A young couple poses in their shiny new Cadillac on West 127th Street in Harlem. The woman wears a cloche hat and, with a slight smile, offers a cold gaze from under the wide brim of the fedora. They both wear flamboyant ankle-length raccoon coats.

James Van Der Zee’s 1932 photograph “Couple” is among the 160 paintings, sculptures, photographs, films and ephemera in the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s comprehensive exhibition “Harlem Renaissance and Transatlantic Modernism”, which opens on February 25 and runs through July It is among. 28.

More from WWD

The exhibition is a comprehensive and long-overdue chronicle of the ways Black artists interpreted and depicted everyday life in Harlem from the 1920s to the 1940s, during the early decades of the Great Migration, when millions of African Americans left the segregated rural South for New York . York, Chicago and other cities.

It was the dawn of the Jazz Age, with its flapper dress and Zoot suit aesthetic, and as made clear in Van Der Zee’s “The Couple,” fashion was integral to communicating the prosperity and humanity of Black Americans and countering decades of racist portrayals. from newspaper cartoons to minstrel shows and vaudeville theatre.

“In this moment in American history, fashion, the act of dressing up, was central to creating a new scenario for people of color,” says Jessica Lynne, author, art critic, and host of The Met’s “Harlem Is Everywhere” podcast.

Lynne adds that the dominant narrative, in terms of visual depictions and cultural outputs, suggests that Black people are “submissive.”

“They were often depicted wearing tattered clothing or clothing that indicated a particular class position or occupation, such as a servant or sharecropper. So James Van Der Zee’s beautiful photograph of this couple in Harlem, neatly dressed, is very much an offering of honor. And a lot of people weren’t used to thinking about Black people that way,” he says.

“It is also important to say that, of course, Black people knew that our dignity was inherent and inevitable and not something to be earned. But the gesture and presentation on a public stage truly restates a claim to dignity, especially for non-Black people. And it was certainly a very radical stance.”

Van Der Zee was the most successful portrait photographer working in Harlem at the time. The Upper Manhattan neighborhood was the center of Black culture, and cosmopolitan urbanites flocked to Garanti Photography Studio (which he founded with his wife Gaynella Greenlee) in their best clothes. His studio was filled with elaborate backdrop props: ornate tapestries and blankets, intricately carved scarecrows and mantles. Historian Bridget R Cooks says her studio in the department became “a theater of self-representation”.

Van Der Zee also visited homes, schools and churches to document personal milestones, including baptisms and weddings. In all these encounters, clothing was integral to conveying prosperity, comfort, and status.

Clothing was also of central importance to painters of the period, especially in the works of Laura Wheeler Waring, Archibald J. Motley Jr., William H. Johnson, and Palmer Hayden.

In 1944, Wheeler Waring, who had a talent for depicting the inner lives of his models, depicted singer and civil rights activist Marian Anderson wearing a vibrant red off-the-shoulder dress with bell sleeves and train, her nails painted to match her dress. , emphasizing the pensive position of his hands.

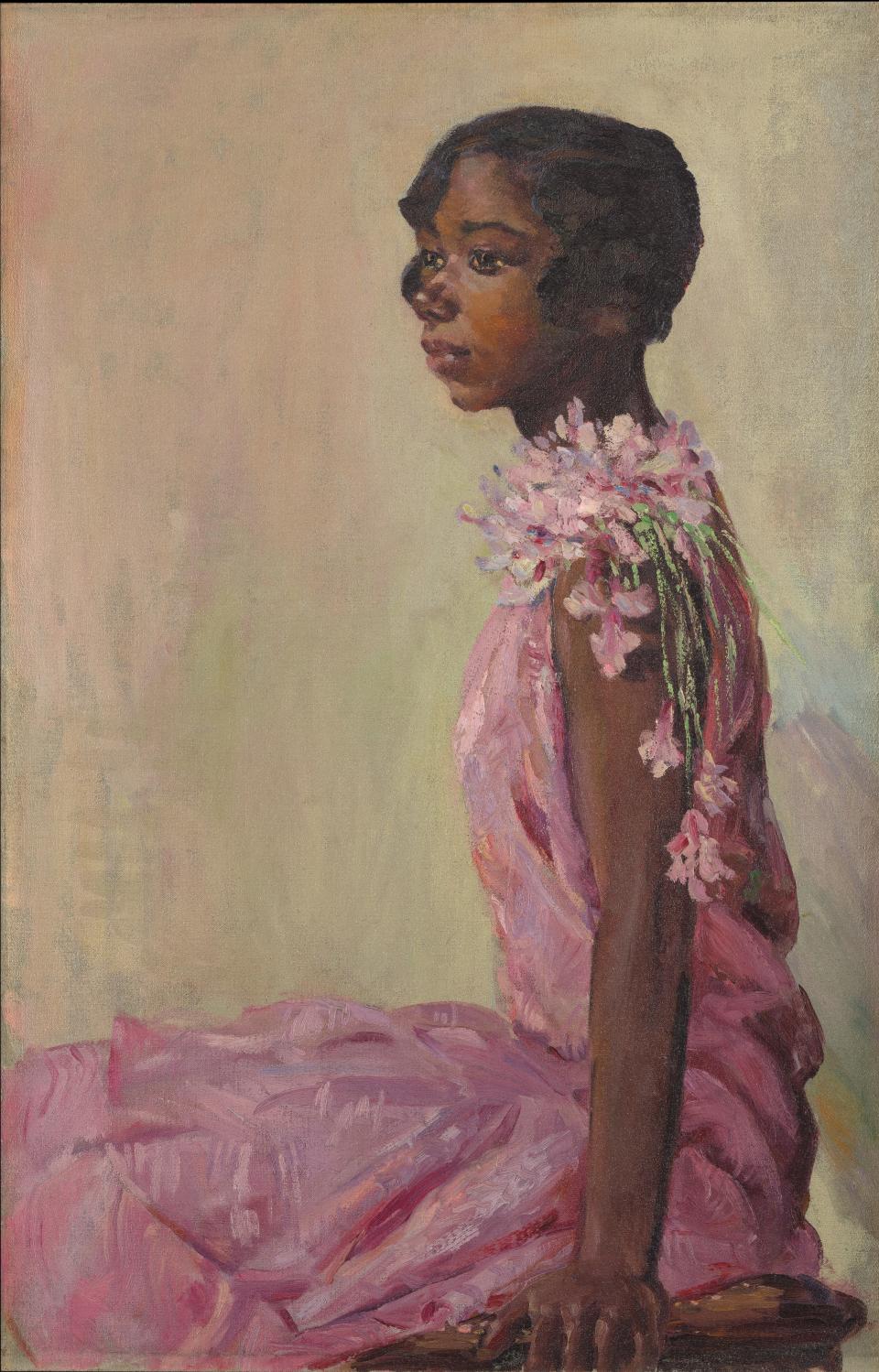

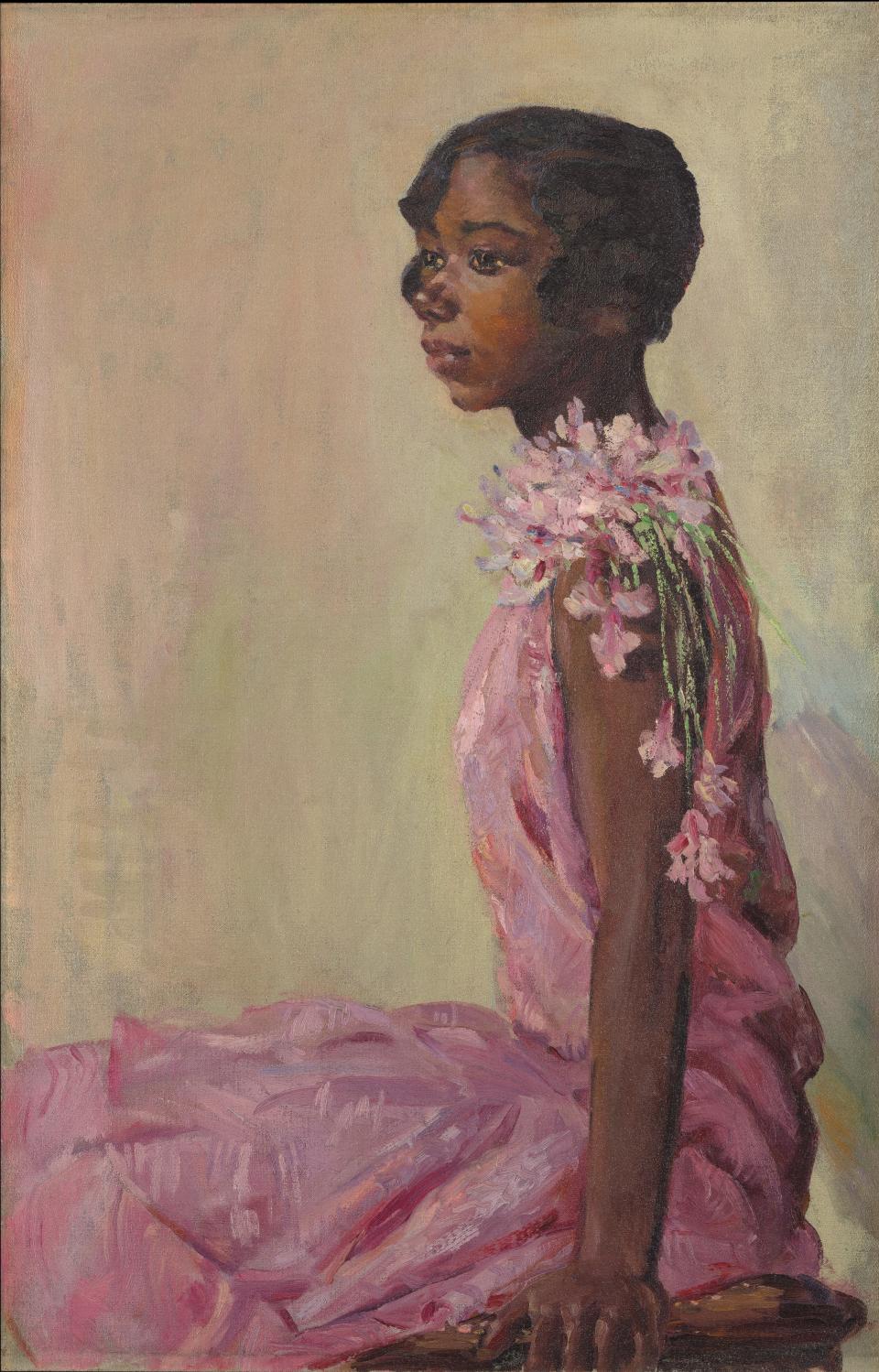

In “The Girl in the Pink Dress (ca. 1927),” the young sitter wears a flamboyant chiffon dress decorated with pink and white flowers from her left shoulder down, and in “The Girl with the Pomegranate (ca. 1940),” the sitter’s oversized white cut-out collar seems to direct the viewer’s gaze to her face. Like, placed on a soft brown dress.

“There is a deep respect and respect for the individual,” says Lynne. “The tremendous depth of how seriously they take their caregivers, regardless of their name, regardless of their position, which for me is the real gift here, is that I think so many people can be cared for with such beauty and seriousness and have their lives recorded.” it somehow held up against other types of images coming from other types of media at the same time.

Of course, clothing was also used symbolically to highlight the inequality that pervaded the era. Hayden’s painting “Dame of Harlem” (ca. 1930) depicts an elderly woman in a blue evening dress and pearls, with white stockings and shoes, sitting in her living room with her dog at her feet. But in the exhibition catalogue, Cooks notes: “Although she adopts the demeanor of a successful woman and possesses traditional attributes of privilege and leisure, she remains bound by Eurocentric restrictions that affect her daily life, such as her garish light-toned clothing.” The sock was likely promoted to white consumers as a ‘natural skin tone’ by manufacturers at the time who did not produce the product in shades that would suit Black women’s skin tones.

These juxtapositions are explored in the “Fashion and Portraiture” episode of the five-part podcast (available on any podcast streaming service), which features Cooks and Washington Post fashion critic Robin Givhan in conversation with Lynne. The first two episodes will air on February 20, followed by subsequent episodes focusing on “Arts and Literature” (March 5), “Music and Nightlife” (March 12), and “Civil Rights at their Peak” (March 19).

A significant portion of the paintings, sculptures, and works on paper in the exhibition are on loan from Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCUs), including the Clark Atlanta University Museum of Art, Fisk University Galleries, the Hampton University Museum of Art, and the Howard University Art Gallery. The exhibition comes more than half a century after The Met’s controversial 1969 exhibition “Harlem on My Mind.”: The Cultural Capital of Black America, 1900–1968, which sparked howls of protest because of its predominance of newspaper clippings and photographs of black leaders and prominent Harlem residents rather than the work of black artists. Since then, The Met has significantly expanded works by Black artists during the Harlem Renaissance, including paintings by Aaron Douglas, Elizabeth Catlett, and Charles Alston. In 2021, the museum established the James Van Der Zee Archive in partnership with the Studio Museum in Harlem.

“Our public relationship with society and consumption is quite different now,” says Lynne.

Works created by black artists during the Harlem Renaissance “realize as images of death” [of Black people] they are wandering around. White communities send postcards of lynchings and mutilations [Black] bodies. And so the juxtaposition of these very sensitive, thoughtful representations and depictions offers a contrasting assessment. These works do not appear suddenly. They live within a set of discourses, attitudes and expectations. “And when you think about that, that’s when you really understand the intervention that these artists are undertaking.”

The best of WWD