Sign up for CNN’s Wonder Theory science newsletter. Explore the universe with news about fascinating discoveries, scientific breakthroughs and more.

A new analysis of the tracks has revealed that three-toed fossil footprints dating back more than 210 million years had their feet pressed into soft mud by bird-like bipedal reptiles.

Footprints found in various parts of Southern Africa were recently determined to be the oldest bird-like tracks ever found; These footprints predated the oldest known skeletal fossils of birds by about 60 million years.

Dr., a lecturer in geological sciences at the University of Cape Town in South Africa. “Given their age, it is likely that these were made by dinosaurs,” Miengah Abrahams said. Abrahams is the lead author of the new study describing the tracks, published Tuesday in the journal PLOS One.

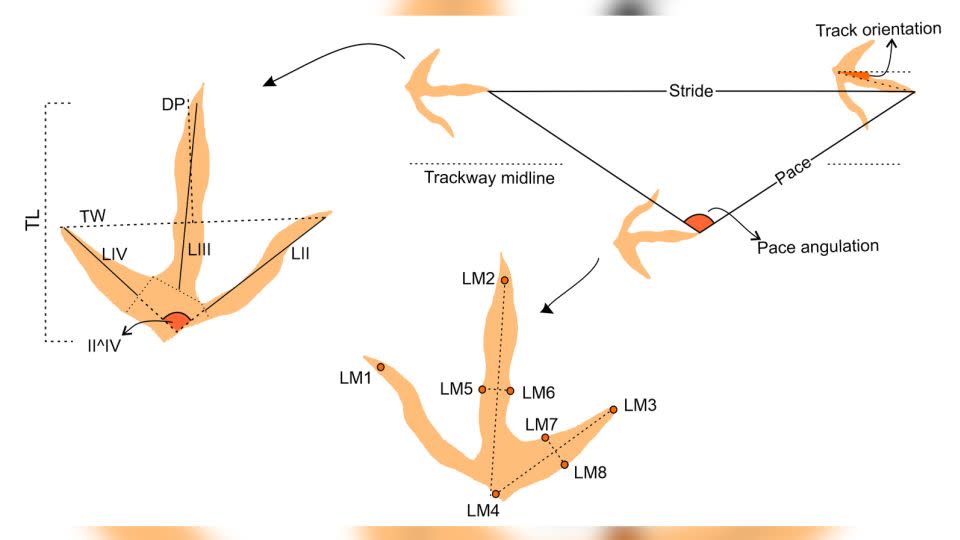

Theropods, including Tyrannosaurus rex, were a diverse group of bipedal meat eaters with three-toed feet. However, among these newly examined dinosaur tracks, there were also ones that were different from typical theropod tracks. The outliers have a shorter extension of the central digit, a much wider spread and “significantly narrower toes,” which look more like bird footprints, Abrahams told CNN in an email.

However, since the animals that created the tracks are unknown, their relationship with birds is unclear. The tracks may represent a missing clue about the evolution of birds, or they may belong to reptiles with bird-like feet that were not close to the bird lineage but evolved independently, the researchers reported.

boneless fossils

The footprints were discovered in the mid-20th century and given the scientific name Trisauropodiscus by French paleontologist Paul Ellenberger. The name is an ichnogenus, meaning that it describes a genus based on trace fossils, or the fossilized impressions left behind, rather than fossils of an animal’s body.

Seven ichnospecies are thought to be linked to Trisauropodiscus tracks, and paleontologists have debated for decades over the group’s affinity to birds. Some said the tracks were bird-like, but others weren’t so sure. Abrahams said Ellenberger may have muddied the waters by assigning many different shaped tracks to ichnogenus “and not all of them were bird-like.”

Moreover, the shape of the footprint can vary greatly depending on the type of material the animal steps on. This can make it difficult to pinpoint the physical characteristics of extinct animals when the only clues they leave behind are fossilized traces, Dr. Julia Clarke, a professor of vertebrate paleontology at the University of Texas at Austin, was not involved in the research.

“The footprints are a truly unique record,” Clarke told CNN. “But there will always be a zone of uncertainty inherent in the data we have.”

At the time that traces of Trisauropodiscus were stamped in the mud, evolutionary adaptations were exploding in archosaurs (an ancient reptile group that includes dinosaurs, pterosaurs and crocodiles), so finding evidence of bird-like feet in an unknown member of this group was intriguing, he added. .

“The footprints do not directly correspond to any known animal fossils from this region and period. “These may belong to other reptiles or cousins of dinosaurs that evolved bird-like feet,” said Clarke. “This adds to our understanding of morphological diversity in the archosauria during this really important time period.”

following in footsteps

The researchers’ investigation began in 2016: Abrahams said the UCT team “followed in the footsteps of Paul Ellenberger and documented his sites using modern technological standards.”

During a trip to Maphutseng, a fossil site in Lesotho, the team found a series of bird-like tracks from the Triassic Period. “It took us a minute to realize we were looking at Trisauropodiscus,” he said. “Our first impression was that these tracks did indeed look like birds, and we knew we needed to investigate them further.” This required visits to fossil sites; analysis of archival photographs, sketches and patterns; and creating 3D digital models of footprints.

Scientists examined 163 pieces and divided them into two categories, or morphotypes, based on their shape. Fragments categorized as morphotype I were labeled as nonavian. These fingerprints were slightly longer than wide; they had rounder, sturdier, and narrowly spread toes. “They also have a distinctive ‘heel,’ which consists of the pads of the third and fourth toes,” Abrahams said.

Morphotype II tracks were smaller in comparison. They were wider than they were tall and had thinner toes. This second group of tracks was very similar in shape and wide spread of its fingers to tracks from a bird from the Cretaceous Period (145 million to 66 million years ago): the wading bird Gruipeda, another ichnogenus known only from footprints. Scientists reported that, in general, Morphotype II tracks are very similar to modern bird tracks.

The oldest fossil evidence for paravians, the dinosaur group that includes the oldest birds and their closest relatives, occurs in the mid-Jurassic Period (201.3 million to 145 million years ago); Morphotype II Trisauropodiscus traces, dating back at least 210 million years, indicate that bird feet are much older.

“Trisauropodiscus shows that bird-like foot morphology is much older, a feature shared between modern birds and other Late Mesozoic archosaurs,” Abrahams said. said. “This research contributes to our collective ongoing understanding of the evolution of dinosaurs and birds.”

Mindy Weisberger is a science writer and media producer whose work has appeared in Live Science, Scientific American, and How It Works magazines.

For more CNN news and newsletters, create an account at CNN.com