On a freezing afternoon, January 23, 1975, John Bonham sat in the back of a stretch Cadillac limousine, drinking vodka from a bottle. After Led Zeppelin had completed a three-night tour of the Chicago Stadium the previous night, the band’s next concert in St. Louis was cancelled because singer Robert Plant had fallen ill.

Lively discussions would soon begin aboard the band’s private jet, the “Starship,” about where its passengers might be taken for their impromptu 48-hour vacation. Bassist John Paul Jones fancied the Caribbean, while guitarist Jimmy Page hoped to head to Los Angeles. Their drummer, meanwhile, had no doubt about where he wanted to be.

“What the hell am I doing here?” Bonham asked as we headed to O’Hare Airport. “I want to go back House.”

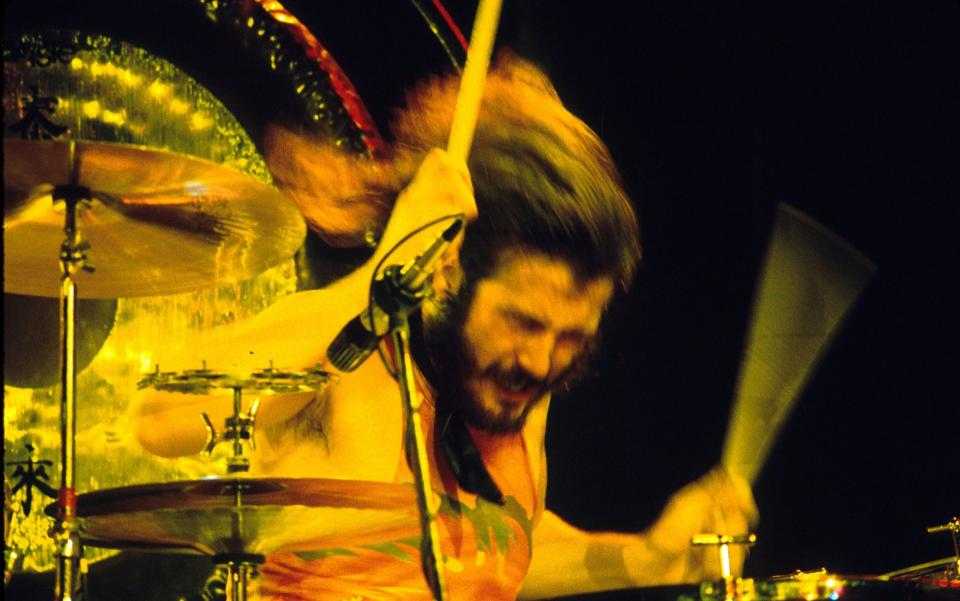

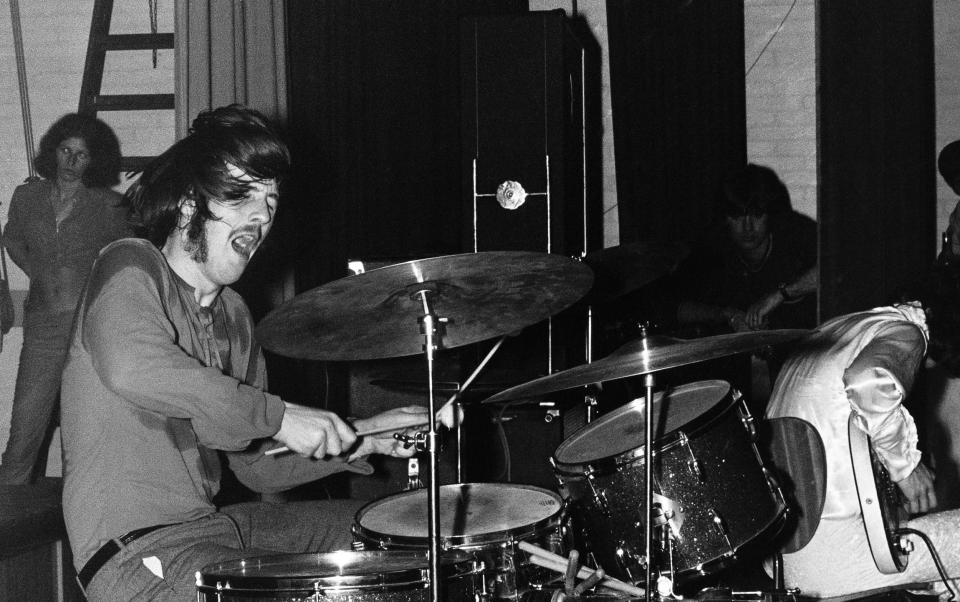

July 7th marks the anniversary of John Henry Bonham’s last live performance with Led Zeppelin. Less than three months after his final concert with the band’s original lineup at the Eissporthalle in West Berlin, one of the most revered and volatile drummers in rock history died after a day of heavy drinking at Jimmy Page’s Berkshire home on September 25, 1980. He was 32.

As Good Ship Zeppelin flew west toward Los Angeles in 1975, the traveling party was relieved to learn that “Bonzo” had retreated to a bed in the back of the plane to recover from his last drink. The mood was further softened after iron-fisted tour manager Richard Cole learned from journalist Chris Charlesworth, who was traveling in Bonham’s limousine, that the drummer had no intention of spiking his vodka with a handful of pills.

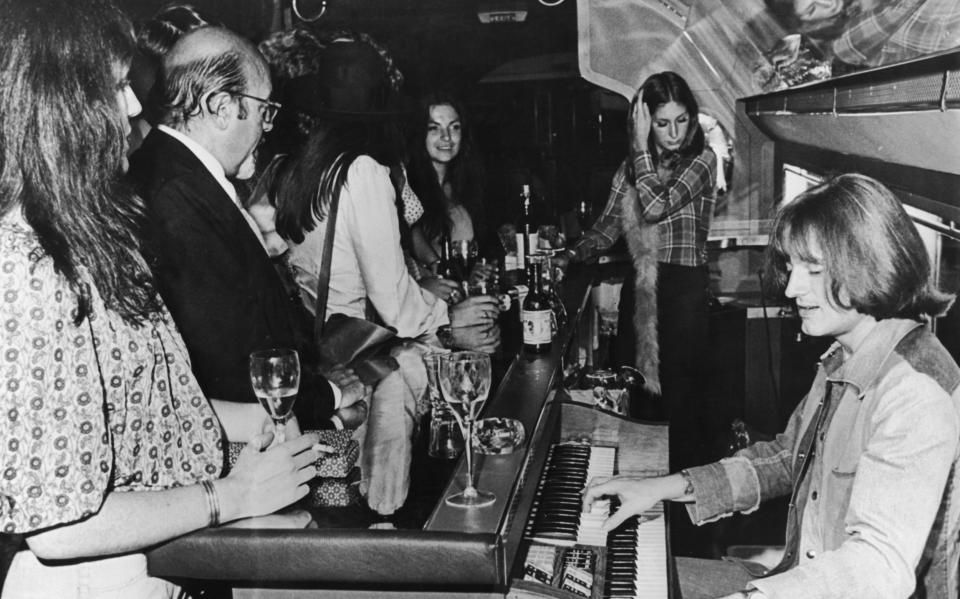

There was such an unusual air of joviality that after lunch and a few drinks John Paul Jones began playing a selection of music hall standards on an organ attached to the midships bar, and the band’s intimidating manager, Peter Grant, began shouting the lyrics to Any Old Iron at the top of his lungs.

And then…

“Bonzo, forgotten in the festivities, emerges from the bedroom in a baggy dressing gown, drunkenly staggers over to us and, before we’ve even been introduced, tries to do something very rude with one of the stewardesses,” Charlesworth recalls. “She’s probably three times his body weight. She screams. Grant and Cole drag Bonzo away from the distressed girl and force her back into the bedroom. She continues to scream. A pilot appears and demands to know what’s happened. I walk away. The pilot is furious. The girl is now sobbing, but Grant reappears and reassures her that everything is under control, while Page takes the hapless girl to a sofa where he calms her down with the usual clichés. Calm sets in.”

That this sordid tale remained untold for nearly 30 years may be explained by what happened next. “The rest of the journey was spent in silence,” Charlesworth said. “Cole went down [the press] He sat down. He’s not smiling. ‘I don’t want one single f______ word of that f______ word to find its way into your f______ magazines. Do I?”

To put it mildly, Led Zeppelin lived in a world of normalized dysfunction. By 1975, the band’s overseers and thugs had clearly understood that it was their sole duty to pamper and coddle the band’s four members. Peter Grant, both psychopathic and maternal, traveled with a large briefcase filled with thousands of dollars to get out of tight spots. A few days after John Bonham’s sexual assault, after a concert at the Greensboro Coliseum in North Carolina, the band’s manager threatened to steal a fleet of limousines that had been vandalized by ticketless fans after their driver (who had dropped his equipment) refused to sell them to him for $40,000 each. “You’ll regret it, you son of a bitch,” he warned.

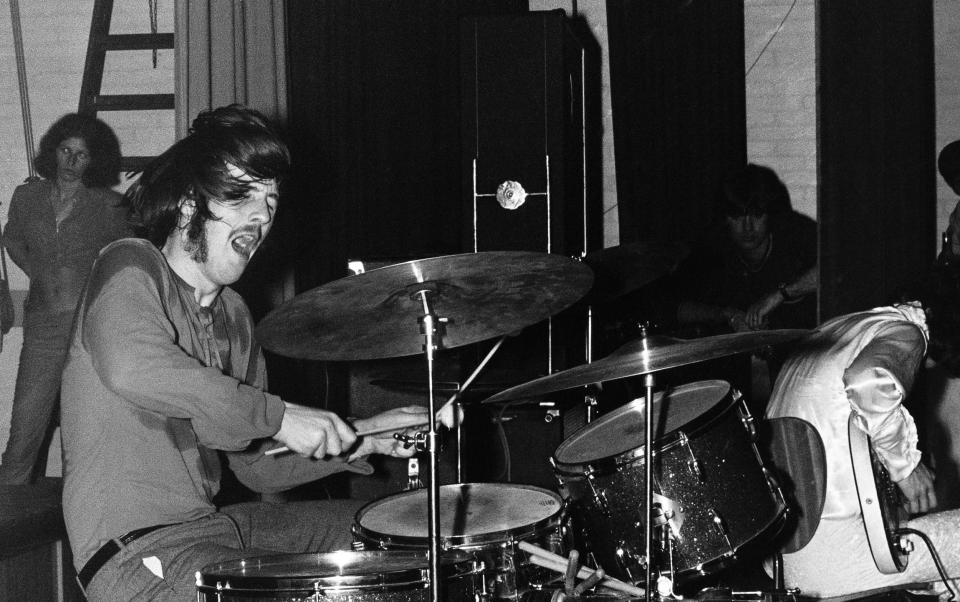

At least in America, Led Zeppelin led a carnival of madness from the start. On its first visit to Boston in January 1969, for example, the crowd at the Tea Party club was so loud that the band had to return to play the fresh-out-of-the-box self-titled debut album a second time, then return (for their own safety, it was said) for an hour of cover versions cobbled together in the dressing room. They were like rocket fuel to an audience that was captivated by their wild energy from sea to sea. Within seven months in Beantown, Led Zeppelin were headlining the 16,000-capacity Boston Garden.

In his extraordinary book Led Zeppelin: The Biography, author Bob Spitz astutely noted that at Tea Party the band were “still flirting, still getting to know each other, still developing a camaraderie.” They had been a unit for just over four months, brought together by Jimmy Page, “like a chef choosing ingredients for a recipe. Page and John Paul Jones had known each other as journeymen session musicians on the London studio circuit; Robert Plant and John Bonham were friends from the Midlands. There was a whiff of the North-South divide in the air, though no one would admit it.”

John Bonham was the home bird of the group. Many believed his road trip escapades were the result of boredom and missing his wife Pat and two children. In what was a harbinger of trouble to come, he had to be persuaded to join Led Zeppelin in the first place. He was already making good money in the clubs and bars of the West Midlands and was being offered a job drumming with Joe Cocker or rock and blues singer Chris Farlowe. The idea of joining a London start-up seemed like more trouble than it was worth.

But as a member of Led Zeppelin, he went down in history as a co-author of smash hits that managed to outsmart a media outlet accustomed to determining whether music producers could find an audience. Famously, when the band didn’t bother with singles, the press was (at best) skeptical. Commercially, it didn’t matter that their reviews were often dismissive and condescending.

The thing is, critics couldn’t figure out how the band’s young fans related to Led Zeppelin’s “electronic madness.” In fact, they couldn’t get enough of it. The convincingly immoral behavior that accompanied this wild electric excess may not have been a coincidence.

The hazy but consistent memories of the period tell of a culture of violence and intimidation, pianos thrown from eighth-floor hotel suites, alcoholism and drug addiction, and sexual encounters with young women who were children in the eyes of the law. Peter Grant traveled with a briefcase full of cash and a bag full of cocaine, which one onlooker described as a “scoop” as party favors.

In the middle of it all stood John Bonham, the band’s Dr Jeckyll and Mr Hyde. Lost as a lamb and ticking like a time bomb, the drummer was described by writer Pamela Des Barres as “a sweet, lovable, clumsy man until he got drunk and I wanted to avoid him. I saw him punch my friend Michelle in the jaw… because I was at the door with him at the Rainbow.” [in Los Angeles]Another coworker likened him to “a schizophrenic animal like in the movie Straw Dogs.”

Drugs were not much help either. “Taking cocaine allowed Bonham to drink more,” the music journalist Nick Kent wrote in Barney Hoskyns’s masterful oral history Trampled Under Foot. “The combination of cocaine and alcohol is almost as dangerous as heroin. It’s as if [members of the group’s entourage would say]”Whatever you do, don’t let him do drugs. He’ll take the whole gram and overdose.”

Despite everyone’s best efforts, the idea that actions could be separated from results was just a noisy illusion. In fact, life was keeping score. The band and their entourage were paying a hefty bill. In fact, the escalating cocaine paranoia had reached such a pitch that journalists aboard the Starship during its infamously ugly US tour in 1977 were presented with a document outlining the rules of engagement for anyone who found themselves in Led Zeppelin’s orbit.

It read: “1. Never talk to anyone in the band unless they’ve talked to you. 1A. Never make eye contact with John Bonham. It’s for your own safety. 2. Never talk to Peter Grant or Richard Cole – for any reason. 3. Always keep your cassette player off unless you’re doing an interview. 4. Never ask questions about anything except the music. 5. Most importantly, understand this – the band will read about them. The band don’t like the press, [and] “He doesn’t trust them either.”

Led Zeppelin’s career can be divided more or less neatly into two parts. Before the release of the double album Physical Graffiti in February 1975, the band’s extracurricular activities were a mere side dish to the music. But after that, inevitably, the chaos of it all began to take on a preponderance that could never be relinquished.

Writing in the New Yorker, critic James Wood correctly noted, “Things went downhill during the 1975 and 1977 tours. Page succumbed to drugs; Bonham was uncontrollable. The shows were dangerous, huge, flashy, and reckless. Page didn’t seem to notice or care that his guitar was out of tune. In 1975, Bonham played drums with a bag of cocaine between his legs; in 1977, he fell asleep on his drum kit. The crowds were riotous. The Detroit Free Press called the fans ‘the most violent, unruly crowd ever to enter a concert hall.'” (The phrase “concert hall” is a bit of an understatement here. In the Motor City, Led Zeppelin played the 75,000-seat Pontiac Silverdome.)

In other words, you can have great music and you can have dazzling stories—even both. But not for long. No matter how good you are, soon enough (and probably sooner than you think) you’ll have to decide which one you want to prioritize.

The beginning of the end was suitably ugly. Following a disagreement with John Bonham at the Day On The Green festival held at the Oakland Coliseum in the summer of 1977, Jim Matzorkis, a member of promoter Bill Graham’s security detail, was beaten bloodily by Peter Grant and another violent mob. Graham was outraged by the attack on both person and territory, and this would be the last time Led Zeppelin performed in the United States. Worse still, the band played only 18 more live shows in the three years before they disbanded following John Bonham’s death.

For less important actions, this might be fine. But in the 21st centuryst Century, with minimal effort, Led Zeppelin became more popular than they had been in the Seventies. In 2007, an announcement for a concert at the O2 Arena in memory of the late Atlantic Records executive Ahmet Ertegun led to 20 million people applying for just one of 20,000 tickets. Keeping the beat that night was John Bonham’s son Jason, whom fans of the band had first seen playing drums at the age of seven in the 1976 concert film The Song Remains The Same.

However, the juggernaut eventually came to a halt. From start to finish, Led Zeppelin had a Bonham in their ranks.