Sign up for CNN’s Wonder Theory science newsletter. Explore the universe with news about fascinating discoveries, scientific advances and more.

Excavations and metal detector work at the site of a famous ship burial in Suffolk, England, have revealed missing pieces that could help archaeologists better understand the intriguing but unfinished sixth-century artifact.

A team of archaeologists, volunteers and conservationists have uncovered additional fragments of a Byzantine-era beehive at Sutton Hoo, where the discovery of the ship burial in the late 1930s transformed historians’ understanding of Anglo-Saxon life.

Made of a thin copper alloy, the bucket depicts a North African hunting scene, with warriors armed with various weapons, as well as lions and a hunting dog. The Greek inscription at the top reads, “To Mr. Count in good health, many happy years.” The letters helped researchers date the vessel to the sixth century.

Experts meticulously cleaned, reshaped and reassembled parts of the Bromeswell bucket, which was found in 1986 and 2012. The pieces are on display in the site’s High Hall exhibition to show visitors how the bucket once looked.

New research at Sutton Hoo has not only uncovered more fragments of the bucket, but also provided new insights into the history of the ship, which once travelled from Antioch in modern-day Turkey, part of the Byzantine Empire, to the east coast of Britain.

“It’s like a jigsaw puzzle that’s been added to over the years,” said Laura Howarth, archaeology and engagement manager at the National Trust’s Sutton Hoo site.

Putting together an old puzzle

A tractor rake first uncovered fragments of the artefact in 1986, when the Tranmer family owned the Sutton Hoo site before it became part of the National Trust.

Metal detector searches in 2012 revealed more parts of the hive.

Researchers are trying to determine whether modern farming practices had disrupted and dispersed the pieces of the bucket, or whether it was intentionally left in pieces. Other burials contained fragments of other buckets that appeared to have been deliberately cut into smaller pieces before being placed in the ground, Howarth said.

The research team also wants to know the purpose of the bucket: Was it buried as a luxury item in a grave, or did it store food, drink or cremated remains?

“It was a kind of luxury import that came to (now) modern England, but when I think about some of the Anglo-Saxons who held it or used it and who had perhaps never seen a lion or could not read Greek, I see them thinking, ‘Wow, what is this?'” Howarth said.

Analysis is ongoing for new fragments found in newly dug pits at Garden Field in June. Careful excavations have revealed what appears to be a hand belonging to one of the figures in the bucket. The team decided to remove the fragments and the surrounding soil “in blocks.”

Researchers removed the large block from around the bucket fragments, carefully wrapped them and placed them in a tray to analyze the soil around the fragments, Howarth said.

Soil analysis can help determine when the hive was buried and how it was used.

Two other Byzantine buckets have been found in England, including the Breamore bucket from the Rockbourne Roman Villa archaeological site and museum in Hampshire. The Breamore bucket, also featuring an ancient Greek inscription and armed warriors, was probably made in a sixth-century workshop in Antioch.

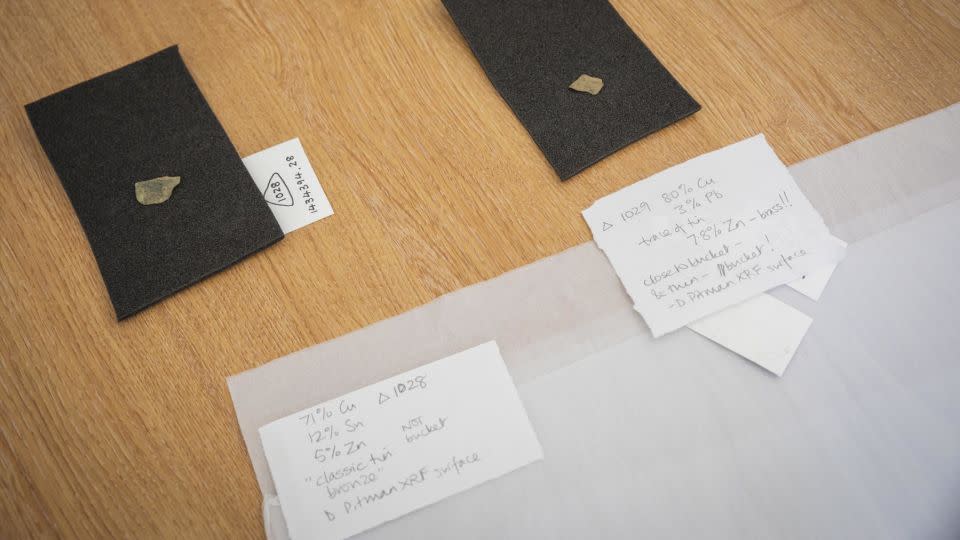

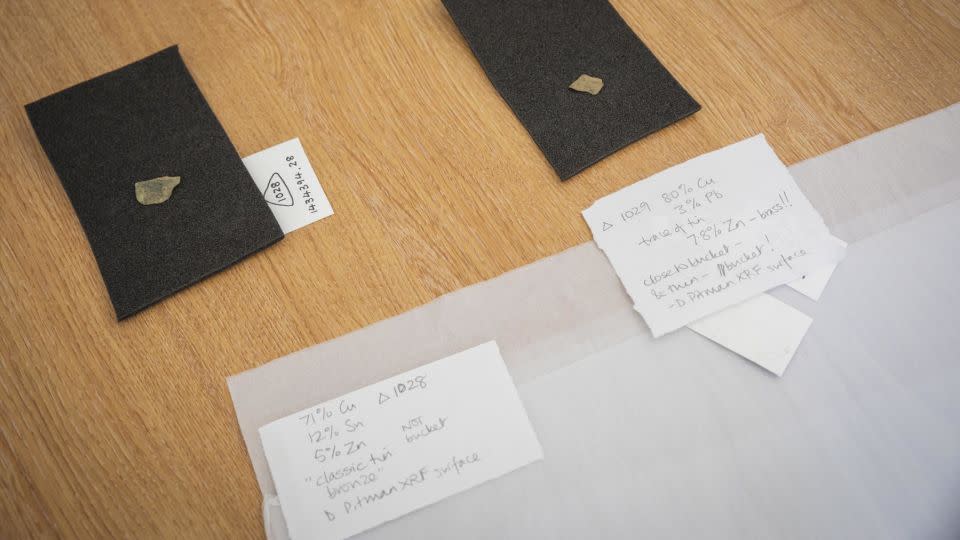

The team used an X-ray fluorescence instrument, similar to a ray gun, to perform a chemical and elemental analysis on the newly found fragments, confirming that they were part of the Bromeswell bucket.

The team also confirmed that some unidentified metal fragments collected during a metal detecting operation in 2012 belonged to the bucket.

Based on the shapes of the Greek letters on the top of the artifact, researchers thought the ship was already 100 years old when it arrived at Sutton Hoo, Howarth said. The new analysis adds to that theory.

“On closer inspection, we think the hive had been previously damaged and then repaired,” the National Trust’s regional archaeologist Angus Wainwright said in a statement. “Further analysis of the metals suggests it may have even been re-soldered.”

An archaeological treasure

The new research at Sutton Hoo is part of a two-year project led by the National Trust, Field Archaeology Specialists (FAS), Heritage and the “Time Team”, which has been turned into a British television online show.

The aim of the project is to gain greater insight into the prehistoric and early medieval history of Sutton Hoo. With more than 80 volunteers, the team searched the Garden Field with metal detectors and 3D recorded the recovered objects. Some of the volunteers included members of the 1980s excavations at Sutton Hoo and an organisation that enables people with mental health issues to use archaeology and heritage as part of their wellbeing.

“A lot of people who were strangers came together but left as friends,” Howarth said.

More discoveries from the June excavations and metal detecting efforts will be shared in a “Time Team” documentary early next year, and once the finds have been processed and catalogued, they will be returned to Sutton Hoo. Eventually, the pieces of the hive will be reassembled into the exhibits. At present, some of the sides and base of the hive are missing.

The project also completes an ongoing documentary by Time Team about the reconstruction of the Anglo-Saxon ship that made Sutton Hoo famous.

‘Ghost’ ship

The ship grave, one of three known Anglo-Saxon ship burials, was discovered between 1938 and 1939, as World War II approached.

The Pretty family moved to the Sutton Hoo estate in 1926 and Edith Pretty arranged for the excavation of the burial mounds, which were located 457 metres from her home.

The 90ft (27.4m) long wooden ship was dragged half a mile (0.8km) down the River Deben when an Anglo-Saxon warrior king died 1,400 years ago. The burial was probably that of Raedwald of East Anglia, who died around 624, and was placed inside the ship, surrounded by treasures and buried in a barrow.

The ship’s planks rotted in the acidic soil, but the precise positioning of the planks left a mark in the sand, as well as rows of iron rivets.

The excavations unearthed Byzantine silverware, jewelry made of precious metals and gems, garnets from what is now Sri Lanka, an iron warrior’s helmet, and a banqueting set. Pretty donated the treasures to the British Museum, where a curator declared it “one of the most important archaeological discoveries of all time.”

Since then, excavations have continued at Sutton Hoo, uncovering both royal and public burials dating to the sixth and seventh centuries. There is also evidence of earlier settlers, such as Roman conquerors.

Future research at Sutton Hoo could reveal the broader history of the site and what enabled people to continue settling there over time, Howarth said.

“I also think it’s really nice that it maintains some of its mystery,” Howarth said.

“Sometimes at these famous archaeological sites I think people expect everyone to have all the answers. But there are still so many questions and answers that we don’t know. The aim of this project is to look at the landscape and think about who lived there and how that fits into the wider Sutton Hoo story.”

For more CNN news and bulletins, create an account at CNN.com