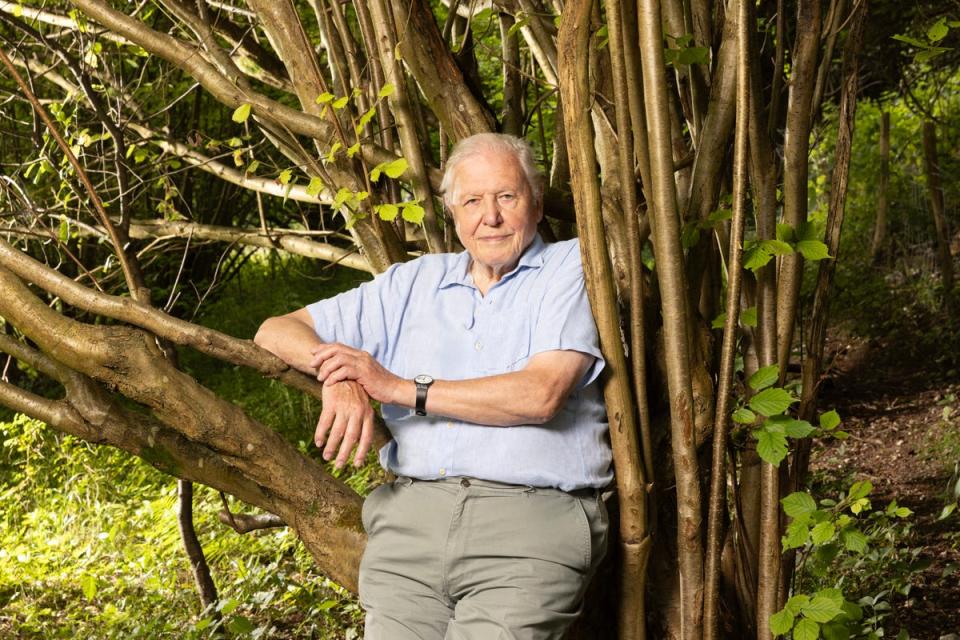

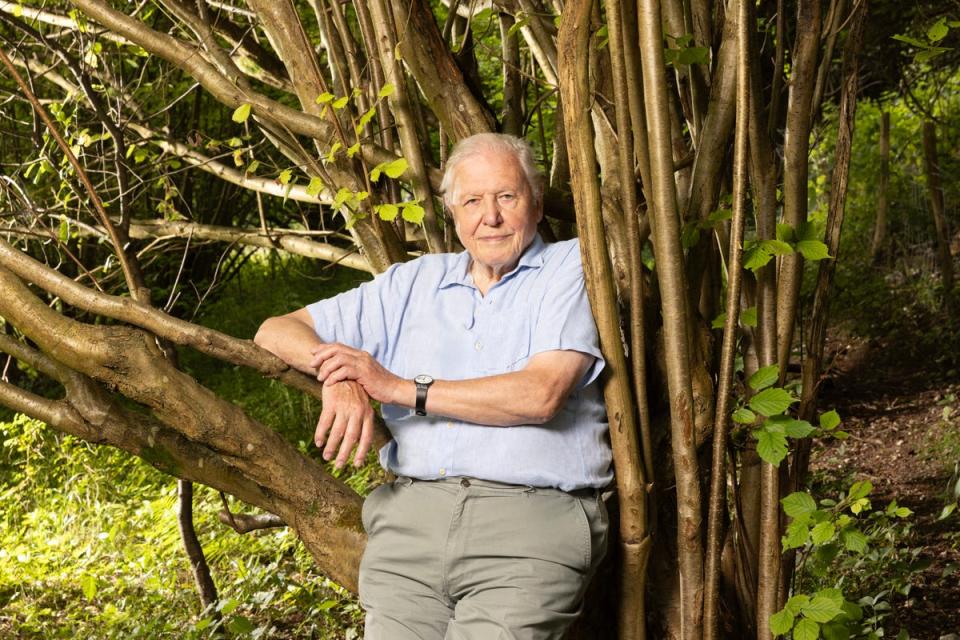

Thirty-six years ago when Mike Gunton joined the BBC’s Natural History Unit as a young, enthusiastic producer at the start of his career, he was told he would be working on David Attenborough’s latest programme. happened Trials of Life, was a study in animal behavior, and Attenborough, then in his sixties, thought it was time to stop. “Well, that seems pretty funny now,” says Gunton. “I don’t know how many TV series he’s done since then, but there must be at least 20. May it last a long time.”

The pair have worked together for almost four decades – Gunton is now 66 and Attenborough is 97 – and their latest project Planet Earth IIIThe series will be broadcast with its last episode this evening. Just like the previous two series, which aired in 2006 and 2016, this series showed us amazing stories from across the animal kingdom; From a baby ostrich searching for its mother in the Namib desert, to a group of brave seals driving away. Great white sharks off the coast of South Africa. But it’s a new element of the show, and a message that is increasingly appearing in Attenborough’s other programmes: this series is about how animals are forced to adapt, to survive, to the challenges they face in a world changed by humans.

“I’ve done a lot of shows in my life, but this is definitely a big deal,” says Gunton. It feels like we’re still getting Planet Earth “We get the tingle because it gives us wonderful things about nature, but it also says something about being sensitive to how much we weigh on our planet.” Planet Earth III This certainly demonstrates our negative impact on animal life (turtles on Australia’s Raine Island, for example, are dying en masse as temperatures rise). But it also shows how we are innovating to make things better (where the right whale was hunted to near extinction 40 years ago, the number has risen again to around 12,000 with the ban on commercial whaling). “Observing the natural world right now is very interesting and also a little worrying. But there are also parts of this that give you hope, and these need to be reflected in the programs.”

In some ways, a lot has changed since Gunton and Attenborough started working together. Attenborough wasn’t a fan of drones when they first arrived on the scene. They kept breaking down and he had to take countless walks through a meadow or forest while the camera on the drone zoomed in and revealed his location. “He’s a convert now and thinks the drone is an absolutely key, groundbreaking development in terms of the perspective it can give you on what’s going on in nature,” Gunton says. Advances in technology have been tremendous over the decades. “He has been amazed by the progress we have made in how we use robotic cameras,” adds Gunton. “We can take viewers beyond where the human eye can reach.”

Someone asked me, ‘What are your memories of him?’ One of the most important things I would say is that we roll around and laugh, sometimes talking about the absurdity of the world and the absurdity of what we do.

In other respects nothing has changed. There have always been, and always will be, stories of the “passion for courting birds” in Attenborough programmes. “There’s a row in Planet Earth III “It’s about the tragopan, a very strange bird that lives in China and has a very complex and strange courtship display,” says Gunton. “I think it’s never been filmed in the wild. Of all the things we showed David, that’s what made his eyes sparkle.” Gunton says Attenborough has always been “funny.” “Someone asked me, ‘What are your memories of him?’ “One of the most important things I would say is that sometimes we roll around laughing about the absurdity of the world and the absurdity of what we do. He’s a great storyteller.”

So is Gunton. We’ve gone well beyond our time slot on Zoom, and I can tell he happily tells stories for hours about his and Attenborough’s adventures (I hear he sent Attenborough into battle with warrior-like termites in Nigeria, and the pair sat surrounded). butterflies in Kent’s Downe Bank nature reserve). Gunton didn’t always think he’d go into the field of natural history – he initially wanted to become a social documentary filmmaker – but during his time as a zoology student at the University of Bristol, a palaeontology professor took him under his wing and he became an “obsessed” student. After going to Cambridge to study for a PhD in zoology He then returned to Bristol to work for the BBC’s Natural History Unit, where he is now creative director.

Over the years, he says, Attenborough’s “curiosity remains absolutely boundless.” When Gunton visits Attenborough’s home in Richmond, “he’ll have a pile of books he’s reading and working on at the piano. ‘Have you read this?’ he will say. Did you see that?’ This is a type of permanent scholarship. He’s very busy. It’s crazy. He’s away at this event, he’s away at that event, and he’s in a library here, and his energy is astounding.”

To prove it, he tells me a story. during filming Green Planet, The movie, released last year, included a scene in which Attenborough gave a presentation on a rowing boat on a lake in Croatia. Gunton, three decades Attenborough’s junior, was supposed to do most of the rowing when the cameras were not rolling, but Attenborough was having none of it. He jumped into the rowing chair at the first opportunity. “I will row. No, no, I will. Gunton remembers him insisting. “We started getting competitive because he was a rugby player in college [in Cambridge] So was I. I was saying, ‘Look, I’m a rower.’ He said, ‘No, we rugby players, we can row as well as you.’ So, as a 94-year-old, he rowed that boat for about a mile, and it was a big, heavy boat. “It’s not that hard to work with him in his nineties because he can do almost anything.”

While Attenborough tends to be on the field less and less these days, Gunton says his influence on the series goes far beyond his narrative. “That was his format ever since he did it. Life on Earth [in 1979]. So these shows are effectively tweaking or playing around the edges of that format, while its DNA has always been there. Gunton says that with every shot, every story in the series, he thought about the question: “How will David tell this?” He will also share ideas with Attenborough and seek his advice on more difficult scenes.

Attenborough is the right man to ask this. He has forever been the greatest influence on nature programming. His playful storytelling kept us immersed in the oddities of everything from spindly weeds on the ground to tiny sea angels in the ocean. Seeing nature in this awe-inspiring way taught us about the wonders of the world and the need to protect them. And many more – most recently, Morgan Freeman offering the lesser Life on Our Planet on Netflix – failed to replicate its magic.

The last time in a series that Attenborough properly went on location and did some challenging scouting. Green Planet. “We went to Costa Rica, America, the deserts of Central and South America,” Gunton says. “And we went just outside the Arctic Circle in Finland and into Slovenia. He loved it. We were talking beforehand about how many days we would have and we said it might be around three weeks in total. And his daughter, who he often worked with, was there and said: ‘Look, you’ve got to be careful, don’t do too many days.’ And when she went out to make us a cup of tea, she turned to me and whispered, ‘Actually, let’s do it for a few more days!’ This actually sums it up. “He was 94 years old.”

Gunton struggles to imagine a future in which Attenborough does not guide us through the natural world. “Forty years ago I was a new kid in the Natural History Unit,” he says. “And they said, ‘Of course this is David’s last series, so we have to think about who will take over.’ And it’s something people have been talking about ever since. “I think it’s one of those things we passed when we got to the bridge, but right now it looks like it’s running on six cylinders.”

He laughs as he admits he “cheekily” asked Attenborough if he was going to retire. Attenborough’s response? “I don’t know what that word means.”

The final episode of ‘Planet Earth III’ will air on Sunday, December 10 at 18.20 on BBC One.