It’s dangerous territory, death duties – as new Chancellor of the Exchequer Rachel Reeves will find out if she decides to wade into this political minefield to get more taxpayers’ money.

Jean-Baptiste Colbert, Louis XIV’s finance minister, said: “The art of taxation is to pluck the goose in such a way as to obtain the greatest possible number of feathers with the least possible hiss.”

No matter how Reeves approaches it, dealing with inheritance tax is guaranteed to cause a particularly loud hissing outburst. Yet it is one of the sources of government revenue that the new Chancellor refuses to tie his hands with, making him the most likely favourite to pull it off.

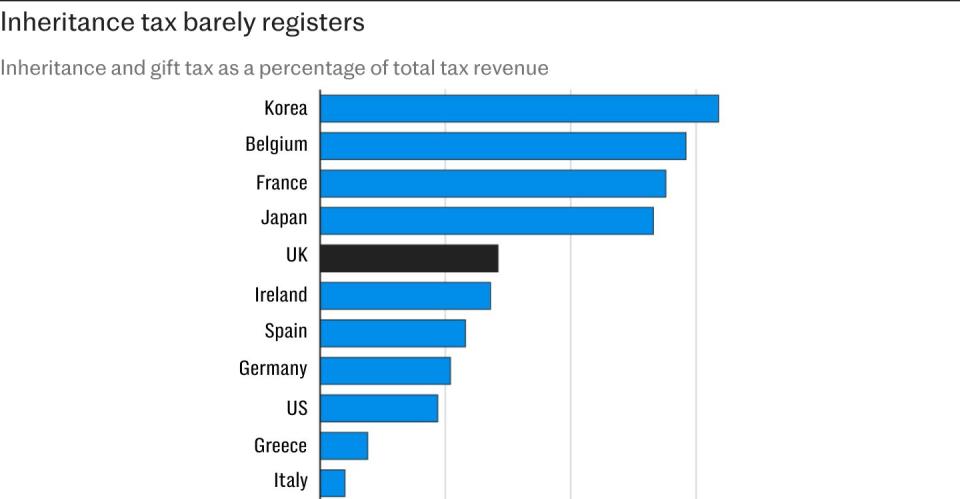

At this very moment, the left-wing think tank Demos has come out with a 65-page report on inheritance tax reform, which says that all but one of the G7 economies receive far more income from death duties than we do in the UK.

The only exception is Italy, where the tax rate is extremely low and only applies to properties worth over €1 million (£840,000).

All the others, including the US, manage to get more than the UK, where only 4.2% of transferred wealth was paid in tax in the 2019/20 tax year. Inheritance tax, at just 0.7% of government revenue, is barely recorded.

For Reeves, the temptation must be irresistible. If we adopted the same system as South Korea, for example, the Treasury could collect £6.5bn more a year in inheritance tax than it currently does, according to Demos, and a further £2.5bn if we adopted the same approach to lifetime wealth transfers.

Reform is made all the more attractive because inheritance tax is so widely seen as unfair as it is. It is almost entirely avoidable for the very rich, but for middle England, where the tax is increasingly caught up in rising property prices, it is almost impossible to avoid.

But just because it’s considered unfair doesn’t mean it’s easy to reform. For example, there are good reasons for exemptions on alienated businesses and farmland, and not just because family businesses and farms are businesses you want to encourage.

Much of the German economy is built around a medium-sized structure of small to medium-sized, family-run businesses that are passed down from one generation to the next. I wish we had something like that in the UK.

Imposing a death duty on such businesses could put them in danger of disintegration or making them commercially unviable. The same applies to farms, which could become uneconomic if they were forced to sell land to pay inheritance duty.

Some farmers have been caught up in government-backed rewilding schemes and are finding that rewilded land is no longer exempt from inheritance tax.

The broader implication of death taxes is that they attack something deep within the human soul: the desire to accumulate the fruits of one’s labor or good fortune and pass them on to one’s children or chosen causes.

It’s in our DNA, and no amount of political moralizing or social engineering can make it go away. Death taxes are, pure and simple, a tax on desire. They’re also a form of double taxation, in that in most cases they’re applied to money that’s already been taxed.

Oddly enough, you might think that this is one of those taxes that many people think they might have to pay, but a relatively small percentage of properties actually do. So raising the level at which the tax becomes payable tends to be politically popular, even if only a few people benefit from it.

Conversely, if Reeves tries to lower the threshold, he will undoubtedly lose votes; many more people will think he is being held more accountable than he actually is.

Former Chancellor of the Exchequer Ken Clarke said that he abandoned tax reform when he realised that no matter what he did, it would create winners and losers, that he would be punished politically by the losers and would get no credit from the winners.

Reeves may be about to learn this lesson the hard way about inheritance taxes, and despite the financial pressures to collect more taxes, he would do well to tread carefully.

There is no doubt that the current British system is a terrible tax. As Chris Sanger, head of tax policy at EY, put it: “If you’re designing a system from scratch, you don’t start here.”

The simplest solution would be to abolish the tax altogether, which was the ultimate intention of the last Conservative government, but that is clearly not going to happen under Labour.

There are some jurisdictions, such as Singapore, that have never imposed this tax, but outside of low-tax havens like this thriving city-state, it is difficult to find an economy that does not impose an inheritance tax of any kind.

It is true that there is no inheritance tax in Canada, Australia and Norway, but in all three jurisdictions recipients of inherited wealth are subject to capital gains tax when they inherit or dispose of assets. These could reasonably be seen as the same thing.

It is also true that most OECD countries tax receipts rather than inheritances. This has always seemed to me to be a better approach structurally. But what all these systems have in common is that they are incredibly complex, subject to quirks, and widely perceived as unfair.

But some are more progressive than others; Labour’s redistributive goals will undoubtedly also drive a redesign of the British system; the government could also combine this with some form of permanent wealth tax.

If Reeves were truly radical, he could replace the inheritance tax with a lifetime wealth tax.

Whatever he does, he must first understand that all wealth taxes generally have very harmful behavioral consequences. Surprise — they tend not to be at all conducive to wealth creation, growth, and hence ultimately to the growth of the tax base.

We are already seeing some of these results with the proposal to remove tax breaks for non-doms. Many non-doms vote with their feet. The same will be true for inheritance tax. If you put too much pressure on wealth, wealth will go somewhere else.

In today’s world, capital is very mobile; in Colbert’s day, it was hard enough to pluck feathers with minimal hissing. Today, it’s even harder.