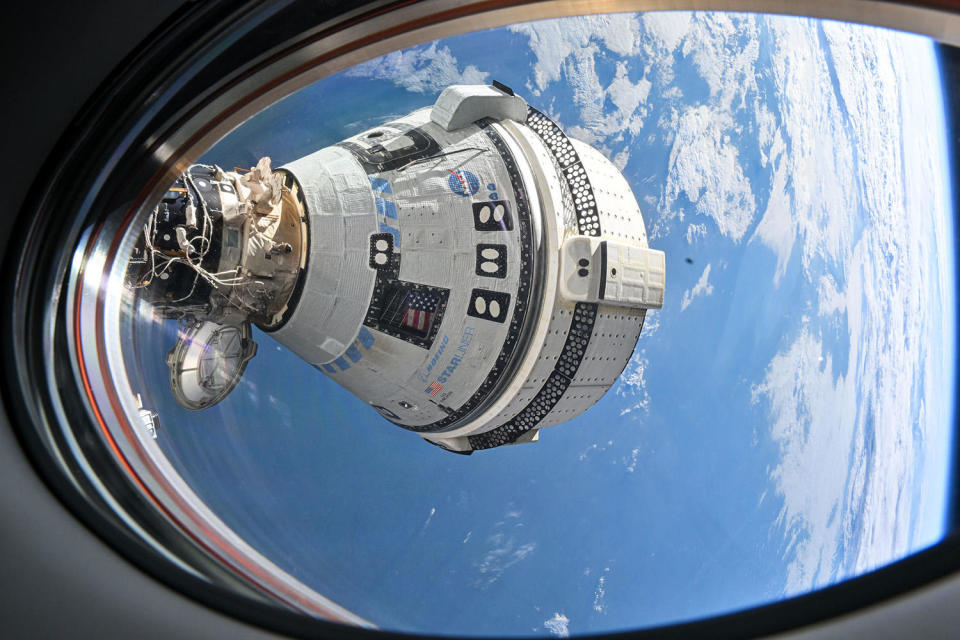

Boeing’s troubled Starliner spacecraft — not trusted by NASA to bring its crew home safely from the International Space Station — equipped to leave Friday and a pilotless return to Earth to end a disappointing journey test flight It was damaged by helium leaks and thruster problems.

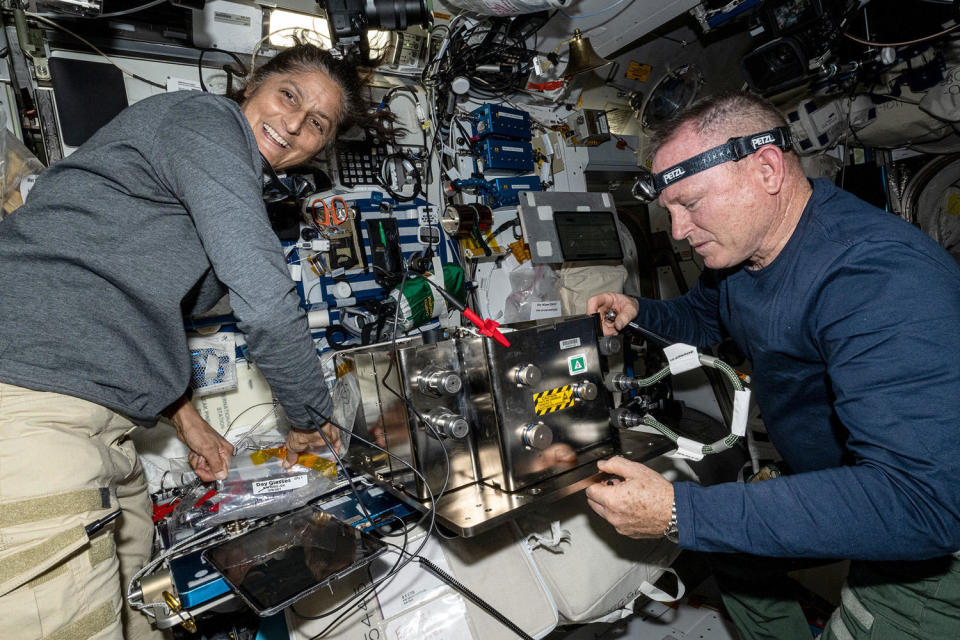

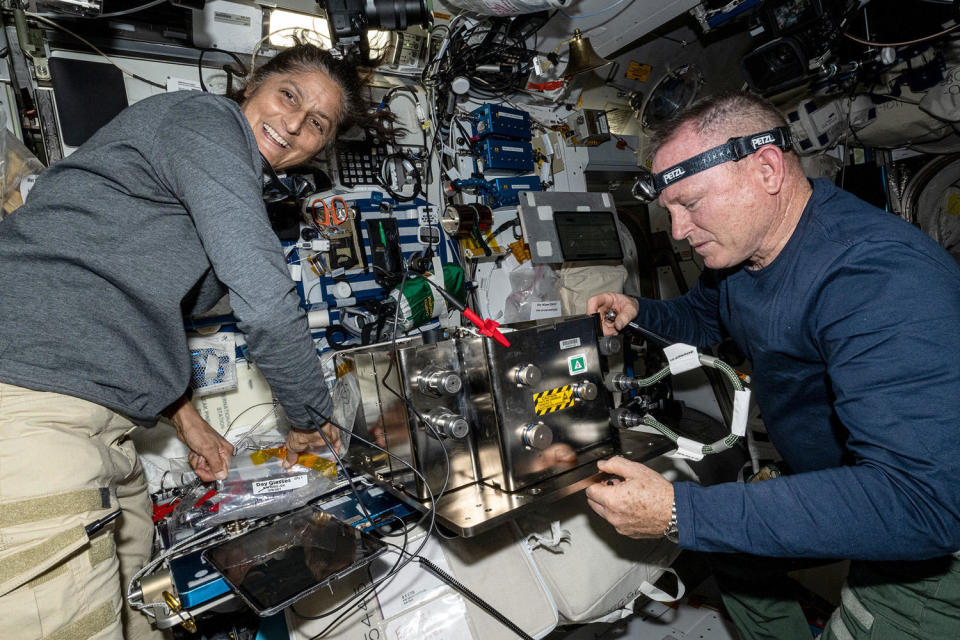

The Boeing spacecraft, leaving behind Starliner commander Barry “Butch” Wilmore and pilot Sunita Williams, is expected to depart from the station’s forward dock at 18:04 GMT.

Moving over the station to a point far behind and above the laboratory complex, Starliner’s braking rockets were expected to fire at 11:17 p.m., knocking the craft out of orbit and beginning a fiery re-entry dive for a landing at White Sands, New Mexico, just after midnight Eastern Time.

Despite the test data convincing Boeing engineers and managers that Starliner could bring its crew home safely despite earlier problems, NASA managers concluded that sufficient uncertainty remained. Keeping Wilmore and Williams at the station and sinking their ships by remote control.

Astronauts will stay in space until February

The two astronauts will remain at the space station until the end of February. go on a trip The SpaceX Crew Dragon spacecraft, set to launch on September 24, is expected to carry long-term crew to the laboratory.

Crew Dragon normally launches with four crew members, but two NASA astronauts were removed from the upcoming Crew 9 flight to free up seats for Wilmore and Williams. They will join Crew 9 commander Nick Hague and Russian cosmonaut Alexander Gorbunov for their normal six-month tour of duty.

When Wilmore and Williams return to Earth around Feb. 22, they had planned to spend about eight days in orbit, but they will have spent more than eight and a half months in space.

NASA astronaut Frank Rubio faced a similar dilemma during his six-month stay aboard the station in 2022. extended for more than a year Due to problems with the Russian Soyuz spacecraft that carried him into orbit.

“I think going from six months to 12 months is tough, but not as tough as going from eight days to eight months,” Rubio told CBS News. When asked how Wilmore and Williams were taking the news of the extension, he said, “They’re doing very well.”

“Sure, there’s a little part of you that’s frustrated,” he added. “It’s OK to admit that. But you also can’t sulk the whole time, right? … You just have to dedicate and re-dedicate yourself to the task.”

A series of setbacks for Boeing

The decision to ground Starliner without a crew was a devastating blow to Boeing, where previous problems had delayed Starliner’s first piloted flight by nearly four years, required a second unpiloted test flight and cost the company more than $1.5 billion on top of its fixed-price contract with NASA.

Starliner troubles are also a plus Boeing’s The ongoing struggle to restore public trust following two incidents 737 Max 8 plane crashedwith a close call Alaska Airlines 737 flight suffering door plug explosion Problems earlier this year and more recently with an upgraded version of the company’s long-haul 777 aircraft.

It is not yet known what needs to be done to fix the problems encountered on the last Starliner flight, whether another costly test flight will be required or when the craft could be ready for active service to ferry astronauts to and from the station.

The station crew closed the Starliner’s hatch at 1:29 a.m. Thursday. Williams described the moment as “bittersweet” as they worked to arrange items returned the day before to ensure proper balance and center of gravity inside the Starliner.

“Thank you for supporting us, thank you for looking out for us and making sure everything is in the right place,” he told the flight controllers. “We want it to have a nice, soft landing in the desert.”

After a final check of the weather conditions at the New Mexico landing site, the hooks on the Starliner’s docking mechanism were expected to release and the station-side springs were expected to push the crewless ferry away.

A series of thruster fires were planned to gently push the spacecraft past the front of the laboratory complex, then go up and separate toward the back. Seven minutes after separation, Starliner was expected to exit a 1,300-foot-wide safety zone known as the “stay-away sphere.”

Given the earlier thruster issues, NASA shortened the launch timeline to get Starliner away from the station as quickly as possible. Sixteen minutes after leaving the standoff sphere, the spacecraft was expected to exit the larger “approach ellipsoid,” another safety zone around the ISS that is 2.5 miles long and 1.2 miles wide.

The ship’s flight computers were programmed to guide the spacecraft toward a specific point where braking rockets could be fired to slow the craft, knock it out of orbit, and set it on course for a nighttime landing at White Sands.

To deorbit, four large orbital maneuvering and attitude control rockets (OMACs) had to be fired for 59 seconds, slowing the craft’s 17,100 mph speed to about 300 mph, enough to lower the far side of the orbiter into the atmosphere and re-enter and land at the New Mexico landing site.

While the powerful OMAC braking rockets were firing, smaller reaction control system (RCS) jets were expected to fire under computer command to keep the Starliner balanced and pointed in the right direction.

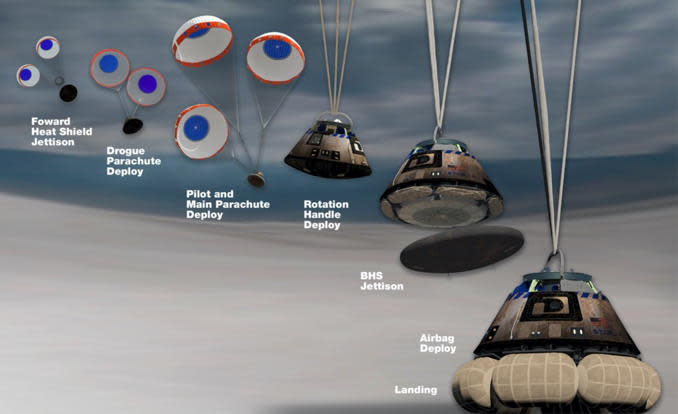

Once the orbital rocket has completed its ignition, the Starliner’s service module, which houses the OMACs, 28 RCS jets, helium tanks and other critical systems that are no longer needed, will be ejected into the atmosphere and burned.

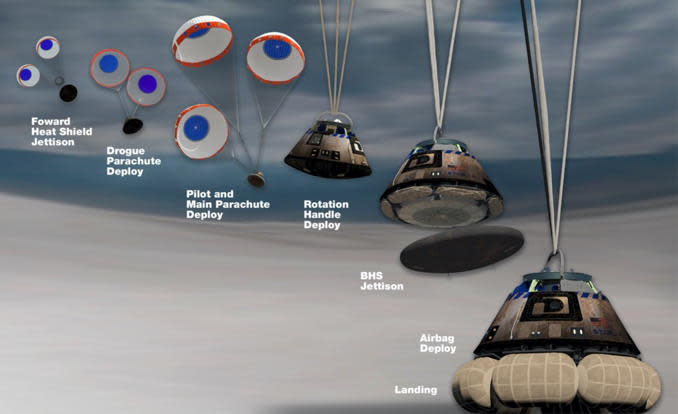

The crew module, protected by a heat shield and equipped with 12 RCS jets, will then begin its re-entry by descending back into the atmosphere at an altitude of approximately 400,000 feet, enduring temperatures of up to 3,000 degrees Fahrenheit, and traveling at a speed of about five miles per second.

The southwest to northeast re-entry trajectory will take Starliner over the Baja Peninsula, the Gulf of California, northern Mexico and New Mexico.

At about 24,500 feet, two small drogue parachutes will deploy, slowing and stabilizing the Starliner. About a minute later, at 8,000 feet, three pilot parachutes will deploy the craft’s three 104-foot-wide main parachutes, slowing the descent to about 18 mph.

At an altitude of 2,500 feet, the airbags will inflate, reducing landing impact forces to a level equivalent to walking speed. Landing is expected to occur one minute after midnight EDT (10:01 p.m. Friday local time).

The deorbit burn and computer-regulated attitude control system firings are critical to deorbiting at the precise trajectory needed for a precision landing. And all of these firings require pressurized helium to propel the thrusters to healthy thrusters.

During Starliner’s June 6 rendezvous with the space station the day after launch, five RCS jets were “deselected” by the flight computer due to degraded thrust. Additionally, four helium leaks were detected in the thrust pressurization system, adding to a small leak detected before launch.

After extensive testing and analysis, Boeing engineers concluded that the helium leaks were the result of slightly deteriorated seals exposed to toxic propellants for extended periods of time. But despite the leaks, Starliner still carries 10 times more helium than it needs to deorbit, they said.

Tests showed that the thrust problem was caused by high temperatures, which resulted in the Teflon seals in the poppet valves deforming and restricting fuel flow.

Engineers concluded that the high temperatures were largely the result of manual flight control tests that caused the jets to rapid-fire hundreds of times while the aircraft was positioned in direct sunlight for extended periods.

Test firings later in the mission showed the jets were functioning normally, indicating that the seals had returned to their original shape or a shape close to their original shape.

Boeing argued that there would be no manual flight tests for the piloted return to Earth, that the vehicle would be oriented to minimize solar heat on the suspect jets and that fewer ignitions would be needed in the absence of a rendezvous point.

Boeing tried to convince its NASA counterparts that Starliner had sufficient margin to bring Wilmore and Williams back to Earth safely.

But NASA managers did not accept Boeing’s “flight justification” and chose to crash the Starliner without a crew.

“Space flight is tough. The margins are tight. The space environment is unforgiving,” said Norm Knight, director of flight operations at the Johnson Space Center. “And we have to be right.”

Israeli West Bank operations. What we know.

Harris campaign nearly triples Trump’s fundraising numbers in August

Jobs report weighs on stocks as rate cut likely