One of the most common stereotypes about the human past is that men hunted and women gathered. This sexual division of labor, the story goes, provided the meat and plant foods people needed to survive.

The description of our time as a species dependent solely on wild foods until 10,000 years ago, when humans began domesticating plants and animals, matches the pattern observed by anthropologists among hunter-gatherers in the 19th and early 20th centuries. Almost all of the big game hunting they documented was carried out by men.

It is an open question whether these ethnographic accounts of labor truly represent the subsistence behavior of recent hunter-gatherers. In any case, they certainly fueled hypotheses that a sexual division of labor emerged early in the evolution of our species. Current employment statistics do little to disrupt this notion; According to a recent analysis, only 13% of hunters, fishermen and trappers in the United States were women.

Yet as an archaeologist, I have spent much of my career studying how people in the past obtained their food. I can’t always reconcile my observations with the “man the hunter” stereotype.

A long-standing anthropological assumption

First, I would like to point out that this article uses the phrase “women” to describe people who are biologically ready to experience pregnancy, but not everyone who identifies as a woman is so equipped, and not everyone who is so equipped identifies as a woman.

I use this definition here because reproduction is central to many hypotheses about when and why subsistence labor becomes a gendered activity. On reflection, women banded together because it was a low-risk way to provide a reliable flow of nutrients to dependent children. Men hunted either to supplement the household diet or to use the hard-to-obtain meat as a way to attract potential mates.

One of the things that bothered me about attempts to test relevant hypotheses using archaeological data (including some of my own) was that they assumed that plants and animals were mutually exclusive food categories. It all boils down to the idea that plants and animals are completely different in terms of their risk of acquisition, nutritional profiles, and abundance in the landscape.

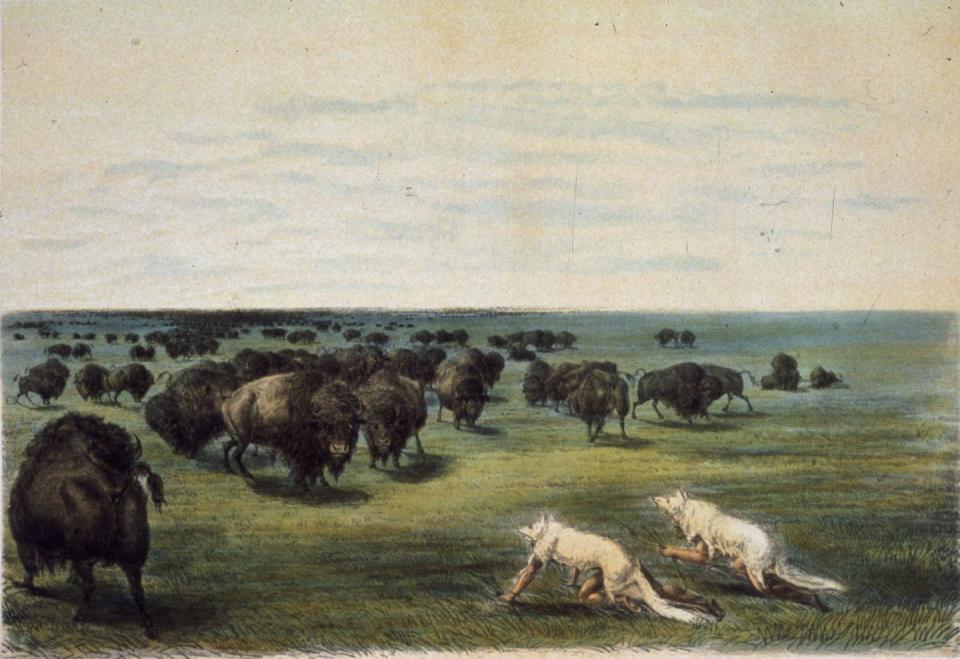

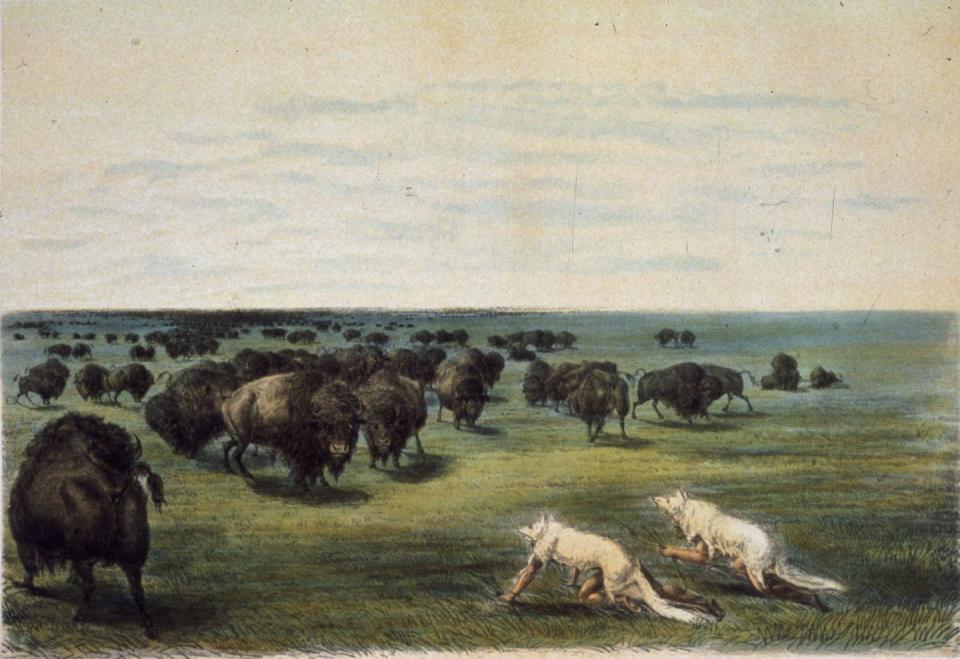

It is true that highly mobile large prey species such as bison, caribou, and guanaco (a deer-sized South American herbivore) sometimes concentrate in areas or during seasons when edible plants for humans are scarce. What if humans could get the plant part of their diet from animals themselves?

Animal hunting as a source of plant-based food

Plant material digested in the stomach and intestines of large ruminant herbivorous animals is a not very appetizing substance called digesta. This partially digested substance is edible by humans and is rich in carbohydrates that are almost completely absent in animal tissues.

Conversely, animal tissues are rich in protein and, in some seasons, fats; Nutrients that are not found in many plants or are present in such small amounts that a person would have to eat impractically large amounts to meet their daily nutritional needs from plants alone.

If humans in the past had eaten digestives, they would have been a large herbivore with a full belly, essentially a one-stop shop for complete nutrition.

To investigate the potential and consequences of digestion as a carbohydrate source, I recently compared institutional feeding guidelines to animal nutrition per person-day using a 1,000-pound (450-kilogram) bison as a model. I first compiled current estimates for the protein in a bison’s own tissues and the carbohydrates in its digestive tract. Using this data, I found that a group of 25 adults could meet the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s recommended daily protein and carbohydrate averages for three full days by eating only bison meat and one animal’s digestif.

Among people in the past, consuming digestive tracts may have eased the demand for fresh plant foods, perhaps changing the dynamics of subsistence labor.

Recalibrating risk if everyone gets hunted

One of the risks usually encountered in big hunting is failure. According to evolutionary hypotheses about the sexual division of labor, when the risk of hunting failure is high—that is, when the likelihood of bagging an animal on any given hunting trip is low—women should choose more reliable sources for procuring offspring, even if that means doing so. meetings lasting long hours. The cost of failure is too high to do otherwise.

However, there is evidence to suggest that big game was much more abundant in North America before, for example, 19th- and 20th-century ethnographers observed foraging behavior. Women might be more likely to participate in hunting if high-yield resources such as bison were available at low risk and the digestion of animals was also consumed. Under these conditions, hunting could provide a complete diet, eliminating the need to obtain protein and carbohydrates from separate sources, which would be widely dispersed.

Statistically speaking, women’s participation in hunting could also have helped reduce the risk of failure. My models show that if all 25 people in a hypothetical group participated in the hunt, rather than just the men, and if they all agreed to share when they were successful, each hunter would only need to be successful five times a year. The group will subsist entirely on bison and digestion. Of course, real life is more complex than the model suggests, but the exercise demonstrates the potential benefits of both digestion and female predation.

Ethnographically documented foragers regularly consumed digestive tracts, especially in places where herbivores were abundant but edible plants for humans were scarce, as in the Arctic, where the stomach contents of prey were an important source of carbohydrates.

I believe eating digesta may have been a more common practice in the past, but direct evidence is frustratingly difficult to obtain. In at least one example, plant species found in mineralized plaque on the teeth of a Neanderthal individual indicate digestion as a food source. To systematically study past digestive consumption and its knock-on effects, including female predation, researchers will need to draw on a wealth of archaeological evidence and insights from models such as the ones I have developed.

This article is republished from The Conversation, an independent, nonprofit news organization providing facts and authoritative analysis to help you understand our complex world. Written by Raven Garvey university of michigan

Read more:

Raven Garvey does not work for, consult, own shares in, or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond his academic duties.