Traditional belief holds that the island of Rapa Nui, also known as Easter Island, once had a large population that collapsed after living beyond their means and destroying the island’s resources. A new research study that my colleagues and I conducted has dealt another blow to this notion by using artificial intelligence to analyze satellite data on rock piles on this small island in the middle of the Pacific Ocean.

Our study examined rock gardens, a form of subsistence agriculture, and determined that the island, which is just 15 miles (14.6 km) long and 7.6 miles (12.3 km) at its widest point, likely never held more than 3,000 or so people. European explorers encountered it in 1722.

The traditional belief arose from speculation about another set of stone structures on the island: iconic giant statues called moai, carved by the ancestors of the Rapanui people. The statues are as high as a three-story building and weigh up to 70 tons. There are about 1000 of these across the island.

For an archaeologist, the mystery of what caused people to spend so much time and energy building these colossal figures requires an explanation. My colleagues and I have been searching for one for the last 24 years.

Some of the first European visitors assumed that the island must have hosted a much larger population at one point to account for the number and size of the moai. This assumption is repeated over generations and forms the basis of the collapse narrative.

The story of the collapse suggests that the island once relied on tens of thousands of residents for the labor required to carve and move the colossal statues. Such a large population was not sustainable, and food shortages ultimately resulted in starvation, war, and even cannibalism. As a result the population fell to the meager numbers observed by early European explorers.

In our previous studies of the island, my colleagues and I asked ourselves the following question: Were there so many people living on the island before the arrival of Europeans, where is the evidence for this? We have launched a new study to examine whether such a large population is possible, given how the Rapanui people use rock gardens to grow much of their food. Our best guess, considering the available data, is that there were never more than 3,000 to 4,000 people on the island and that they lived sustainably.

What do rocks say about farming?

In this study, we examined the archaeological record of how the Rapanui used rock gardening to grow their main crop, sweet potatoes. Rock gardening is a form of cultivation in which broken pieces of bedrock are added to the soil to enrich the soil. There are extensive rock garden plantations throughout the island and these areas may provide a critical food source enriched by marine resources.

Previous studies have noted the size of these gardens and concluded that these efforts could support up to 16,000 people. However, our fieldwork revealed that many of the areas this study identified as rock gardens were misidentified. Therefore, we needed to do a more detailed analysis to get a better estimate of rock gardening; This would provide us with a more reliable source of information about maximum possible population sizes.

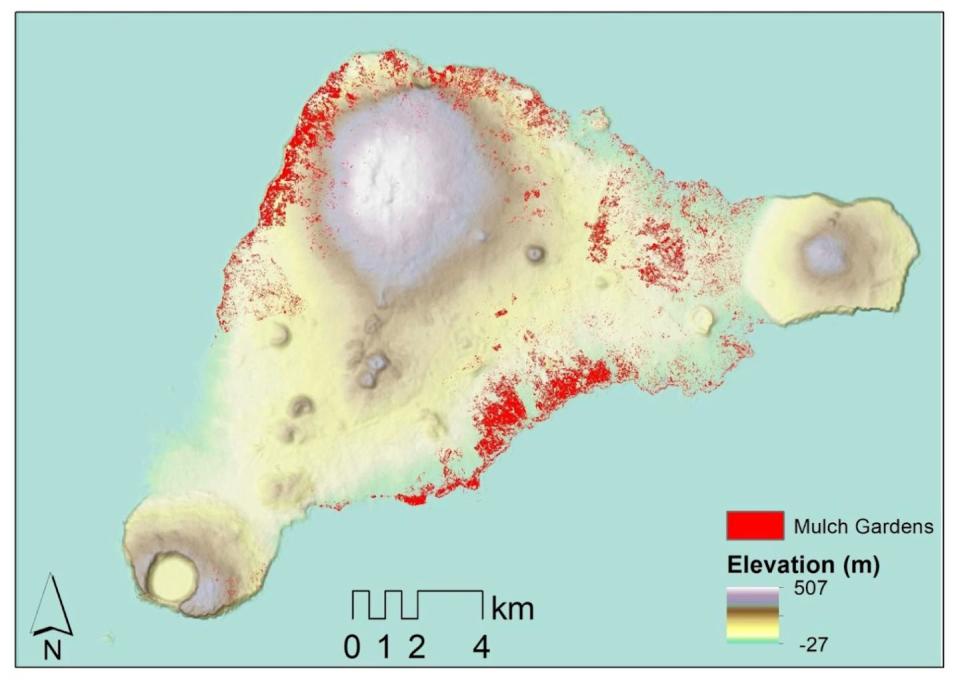

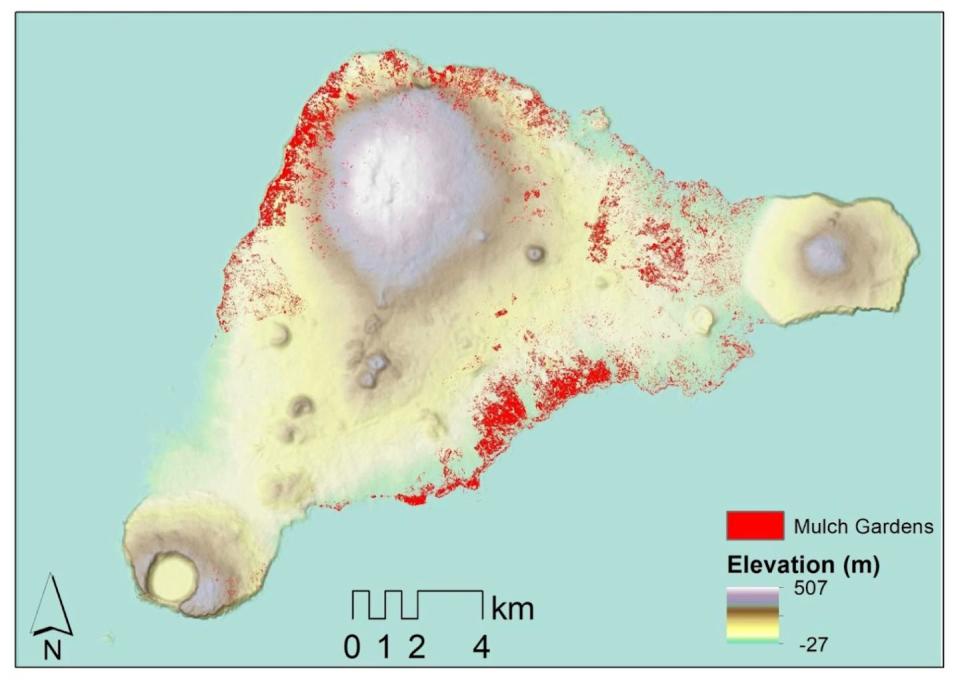

We combined field work with new satellite imagery analysis. During our fieldwork, we looked around the landscape to find clear examples of rock gardening. We knew we were in rock gardening areas when we found patches covered with rocks in places not easily explained as a result of erosion. Obsidian artifacts found among the rocks confirmed that these areas were used to cut and process sweet potatoes. Often there is another root crop, taro, which grows even today in these regions. We also identified sites that may resemble rock mulch gardens, but only with bedrock outcrops or randomly scattered pavers and boulders.

We then took WorldView-3 satellite images of the entire island. The WorldView-3 satellite collects imagery recording high-resolution visible light photographs and shortwave infrared information of the Earth’s surface. Shortwave infrared includes wavelengths ranging from 900 nm to 2,500 nm, longer than what the human eye can see. Shortwave infrared is useful in distinguishing materials that appear the same to the naked eye. Shortwave infrared in particular is sensitive to humidity differences, an important feature of productive agricultural areas.

Using our field data, we trained machine learning models to distinguish gardening areas with rock mulch from those without. Machine learning creates an algorithm that can detect subtle differences and do so repeatedly and systematically. In this way, we were able to survey almost the entire island quickly and without years of terrain mapping.

Our analyzes significantly reduced the total area of the island attributable to rock gardening from 1.6 to 8.1 square miles (4.3 to 21.1 square kilometers) to 0.29 square miles (0.76 square kilometers). When we went into estimates of the productivity of these areas, our calculations showed that the maximum number of people this type of cultivation could support was approximately 3,000; This is quite similar to the results we reach with other sources of information.

Endurance instead of arrogance

Over the past 20 years, researchers have obtained important new evidence about the archaeological record of Rapa Nui, contributing to reframe the island’s narrative away from the idea of collapse. For example, my team’s work shows that the statues were transported from the quarry to their final location by walking on platforms called ahu. We also addressed the question of how the islanders placed giant multi-toned hats called pukao on top of these statues.

However, the idea that there were many more people on the island continues to appear in academic and popular literature. Persistence with this idea has consequences beyond the field of Rapa Nui archaeology. Despite archaeological evidence to the contrary, it is not uncommon for ecologists, for example, to use Rapa Nui as a case study in so-called Malthusian demography; Here the population is assumed to have reached a peak so large that it momentarily outstripped the island’s resources, triggering an ecological disaster.

While my colleagues and I agree that there is a need to be concerned about the potential for exploitation of natural resources, catastrophe is not the only possibility. Human history offers many examples of how sustainable living can be possible despite constraints.

On Rapa Nui, we learned that its people did not experience a population collapse before the arrival of Europeans, but instead thrived because of their creativity. The Rapanui people found clever ways to adapt to the island and practice sustainable agriculture to support themselves. This research project adds details about the rock gardens’ capacity to grow food and support the island’s population.

Our increased understanding of the island has critical implications for the future. As society learns how to thrive in a limited environment, it may adopt strategies that people used in the past. The archaeological record of Rapa Nui points to the idea that efforts that brought communities together in cooperative and competitive ways, such as moai carving and transportation, led to greater resilience in times of shortage.

Ultimately, the history of Rapa Nui is not a cautionary tale, but a source of inspiration that may hold the key to humanity’s future.

This article is republished from The Conversation, an independent, nonprofit news organization providing facts and authoritative analysis to help you understand our complex world. Written by: Carl Lipo, Binghamton University, State University of New York

Read more:

Carl Lipo receives funding from the Lasting Impacts: Sustainability Archeology Program of the National Science Foundation and the National Geographic Society.