Were dinosaurs already on the brink of extinction when an asteroid hit Earth 66 million years ago, ending the Cretaceous, the geological period that began about 145 million years ago? This is a question that has been bothering paleontologists like us for more than 40 years.

In the late 1970s, debate arose as to whether dinosaurs were at their peak or in decline before their great extinction. At the time, scientists noted that dinosaur diversity increased in the geological phase spanning 83.6 million to 71.2 million years ago, while the number of species in the scene decreased in the last few million years of the Cretaceous. Some researchers have interpreted this pattern to mean that the asteroid hitting the Gulf of Mexico was the final blow to an already vulnerable group of animals.

But others have argued that what appears to be a decline in dinosaurs’ diversity may be a result of how difficult it is to count them accurately. Fossil formations can more or less preserve different dinosaurs, depending on factors such as their preferred environment and how easily their bodies fossilized there. The accessibility of various outcrops may influence the types of fossils researchers have found so far. These biases are a problem because paleontologists must rely on fossils to answer definitively how healthy dinosaur populations were when the asteroid hit.

What was actually happening to dinosaur diversity at that critical moment? The discovery, identification and identification of new dinosaurs provide vital clues. This is where our study comes into play. Close examination of what we thought was a juvenile specimen of an already known dinosaur species from this period revealed that it was actually an adult fragment of an entirely new species.

Focusing on the life stage of our specimen, our study shows that dinosaur diversity did not decline before the asteroid impact, but rather that there are more species from this period yet to be discovered; potentially even through the reclassification of fossils already in museum collections. .

Clues in the bones of a bird-like dinosaur

Our new study focused on four hindlimb bones: a femur, a tibia, and two metatarsals. These were unearthed in rocks from the Hell Creek Formation in South Dakota and date back to the last 2 million years of the Cretaceous.

When we first examined the bones, we determined that they belonged to a family of dinosaurs known as caenagnathids, which are bird-like dinosaurs with toothless beaks, long legs, and short tails. Direct fossil and excavated evidence shows that these dinosaurs were covered in complex feathers, just like modern birds.

The only known caenagnathid species from this time and region Anzu, sometimes called the “chicken from hell.” Covered in feathers, sporting wings and a toothless beak, Anzu It weighed roughly 450 to 750 pounds (200 to 340 kilograms). Despite its scary nickname, its diet is a matter of debate. It was probably an omnivore, eating both plant material and small animals.

Because our sample was significantly smaller. Anzu, we assumed it was a child. We attributed the anatomical differences we noticed to its juvenile state and smaller size, and reasoned that the animal would have changed if it had continued to grow. Anzu Specimens are rare and no definitive offspring have been published in the scientific literature; so we were excited to look inside his bones and potentially learn more about how he grew and changed throughout his life.

Just like the rings of a tree, bone records rings called growth arrest lines. Each annual line represents a part of the year when the animal’s growth slows down. They would tell us how old this animal was and how fast or slow it was growing.

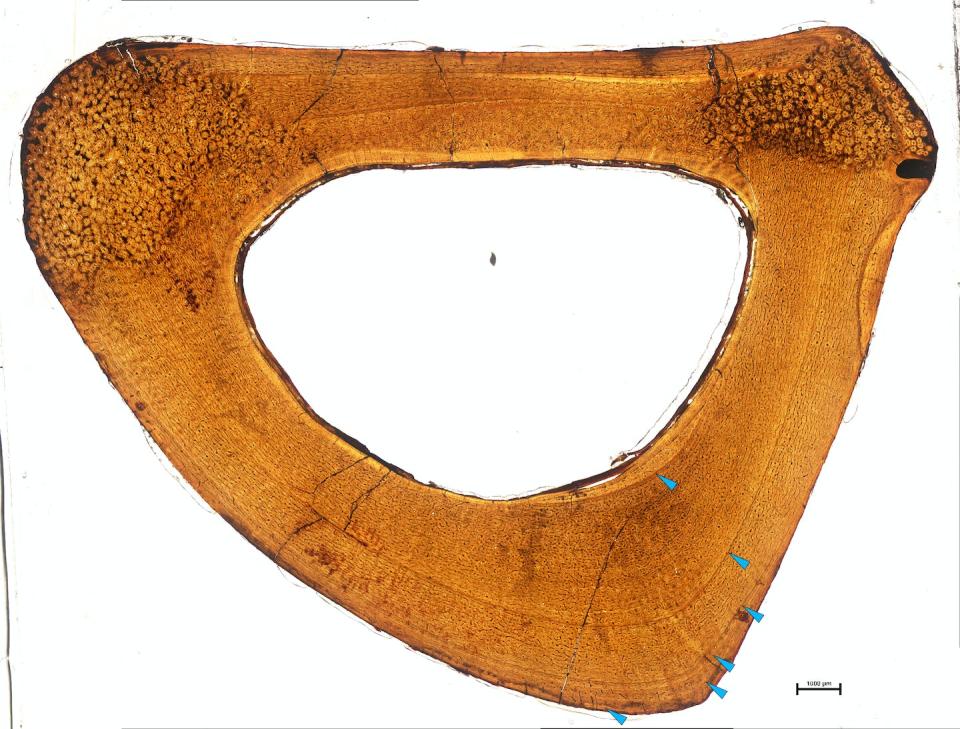

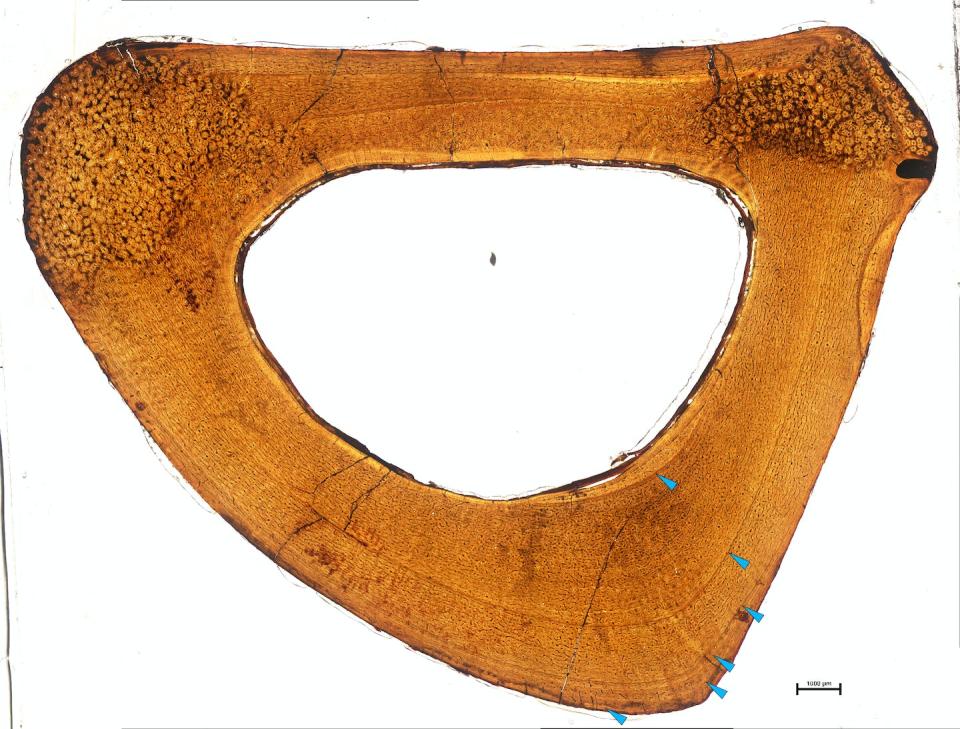

We cut the middle of three bones to be able to microscopically examine the internal anatomy of the sections. What we saw completely shattered our initial assumptions.

In a young person, we would expect the arrested growth lines in the bone to be widely spaced, indicating rapid growth, and to have equal spacing between the lines from the inside of the bone to its outer surface. Here we saw that the later lines were getting closer and closer together; This suggests that this animal’s growth slowed and it reached almost adult size.

This was not young. Instead, it was an adult of an entirely new species. Eoneophron infernalis. His name means “Pharaoh’s Chicken in Hell” and is a reference to his older cousin’s nickname. Anzu. Features unique to this species include ankle bones fused to the tibia and a well-developed protrusion on one of the foot bones. These were not the characteristics of a teenager Anzu will grow, but the unique aspects of the smaller Eoneophron.

Expanding the caenagnathid family tree

With this new evidence, we began to make extensive comparisons with other members of the family. Eoneophron infernalis fits into the group.

This also inspired us to re-examine other bones previously believed to have existed. AnzuWe now knew that more caenagnathid dinosaurs lived in western North America at that time. A specimen with a smaller partial foot bone than our new specimen looked different from both. Anzu And Eoneophron. Once upon a time there was one “Hell chicken”, now there were two, and there was evidence of a third: one big (Anzu), about the weight of a brown bear, a medium size (Eoneophron), similar in weight to a human, and one small but yet unnamed, close in size to a German shepherd.

When we compare Hell Creek to older fossil formations such as the famous Alberta Dinosaur Park Formation, which preserves dinosaurs that lived between 76.5 and 74.4 million years ago, we find not only the same number of caenagnathid species but also the same size classes. There, we have it. caenagnathuscomparable Anzu, chirostenotescomparable EoneophronAnd citipsIt is comparable to the third type for which we found evidence. These parallels in both number of species and relative sizes provide compelling evidence that caenagnathids remained stable throughout the latter part of the Cretaceous.

Our new discovery shows that this group of dinosaurs did not decrease in diversity at the very end of the Cretaceous. These fossils show that there are still new species to be discovered and support the idea that at least part of the pattern of declining diversity is the result of sampling and preservation biases.

Did the big dinosaurs go extinct in the humorous way a Hemingway character quipped about going bankrupt “gradually, then suddenly”? While there are still many unresolved questions in this extinction debate, Eoneophron It adds evidence that the caenagnathids were in pretty good shape before the asteroid destroyed everything.

This article is republished from The Conversation, an independent, nonprofit news organization providing facts and analysis to help you understand our complex world.

Written by: Kyle Atkins-Weltman, Oklahoma State University and Eric Snively, Oklahoma State University.

Read more:

The authors do not work for, consult, own shares in, or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and have disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic duties.