Using the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST), astronomers have found the most distant merger between supermassive black holes ever detected.

Colliding black holes are at the heart of merging galaxies so distant that the collision appears to have occurred just 740 million years after the Big Bang, when the 13.8 billion-year-old universe was a fraction of its current age.

Astronomers have long suspected that supermassive black holes with masses millions or even billions of times that of the Sun, found at the heart of most massive galaxies, are responsible for driving cosmic evolution. This new JWST finding shows that supermassive black holes have been in the driver’s seat almost since the beginning of time.

JWST regularly reveals supermassive black holes in the baby universe; This poses a problem since the unification process that facilitates their growth must take over a billion years. These results could also help solve the disturbing mystery of how supermassive black holes achieved enormous masses so early in the history of the universe.

Relating to: Falling into a black hole in mind-blowing NASA animation (video)

“Our findings suggest that mergers are an important pathway by which black holes can grow rapidly, even at the cosmic dawn,” study leader and Cambridge University scientist Hannah Übler said in a statement. said. “Together with other Webb findings of active, massive black holes in the distant universe, our results also show that massive black holes have shaped the evolution of galaxies from the very beginning.”

When quasars collide

Supermassive black holes devouring matter are at the heart of what astronomers call active galactic nuclei (AGN). These bright black holes power bright emissions from their central location, known as quasars, that can often dwarf the total light of every star in the rest of the galaxy around them.

These electromagnetic emissions have characteristic features that allow astronomers to determine that they originate from the feeding of supermassive black holes. These features can only be detected by telescopes in orbit around the Earth, and seeing them from the most distant quasars requires JWST’s extremely powerful and sensitive infrared eye.

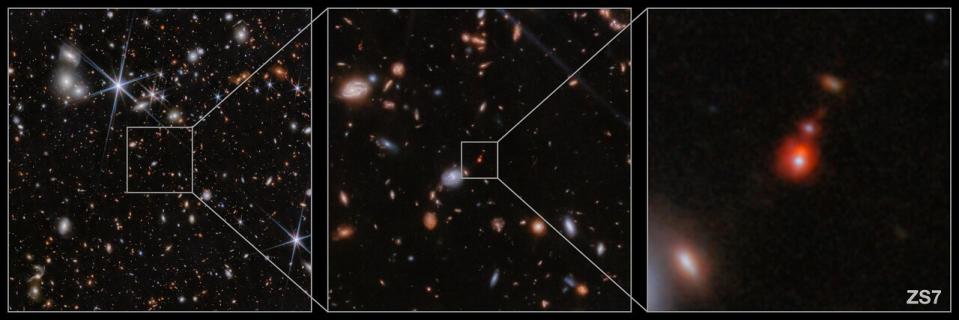

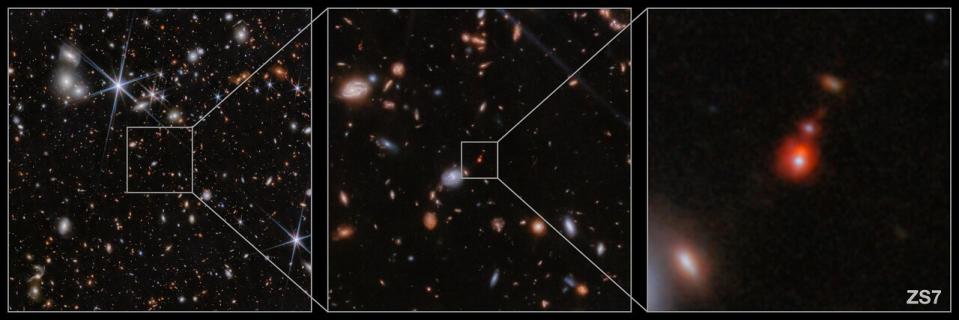

To search for quasars merging in the early universe, Übler and colleagues zoomed in on a galactic system about 12 billion light-years away called ZS7 with JWST’s Near Infrared Spectrograph (NIRSpec).

“We found evidence of very dense gas moving fast near the black hole, as well as hot, highly ionized gas that is often illuminated by energetic radiation produced by black holes during their accretion.” [feeding] “Thanks to the unprecedented sharpness of its imaging capabilities, JWST also allowed our team to spatially separate two black holes,” Übler explained.

The team determined that one of the supermassive black holes in this merger has a mass equivalent to about 50 million suns. They suspect that the second supermassive black hole has a similar mass, but scientists have not been able to confirm this with certainty due to the dense gas surrounding it.

“The stellar mass of the system we studied is similar to that of our neighbor, the Large Magellanic Cloud,” said team member Pablo G. Pérez-González, a scientist at the Centro de Astrobiología (CAB). “We can try to imagine how the evolution of merging galaxies might be affected if every galaxy had a supermassive black hole the size of or larger than the black hole in the Milky Way.”

When two supermassive black holes eventually merge, they would resonate the fabric of space with tiny ripples called gravitational waves. These will spread outward at the speed of light after the collision and will likely be detected by next-generation gravitational wave detectors.

This could include the first space-based system, the Laser Interferometer Space Antenna (LISA), an arrangement of three spacecraft developed by NASA and the European Space Agency (ESA) and planned for launch in 2035.

“The results of JWST tell us that lighter systems detectable by LISA should be much more frequent than previously assumed,” said Nora Luetzgendorf, ESA’s LISA Principal Project Scientist. said. “This will likely cause us to adjust our models for LISA rates in this mass range. This is just the tip of the iceberg.”

RELATED STORIES:

— How do some black holes get so big? The James Webb Space Telescope may have an answer

— Brightest quasar ever seen is powered by black hole eating ‘a sun a day’

—Black hole-like ‘gravastars’ could stack like Russian tea dolls

JWST will continue to search for early supermassive black holes even before LISA’s launch. Starting this summer, a program in the $10 billion telescope’s Cycle 3 operations will examine the relationship between massive black holes and their host galaxies in the first billion years after the Big Bang. This will involve searching for and characterizing mergers.

This could tell scientists at what rate supermassive black holes were colliding and whether this was enough to explain their rapid growth in the early cosmos.

The team’s research was published Thursday (May 16) in the journal The Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society.