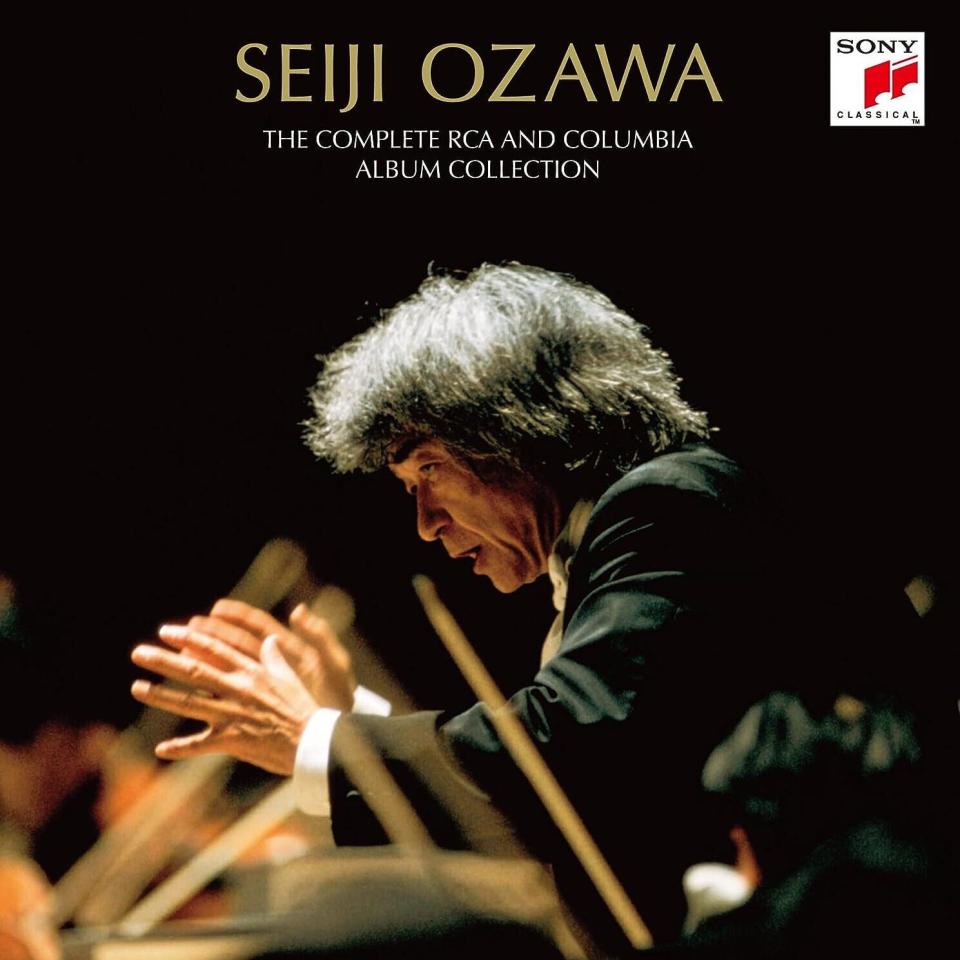

Seiji Ozawa, who has died at the age of 88, was one of the few Japanese musicians who left a significant mark on the Western classical music tradition. He crossed the East-West divide with remarkable ease, creating captivating music during his nearly three-decade tenure with the Boston Symphony Orchestra.

He was also a pioneer of classical music in an increasingly westernized Japan, showing his citizens that embracing European culture did not have to diminish their own traditions. Although other Japanese artists were well known in Western concert halls—among them Yo Yo Ma (cello), Mitsuko Uchida (piano), and Midori (violin)—Ozawa was their unelected leader, blazing a trail in Europe and America.

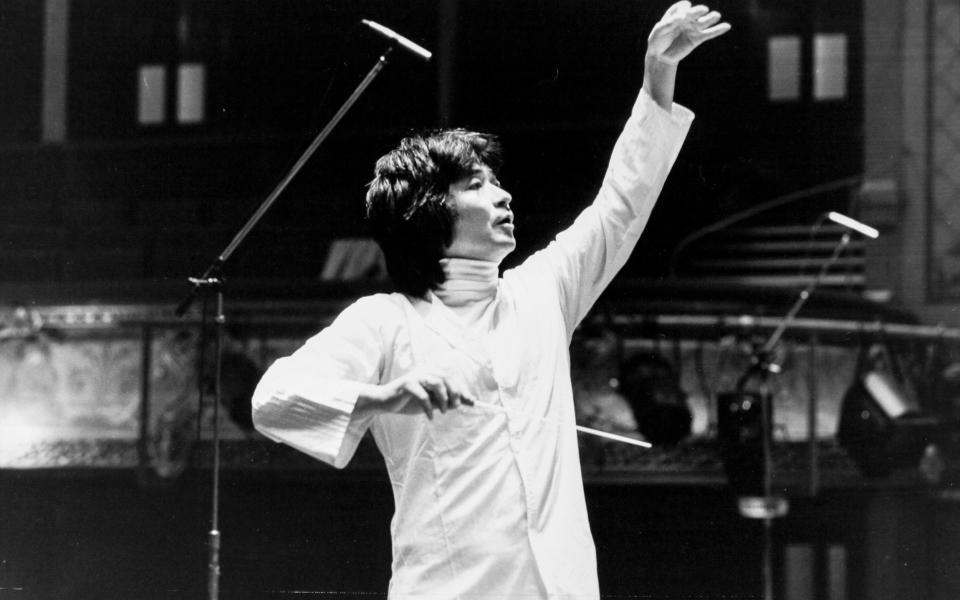

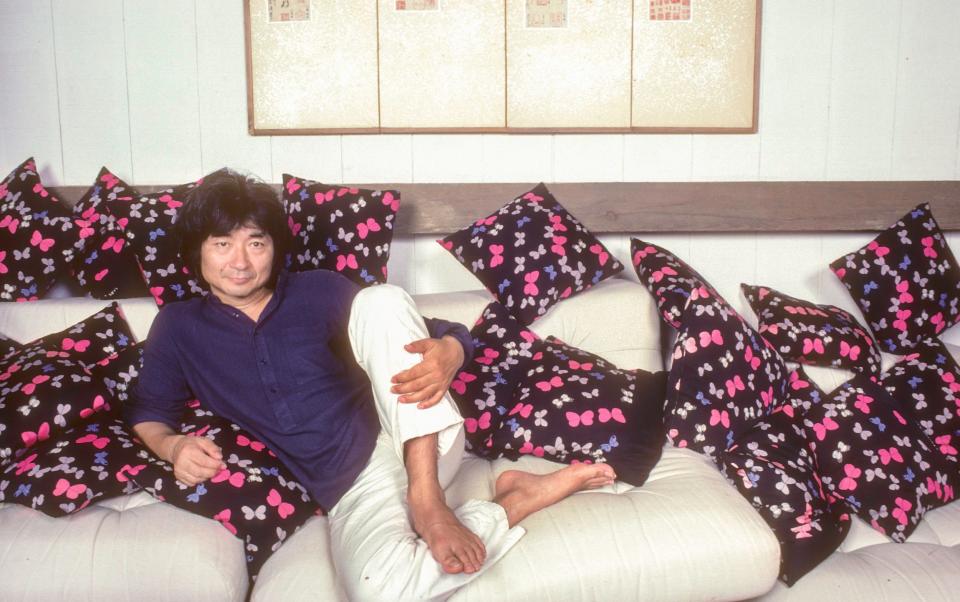

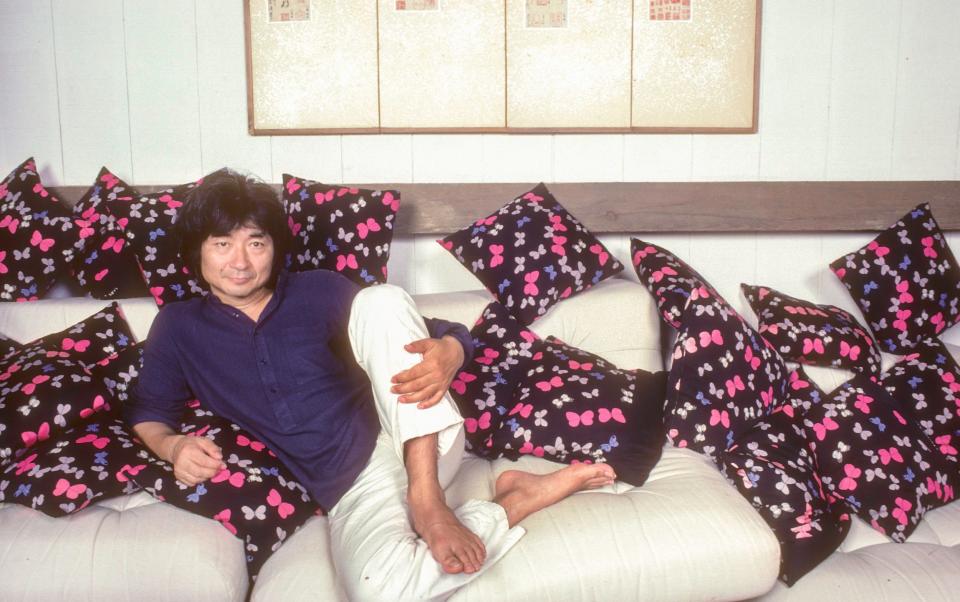

The appointment of a successful Asian to Massachusetts – he was then holding a similar post in San Francisco – coincided with a growing fascination with all things Oriental in the United States and rising anti-Vietnam War sentiment. Ozawa, a Boston Red Sox fan, played the gallery on the runway wearing a turtleneck sweater instead of a dinner jacket and, at first, a Beatles-style fringe.

After decades of aging European conductors dominating North American music, Ozawa was explosive and energizing, surprising to some and fiery to others. He enlivened concert halls, enlivened orchestras and inspired audiences with his electrically crackling performances.

At the same time, however, he became the epitome of the itinerant, rootless, bicoastal conductor who, instead of embedding himself in an ensemble, spent as much time in airport lounges as concert halls, flying there to rehearse, conduct and collect his paycheck. There were those who questioned whether there was actually much substance beneath the flashiness.

He was equally well-known in Europe, where his charismatic figure made a huge impact in concert halls in London and Berlin. His very presence in the audience can create excitement among the orchestra players on the podium. The scarcity of Japanese representatives among Western musicians has caused him to be frequently associated with his compatriot, the composer Toru Takemitsu; both made a significant impact in London at the 1991 Japanese Festival.

On his return to Japan, he conducted five symphonies for the Winter Olympics in Nagano in 1998; these included conducting choirs on five continents simultaneously (via satellite) in the finale of Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony.

He danced lightly as he managed on the platform, leaning back and waving his baton into the air. As he got older, his hair became messier and his demeanor seemed more relaxed; His English was barely sufficient for a television interview.

He claimed that his Japanese roots were a benefit rather than a hindrance in the fight against Western classical music. “It is very difficult for a French conductor to enter the German tradition,” he once said. “But we Japanese can get good musical traditions from all countries because we have no traditions of our own.”

Seiji Ozawa was born on September 1, 1935, in Hoten, China, then in Japanese-occupied Manchuria. His father was a dentist and was said to have once hauled a piano 25 miles in a wagon so his son could have an instrument to play. His mother raised the family as Christians and his older brother became a church organist.

By the age of seven and now living in Japan, his interest had turned to Western music. He came under the influence of Hideo Saito, a German-educated musician related to his mother who was almost single-handedly responsible for expanding the influence of Western music in occupied post-war Japan. In his book The Maestro Myth, Commentator Norman Lebrecht describes how young Seiji, unable to afford his teacher’s fees, “spent seven Jacobean years as a servant in Saito’s household.”

At 16 he entered the Toho School in Tokyo hoping to become a pianist, but his ambitions were dashed when he broke both his index fingers on the rugby field. Instead he turned his attention to conducting. His first encounter with the Boston players came during his student days during a post-war tour of Japan. But despite Saito and his influence, Ozawa had never heard a live opera performance or Mahler symphony until he was 23.

He reached Europe by cargo ship in 1959 and earned his living by working as a motorcycle sales representative for a Japanese company. He soon saw an advertisement for a conducting competition in Besançon: He entered the French town on a Japanese motorbike, entered the competition and won; In the process, he endeared himself to the esteemed master Charles Munch, who was on the jury.

Before long – and despite knowing almost no English – he visited Tanglewood, Massachusetts, where he received the Koussevitzky Prize. He soon returned to Europe and studied under Herbert von Karajan in Berlin. Leonard Bernstein saw him there and invited the young conductor to become his assistant at the New York Philharmonic, where he served from 1961 to 1965; During this time, he appeared on US television, as if to underline his popular credentials. show What is My Line? He also served as artistic director of the Ravinia Festival in Chicago.

Ozawa served as music director of the Toronto Symphony Orchestra (1965-69), with whom he got his first real taste of international touring. But his big break in the United States came when Dmitri Shostakovich, who was scheduled to conduct in San Francisco, fell victim to Cold War politics, and the West Coast orchestra was in dire need of a replacement.

The Californians appointed him music director in 1970, but his goal was always Boston and Koussevitzky’s mighty legacy. He was appointed music director there in 1973, but controversially chose not to give up his West Coast post for another three years, leading to accusations of absenteeism on both coasts.

Although there were many good times in Boston—notably the orchestra’s centennial world tour in 1981 and the construction of Seiji Ozawa Concert Hall in Tanglewood in 1994—when the novelty of both the maestro and the turtleneck wore off, Ozawa dug in his heels and declined. Continue on your way, determined to become the orchestra’s longest-serving conductor.

A group of BSO players published a circular in which they expressed their open hostility. Commenting on his frequent insistence that the relationship between a conductor and his orchestra is akin to a marriage, they said that “not all marriages end in death… some marriages continue monotonously with a lack of mutual respect, respect and encouragement.” .” Professional critics also declared him unwelcome. The Boston Globe’s respected critic Richard Dyer was among those who said Ozawa failed to deliver on his youthful promise.

But 28 years later, he moved on. In 2002 he found himself in Europe, where he followed in von Karajan’s footsteps as principal conductor of the Vienna State Opera (he began the year by conducting the traditional New Year’s concert with the Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra, the recording of which became Japan’s record). fastest selling classical record). He conducted Mstislav Rostropovich’s final cello performance in the Austrian capital, the premiere of a new work by Polish composer Krzysztof Penderecki.

Following the excitement in America, Ozawa’s eagerly awaited London debut came in 1965, with an LSO program of Beethoven, Berlioz and Mozart to a wary but welcoming response from critics: The Times noted that it “justified expectations up to a point” “.

He became a frequent visitor to Britain with the Boston Symphony Orchestra at the Edinburgh Festival, particularly during John Drummond’s tenure (his 1979 concerts have been described as “taking ideas of orchestral interpretation into a new league”). The relationship continued with Drummond moving to the Proms, including a memorable evening with Jessye Norman at the Royal Albert Hall in 1984.

Incidentally, he was first seen conducting at Covent Garden in Eugene Onegin in 1974, and was a frequent guest conductor of the Philharmonic in the 1980s. He also directed Kiri te Kanawa’s first Tosca in Paris in 1982.

Ozawa canceled all his appointments in 2010 after doctors diagnosed him with esophageal cancer. Immediately after successful surgery, he developed chronic sciatica, making it nearly impossible for him to spend more than five minutes on the podium.

Ozawa, who maintained ties with Japan despite his travels, founded the Saito Kinen Orchestra in 1984 in memory of his teacher who visited the Proms in 1990, and the Saito Kinen Festival in the “Japanese Alps” in Matsumoto, taking Tanglewood as an example. He held a series of six conversations about classical music with novelist Haruki Murakami, resulting in his 2016 book Strictly On Music.

His first marriage was to pianist Kyoko Edo. He rented a house in Tokyo with his second wife, Vera Ilyan, and their daughter and son.

Seiji Ozawa was born on September 1, 1935, died on February 6, 2024.