Tropical forest landscapes are home to millions of Indigenous people and small-scale farmers. Even though the claims are not officially recognized by governments, they are spoken for on almost every square meter of land.

As the world tries to slow climate change and restore deforested tropical landscapes for a healthier future, these local landowners hold the key to a valuable solution.

Tropical forests are vital to Earth’s climate and biodiversity, but today a football field-sized area of mature tropical forest is burned or cut down approximately every 5 seconds to make room for crops and cattle.

Even though these trees are lost, the land still has potential. Tropical forests’ combination of year-round sunlight and high rainfall can lead to high growth rates; This suggests that areas where tropical forests once grew may be valuable areas for reforestation. In fact, many international agreements and declarations foresee exactly this.

But for reforestation projects to have an impact on climate change, they need to work with and for the people living there.

As forest ecologists interested in tropical forest restoration, we explore effective ways to compensate for ecosystem services from people’s lands. In a new study, we show how compensation that also allows landowners to harvest and sell some trees can provide powerful incentives, ultimately benefiting everyone.

The extraordinary value of ecosystem services

Tropical forests are celebrated for their extraordinary biodiversity, and their protection is seen as essential to preserving life on Earth. These are reservoirs of vast carbon stocks that slow climate change. But when tropical forests are cleared and burned, they release copious amounts of carbon dioxide, a greenhouse gas that causes climate change.

Programs that offer payment for ecosystem services are designed to help keep forests and other ecosystems healthy by compensating landowners for nature-produced goods and services that are often taken for granted. For example, forests regulate stream flows and reduce flood risks, support bees and other pollinators that benefit neighboring cropland, and help regulate climate.

In recent years, a cottage industry has developed that pays people to reforest land for the carbon it can sequester. This has been driven in part by companies and other institutions seeking to meet their commitments to reduce greenhouse gas emissions by paying for projects to reduce or avoid emissions elsewhere.

Early iterations of projects that pay landowners for ecosystem services were criticized for focusing too much on economic efficiency, sometimes at the expense of social and environmental concerns.

Win-win solutions that take both environmental and social concerns into account may not be the most economically efficient solution in the short term, but they can lead to long-term sustainability as participants feel a sense of pride and responsibility for the success of the project.

This long-term sustainability is essential for trees to store carbon, as decades of growth are required to create the stored carbon and combat climate change.

Why timber can be a triple win

In the study, we looked for ways to maximize three priorities in forest restoration (environmental, economic and social benefits) by focusing on unproductive lands.

This may seem surprising, but most soils in the tropics are extraordinarily infertile; Concentrations of phosphorus and other essential nutrients are much lower or lower than in crop-producing regions of the northern hemisphere. This makes restoring tropical forests through reforestation more complex than simply planting trees; These areas also require maintenance.

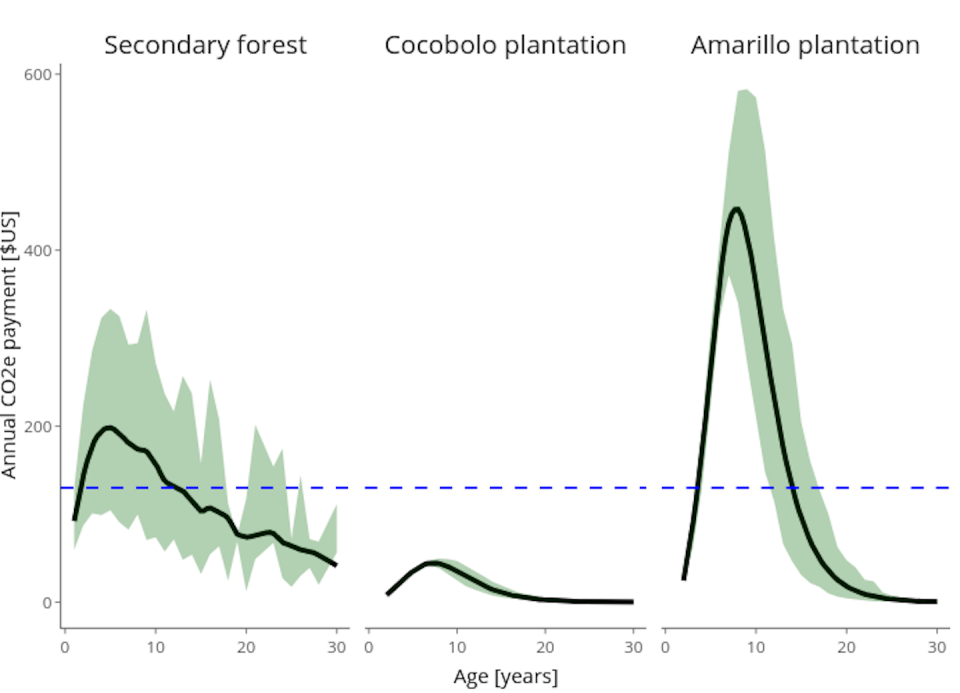

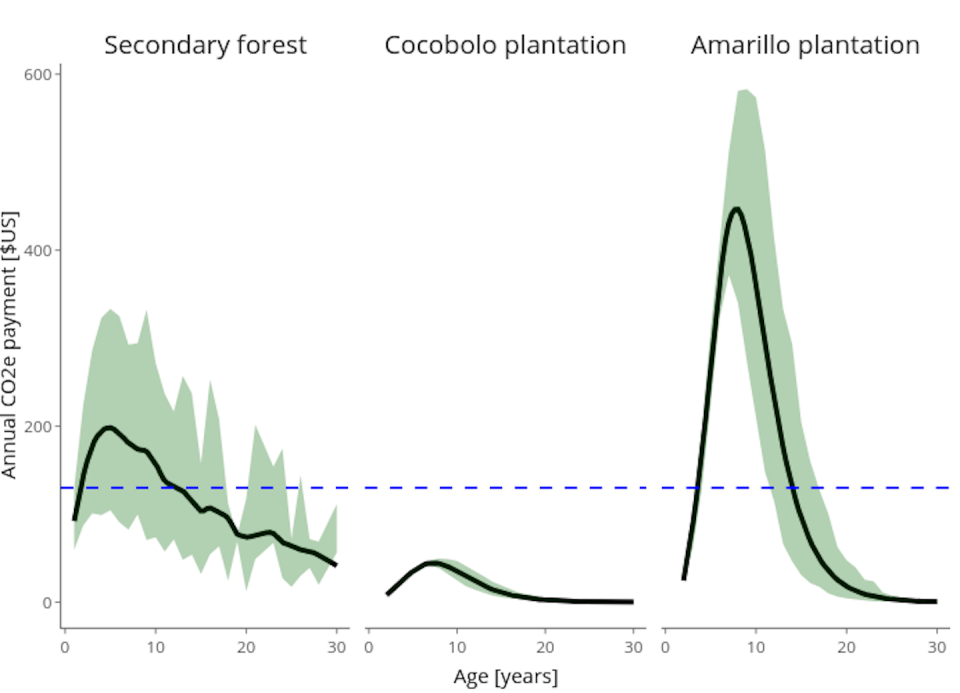

In our study, we used measurements of approximately 1.4 million trees taken over 15 years at the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute’s Agua Salud facility in Panama to estimate carbon sequestration and potential timber revenues. To test pathways to profitability, we examined an effort to rehabilitate a failing teak plantation by planting naturally regrowing forests, native tree species plantations, and high-value native trees known to grow on low-fertility soils.

A number of solutions have emerged: We have found that giving landowners the ability to both pay for carbon storage and generate income through timber production on the land can lead to living forests and financial gains for the landowner.

It may seem counterintuitive to recommend timber harvesting when the goal is to restore forests, but allowing landowners to earn timber revenue can incentivize them to preserve and manage planted forests over time.

Because trees take up large amounts of carbon from the atmosphere, regrowing trees on a deforested landscape, whether through natural regrowth or plantation, is a net win for climate change. New forests selectively cut down or fields harvested over 30 to 80 years could help slow climate change as the world reduces emissions and expands carbon capture technologies.

Secure payments are important

The structure of payments is also important. We find that reliable annual carbon payments to rural landowners for regrowing forests could match or exceed the income they could receive from clearing land for cattle, thus enabling a switch to growing trees.

When cash payments are based on tree growth measurements, they can vary widely from year to year and depending on planting strategies. Given the costs, this could pose a barrier to effective land management in combating climate change.

Using fixed annuities instead guarantees a stable income and helps encourage more landowners to sign up. We now use this method in Panama’s native Ngäbe-Buglé Comarca. The project pays residents to plant and nurture native trees for 20 years.

Shifting risk to carbon offset buyers

From a practical perspective, fixed annual carbon payments for planting trees and other cost-sharing strategies shift the burden of risk from participants to carbon sinks, mostly to companies in rich countries.

Even if the actual growth of trees is insufficient, landowners are paid and everyone benefits from the ecosystem services provided.

While win-win solutions may not initially seem economically efficient, our work helps show a workable path forward where environmental, social and economic goals can be met.

This article is republished from The Conversation, an independent, nonprofit news organization providing facts and authoritative analysis to help you understand our complex world. Written by: Jefferson S. Hall, Smithsonian Institution; Katherine Sinacore, Smithsonian Institutionand Michiel van Breugel, National University of Singapore

Read more:

Receives funding from the U.S. government through Jefferson S. Hall, the Smithsonian Institution, Stanly Motta, Frank and Kristin Levinson, the Hoch family, U-Trust, and the Mark and Rachel Rohr Foundation.

Katherine Sinacore receives funding from the Mark and Rachel Rohr Foundation, Stanly Motta, Frank and Kristin Levinson, the Hoch family, and the Smithsonian.

Michiel van Breugel receives funding from the Ministry of Education, Singapore and the ETH-Singapore Centre’s Future Cities Lab Global Programme, funded by the National Research Foundation of Singapore.