Read in Spanish.

Southeast Michigan seemed like a perfect “climate paradise.”

“My family has owned my house since the ’60s. … Even when my father was a kid and lived there, there was no flood, flood, flood, flood. Until [2021]“A Southeast Michigan resident told us that June, a storm dumped more than 6 inches of rain on the area, overloading stormwater systems and flooding homes.

In our research on the past, present, and future of risk and resilience, we have found that the sense of living through unexpected and unprecedented disasters resonates with more Americans each year.

An analysis of federal disaster declarations related to weather events suggests more data behind the fears; the average number of disaster declarations has increased rapidly since 2000, nearly double the previous 20-year period.

As people question how livable the world will be in a warming future, a narrative around climate migration and “climate paradises” has emerged.

These “climate havens” are areas promoted by researchers, public officials and urban planners as natural refuges from extreme climate conditions. Some climate havens are already hosting people who are escaping the effects of climate change elsewhere. Many have affordable housing and legacy infrastructure from larger populations that began to leave before the mid-20th century, when industries disappeared.

But they are not disaster-proof or ready for a changing climate.

Six climate paradises

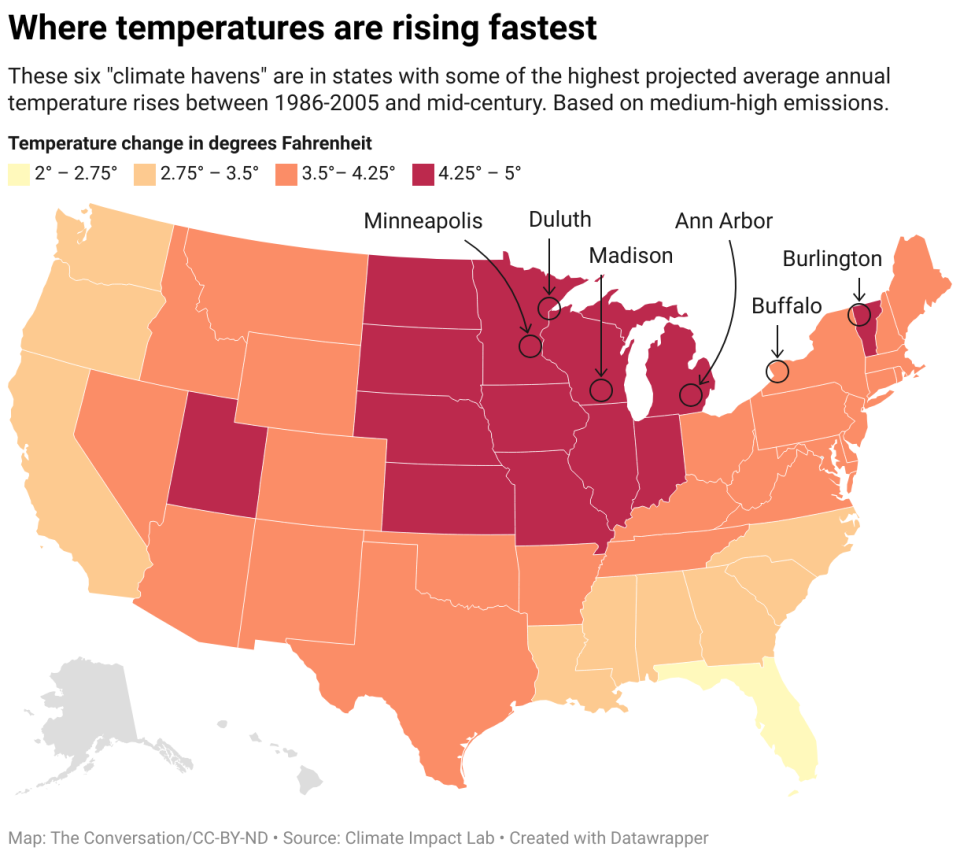

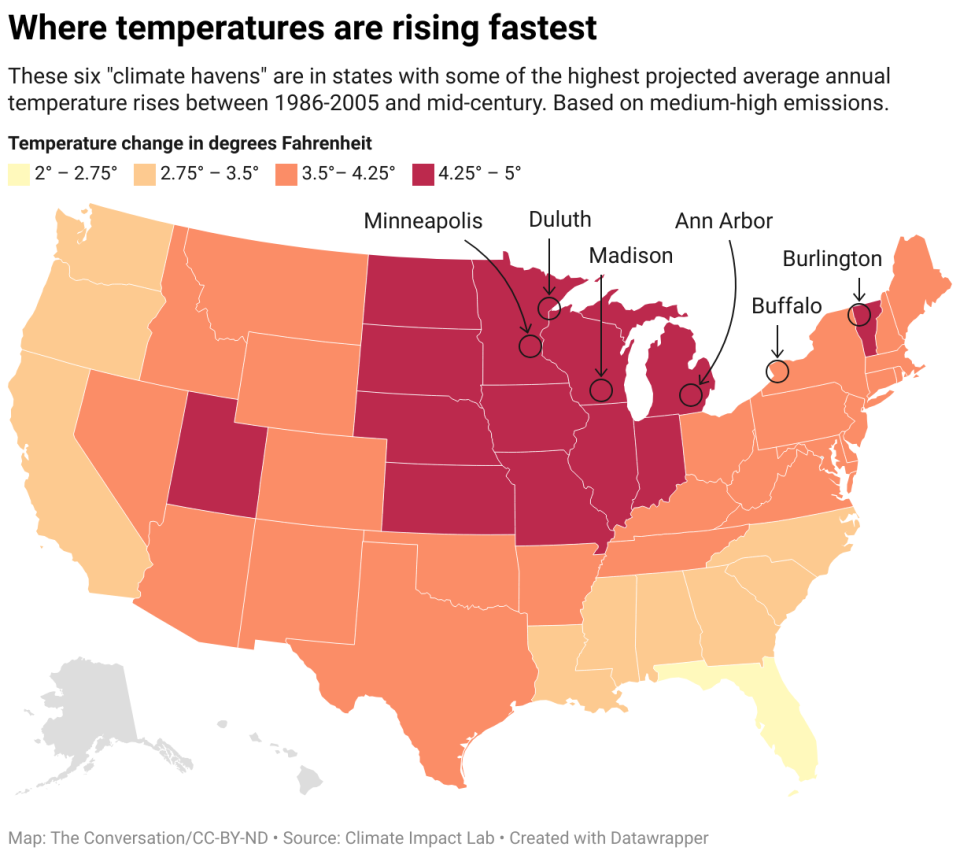

Some of the most frequently cited “refuges” in studies by national organizations and the news media are older cities in the Great Lakes region, the Upper Midwest, and the Northeast. These include Ann Arbor, Michigan; Duluth, Minnesota; Minneapolis; Buffalo, New York; Burlington, Vermont; and Madison, Wisconsin.

Yet each of these cities will have to cope with some of the country’s biggest temperature increases in the coming years. Warmer air also has a greater capacity to hold water vapor, resulting in more frequent, intense, and longer-lasting storms.

These cities are already feeling the effects of climate change. In 2023 alone, “refuge” areas in Wisconsin, Vermont, and Michigan were significantly damaged by powerful storms and floods.

The previous winter was also disastrous: Lake-effect snow, fed by moisture from Lake Erie’s still-open water, dumped more than 4 feet of snow on Buffalo, killing an estimated 50 people and leaving thousands of households without power or heat. Duluth experienced near-record snowfall and significant flooding in April as snowmelt caused by unseasonably high temperatures caused it to melt.

Heavy rainfall and extreme winter storms can cause widespread damage to the power grid and significant flooding, increasing the risk of waterborne disease outbreaks. These impacts are particularly pronounced in older Great Lakes cities with aging power and water infrastructure.

The old infrastructure wasn’t built for this

Older cities tend to have older infrastructure that was probably not built to withstand more extreme weather events, and they are now scrambling to strengthen their systems.

Many cities are investing in infrastructure improvements, but these improvements tend to be piecemeal, are not permanent solutions, and often lack long-term funding. They are typically not large enough to protect all cities from the impacts of climate change and may exacerbate existing vulnerabilities.

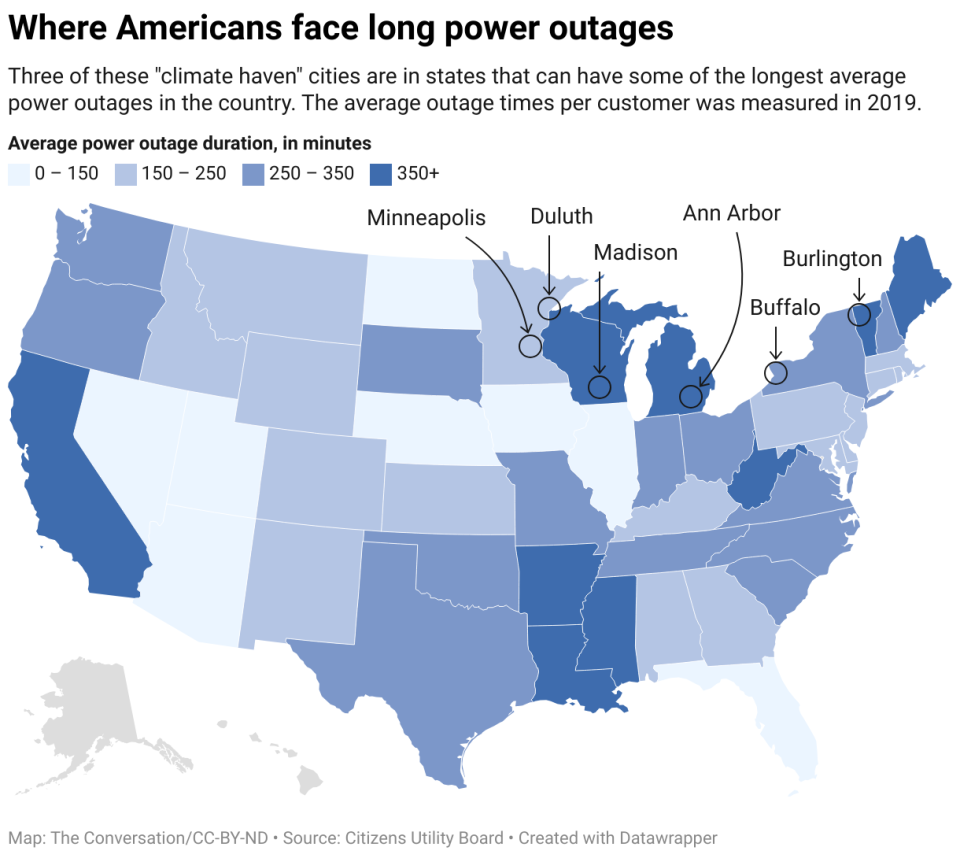

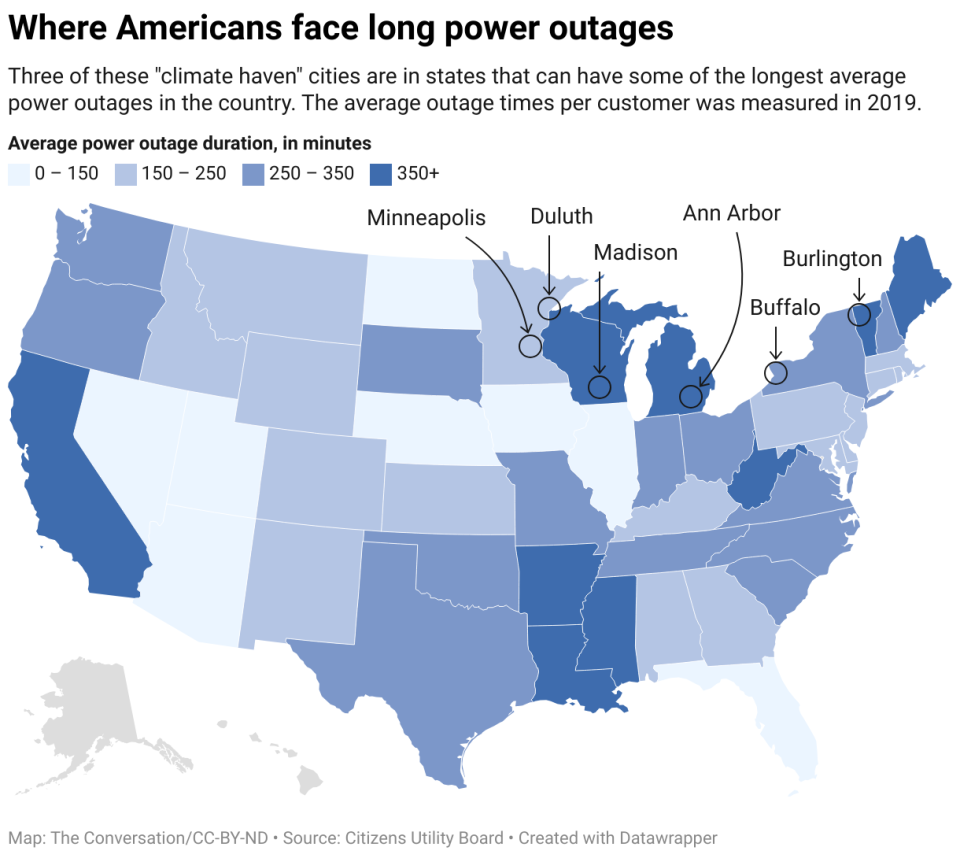

Electric grids are extremely vulnerable to the increased impacts of severe thunderstorms and winter storms on power lines. Vermont and Michigan rank 45th and 46th among states, respectively, in electric reliability, which includes the frequency of outages and the time it takes for power companies to restore power.

Stormwater systems in the Great Lakes region also routinely fail to cope with the heavy rainfall and rapid snowmelt caused by climate change. Stormwater systems are routinely designed based on National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration rainfall analyses called Atlas 14, which do not take climate change into account. A new version will not be available until 2026 at the earliest.

Compounding these infrastructure challenges is more frequent and extensive urban flooding in and around port cities. An analysis by the First Street Foundation, which incorporates future climate projections into its rainfall modeling, finds that five of these six port cities are at moderate or major risk of flooding.

Disaster notification data show that the counties in which these six cities are located have experienced an average of six severe storm and flood notifications since 2000, approximately every 3.9 years, and the number is increasing.

Heavy rainfall can further strain stormwater infrastructure, causing flooded basements, contaminated drinking water supplies in cities with outdated sewer systems, and dangerous road and highway flooding. Transportation systems are also struggling with higher temperatures and pavements that are not designed for extreme heat.

As these trends accelerate, cities everywhere will also have to address systemic inequalities in vulnerability, which often fall along lines of race, wealth, and mobility. Urban heat island effects, energy insecurity, and increased flood risk are just a few of the problems that climate change is intensifying and that tend to hit poorer residents harder.

What can cities do to prepare?

So, what should a safe city do in the face of climate change and population growth?

Decision makers can hope for the best, but they should prepare for the worst. That means working to reduce greenhouse gas emissions that drive climate change, but also assessing society’s physical infrastructure and social safety nets for vulnerabilities that become more likely in a warming climate.

It’s also important to collaborate across sectors. For example, a community may rely on the same water resources for energy, drinking water, and recreation. Climate change can affect all three. Working across sectors and including community input in climate change planning can help highlight concerns early.

There are many innovative ways cities finance infrastructure projects, including public-private partnerships and green banks that help support sustainability projects. For example, the DC Green Bank in Washington, D.C., works with private companies to mobilize funds for natural stormwater management projects and energy efficiency.

Cities will need to be vigilant about reducing emissions that contribute to climate change, while also preparing for climate risks that loom large even over the world’s “climate havens.”

This article is republished from The Conversation, a nonprofit, independent news organization that brings you facts and trusted analysis to help you understand our complex world. By Julie Arbit University of Michigan; Brad Altlar, University of Michiganand Earl Lewis, University of Michigan

Read more:

Earl Lewis is a member of the 2U Board of Directors; ETS Board of Trustees; American Funds/Capital Group Board of Directors; and the American Academy of Arts and Sciences Board of Trustees.

Brad Bottoms and Julie Arbit do not work for, consult, own shares in, or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and have disclosed no affiliations beyond their academic appointment.