn the ceiling.

I loved Belém, with its Portuguese-tiled buildings, riverside hustle and bustle, and mangrove park full of scarlet ibises and iguanas. But I had come to pursue a human story; And not near the Atlantic, but deep in the jungle, down one of the branches of the Amazon. I came to visit the old rubber town of Fordlândia.

From where? Mainly curiosity. But the destruction of the Amazon is one of the great tragedies of our time. A past effort to colonize this place may provide insight. I recently returned to live in my native Lancashire and saw a lot of industrial ruins. They are sad, nostalgic, evocative, and important to people and history.

In 1928, Henry Ford decided to establish a rubber plantation in Brazil while he was rearranging production lines to produce the Model A, which he hoped would rival the new cars produced by the newly formed General Motors. Firestone took charge of rubber in Liberia. Dunlop and other British firms dominated Malaya. Ford went to the source: the Hevea brasiliensis tree. He would build a town next to the Rio Tapajós. He would send ships and his best men. He would pay local plumbers honest wages. Towards the end of 1929, thousands of saplings were planted. After that everything got a little complicated.

Exploring Belterra

From Belém, I flew an hour west to Santarém, another steamy riverside town with a wedding cake church, grocery store, ferry terminal, and seafood restaurants. Since 2003, it has been the local base for Cargill, the American company based in Minnesota that has turned millions of acres of the Amazon rainforest into dusty soy fields.

Before heading to Fordlândia, local guide and driver Paulo took me to visit a later development. Belterra was suggested by plant pathologist James Weir, mainly so that he could take credit for a new venture. I wasn’t expecting too much. I knew it wasn’t successful as a business venture. I knew that Amazon weather caused buildings to collapse and decay. However, thanks to preservation efforts and the quality of the original buildings, much of the old city remained in good condition.

The houses on Number One Street, also known as “salaried workers’ street,” had elegant roofs, shady porches, beautiful gardens, and clapperboards were still painted the same coded white and green as Ford built in company towns in Michigan. Upper Peninsula.

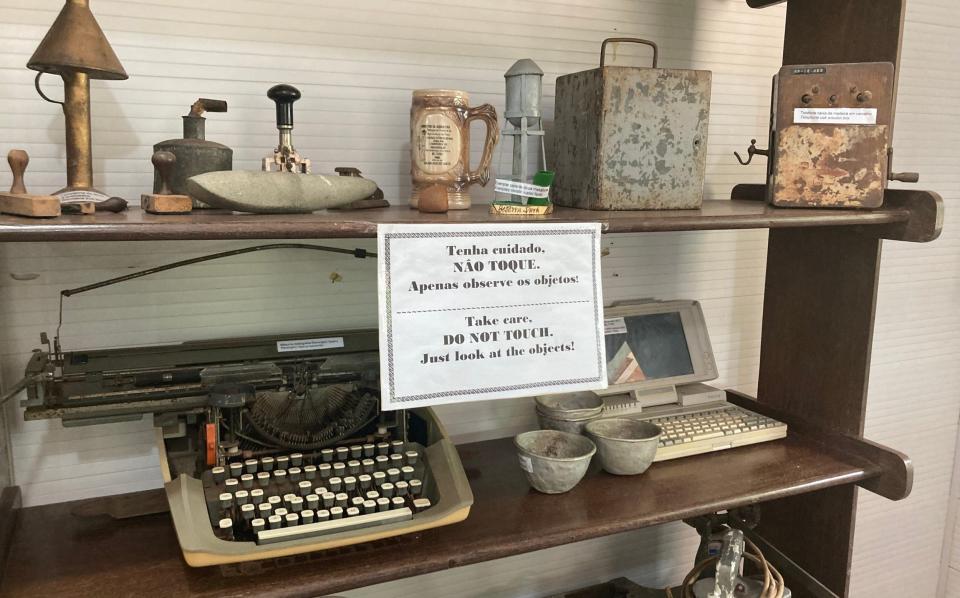

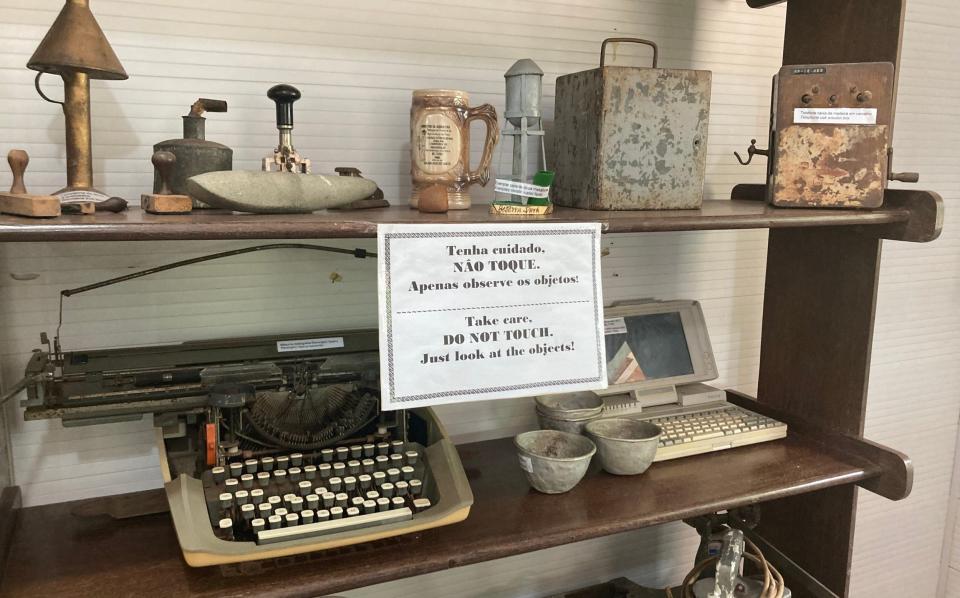

In Belterra’s small museum I met Antonio di Castro, who had just written the history of Fordlândia and Belterra. We chatted for more than an hour, and he showed me black-and-white photographs of plantation workers and old Ford cars repurposed as work vehicles. Exhibits included latex harvesters, a zinc bucket, old telephones, computers and oil lamps.

I mentioned that well-kept homes and Ford’s interest in gardening were good for the workers’ souls, especially to keep them away from bars and brothels. “Doña Clara gave awards to the best gardens in Belterra,” Antonio said, referring to Henry Ford’s wife. Holding out a handful of rubber seeds, he looked at me with a sly smile and said the name Henry Wickham. He was infamous in Brazil as a British explorer who smuggled rubber seeds from Brazil in 1876, launching the Asian rubber market and devastating the Amazon market.

On the way back, Paulo suggested taking a dip in a roadside stream. As I walked in, a local man pulled over and went down to the water for a drink.

“I hope you don’t have a caiman,” I joked.

His eyebrow wrinkled. “I doubt it. But probably sucuri.”

I looked at Paulo, who was translating the word “Anacondas.”

End of the road

I explored Eldorado in South America in search of beauty and riches. I have had false experiences of conquest, half-killing myself to reach an airy peak or a distant glacier. My trip to Fordlandia was, as the trope goes, Heart of Darkness. I could have gone by boat, but the tour operator had offered a six-hour trip; He had rented a Fiat Mobi, perfect for a snack at the supermarket. Almost no one goes to Fordlândia; so it was a shot taken in the dark.

Paulo arrived at 8.30am and we were soon on board the BR-163. One of Brazil’s megaroads connects the Amazon to the far south; a sign said Rio de Janeiro was 4,114 km away. It did not have a hardtop for holiday purposes, it was built for industry, it had two lanes and sometimes collided with trucks with double trailers and sometimes with convoys. It continued to be divided into asphalt, laterite and chaotic roadworks. I’ve seen near misses, sometimes I’ve seen nothing at all – driving blindly through a cloud of red dust – and I’ve seen two feet and a blanket: a death involving a soybean truck.

Finally, we turned right for the final stretch to Fordlândia – it was all dirt now. We checked into Pousada Americana, where a man named Guilherme fed us fried fish, rice, beans and fresh mangoes from his trees. After my nap, I met Magno, the local history teacher, who showed me around.

Uptown, the ruler’s houses were still standing, their roofs blown off, their paint stained and their plaster peeling off. One of them had been converted into a shuttered and decaying hotel (Hotel Zebu), with a swimming pool cracked by invasive vegetation.

The large old customs warehouse and warehouse on the river was a parking lot. One-ton rubber blocks were once stacked here for shipment to the United States. The old machine shop was still a business, but what remained of the original machines was rusty and dilapidated. Vulcanization equipment was dumped in the fields.

The most American-looking building, a rickety water tower, stood high above the town, but the famous handwritten letters that told passing boats they were near a Ford plant were long gone. The only example of the name I could find was on the bulging cylinder head of an ambulance that looked quite old but was definitely post-Ford.

A water pumping station on the river leaned steeply and looked as if it would soon sink. The fire hydrants placed on the streets were not connected to any pipelines. The old pier had lost half its length. The railway that ran deep into the rubber plantation was nowhere to be seen. However, a prison block still stood. Magno said people won’t be imprisoned for long as long as bad actors are let out. Most of the golf course has been taken over by the forest. Henry Ford approved of golf because golfers only looked forward.

It was a little depressing, but only a little. Because I knew beforehand that Fordlândia was a failure. I knew there were many reasons for this: the ignorance of its planners was greater than their idealism; Rubber trees growing healthily in the wild did not like to be planted as crops; Local workers rebelled against the harsh regime, terrible food, and disrespect shown by foreign rulers. Synthetic rubber was invented. After spending the equivalent of hundreds of millions of dollars, the site was abandoned in 1945; Henry Ford would sell the land to the Brazilian government for a few cents.

The locals seemed fond of their heritage. “People get emotional when they talk about Fordlândia,” Magno said. To think of a town in the Amazon in 1928 with running water, electricity, wages for workers, and homes to live in. Coming here was like winning the lottery. People competed to get one in five thousand jobs.” Guilherme was more measured: “Henry Ford was a visionary. But he never came here. There was a saying that everything at Amazon would grow. But he was deceived because he never hired an agriculturist who knew how to grow rubber. “He could work with cars, but not with plants.”

A visit to Fordlândia is much more than a nostalgia trip. Ford’s utopianism failed. Americans often expect others to live and work like them. The Brazilians refused. The expatriates grew pale from the heat, and no amount of quinine could keep away the snakes, jaguars, and dysentery. But where rubber refuses to grow, soybeans sprout. Agricultural industrialization, cattle farming, and deforestation are turning the Lower Amazon into flames, death, and destruction. In 1928, Fordlandia had a rainforest as its backdrop. Now charred trees lie everywhere like a great unknown.

how to

Humboldt Travel (01603 340680) organizes a 14-day Amazon holiday that visits Fordlândia and Belterra, as well as Belém, Alter do Chao, and culminates in a four-day journey from Manaus to the Rio Negro. Prices start from £5,970 per person including all accommodation, transfers, guides and all flights within Brazil.

How to get there

Tap Portugal flies direct from Lisbon to Belém for £795 return; Many airlines operate between UK airports and Lisbon; Latam flies to Santarém and Belém via São Paulo.