The fault that ruptured beneath New Jersey on Friday morning was an ancient, dormant seam in the Earth that was likely awakened by geological forces in a region where earthquakes are rare and seismic risks are poorly understood.

The 4.8 magnitude earthquake was the strongest earthquake in New Jersey in more than 200 years.

The United States Geological Survey said at a press conference that more earthquakes were possible; statistical modelers predict a 3% chance of a magnitude 5 or greater earthquake in the coming weeks.

A magnitude 4.0 aftershock occurred in New Jersey on Friday evening. The USGS website reports at least 11 aftershocks in the area so far. The USGS said statistical models based on past earthquakes suggest there could be 27 aftershocks of magnitude 2 or greater next week.

As the shaking calmed down Friday, scientists began working to determine exactly where the rupture occurred.

“This is an area with many old faults that could reactivate at any time. The fault that caused the earthquake is currently unknown,” said USGS research geologist Jessica Jobe.

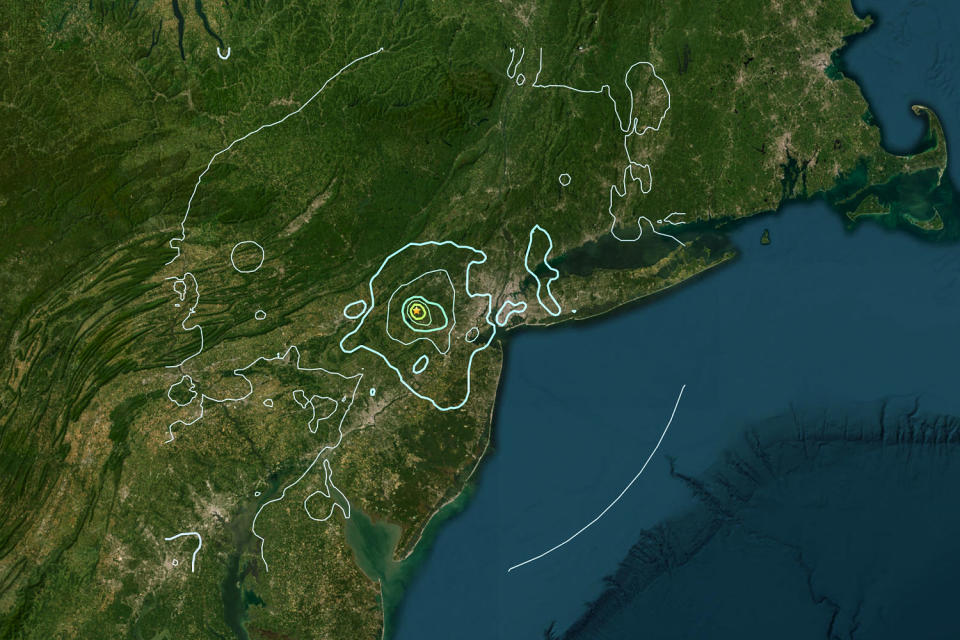

Scientists suspect that the earthquake likely originated in the Ramapo fault zone area in the Newark basin. The fault system includes a branching fault network. Some have been mapped but others are probably unknown; Therefore, it is possible that the fault where the Friday earthquake occurred has been mapped.

“It probably occurred due to an unnamed fault, but we don’t really know. “It’s hard to figure that out where there’s so much complexity,” said USGS geophysicist Dara Goldberg. “It could be on a branch of the Ramapo fault. It could be something adjacent, we’re not quite sure.”

Scientists said the fault area is old and complex. Determining exactly what happened will help researchers understand what to expect from the region in the future and better address seismic risk in the Northeast.

Unlike the West Coast, where tectonic plates meet at a boundary and create a seismic hazard along the coast, the Northeast’s tectonic risk has its roots in ancient history: Faults arise from tectonic processes that are no longer in operation. scattering of cracks and weaknesses.

Stress slowly accumulates on this fault network and sometimes causes slippage, causing earthquakes, said Frederik J. Simons, a professor of earth sciences at Princeton University.

“Stress continues to increase at very slow rates,” Simons said. “Like the creaking and groaning of an old house.”

Compared to the West Coast, earthquakes on the East Coast can be felt from greater distances and can cause more significant tremors depending on their size because the rocks in the region are generally older, harder and denser.

“These are talented rocks that conduct energy well,” Simons said.

Friday’s earthquake was felt widely from Washington D.C. to Boston. It was also pretty shallow; The USGS said it likely ruptured less than 3 miles below the Earth’s surface.

“The shallower it is or the closer it is, the more we feel it as humans,” Simons said.

However, the intensity of earthquakes in the region is limited by the length of the faults.

“The magnitude of the earthquake is directly proportional to the length of the moving fault,” Goldberg said. “The faults are not very long in the Northeast.”

Felix Waldhauser, a seismologist and research professor at the Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory, said the quake underscores the need to better understand the region’s earthquake risk.

“We don’t understand the mistakes here very well. If we don’t understand the errors, it’s hard to assess the danger,” Waldhauser said.

He lamented that the USGS cut funding for the Lamont-Doherty Cooperative Seismography Network in 2019; He said there once were 45 stations collecting seismic data in the Northeast but are now down to about 20.

“In an ideal world, we would have our network working, recording the data, and analyzing the data to find exactly where the incident occurred,” he said.

Waldhauser said Friday afternoon that he was trying to rally his colleagues to place seismometers around the epicenter of the quake near Whitehouse Station in New Jersey to record aftershocks that could help identify the main fault line.

“We’re trying to bring people together. I’m not sure if it’s going to happen,” he said.

But a dense network of local equipment is most useful for monitoring smaller earthquakes and conducting detailed science, but is not a requirement for understanding larger quakes like Friday’s, Goldberg said.

“Anything of magnitude 4 we can detect at a global array of stations,” he said. “Given the magnitude of earthquakes that affect society and people’s daily lives, we can do well without this intensity.”

Simons, who grabbed his jacket and rushed out of his Princeton office at the moment of the quake, said the 35-second “violent, powerful and long” tremor made for an exciting morning and a reminder to the country’s less seismically active coasts. “It’s like getting a warning – a mini stroke, a heart attack,” he said.

“The world gives us energy that we cannot control. Let’s continue to build good buildings, enforce building codes, and do disaster preparedness so we can respond when the next disaster strikes,” Simons said.

This article first appeared on NBCNews.com.