Sign up for CNN’s Wonder Theory science newsletter. Explore the universe with news about fascinating discoveries, scientific advancements and more.

It’s noon and the sun is high in the sky, a natural cyan canvas covered with puffy cauliflower-shaped clouds. With the slightest warning, the clouds covering the horizon begin to disappear before your eyes. Soon after, the world begins to darken as the golden sphere that sustains life on Earth quickly disappears.

During that brief period during which the Moon passes between the Earth and the Sun, blocking the star’s rays and causing it to momentarily disappear for those best able to witness this rare event, these puffy, white masses will disappear and reform. but when the sun returns triumphantly.

At least that’s what scientists expect to happen in parts of Mexico, Canada and the United States during the total solar eclipse on April 8. If weather conditions permit, residents of the 49 U.S. states where a partial eclipse is expected may also see some clouds disappear.

During an eclipse, shallow cumulus clouds begin to disperse at large rates when they cover only part of the sun, and they do not reform until the end of the event, according to a study published Feb. 12 in the journal Nature Communications Earth & Environment. . The findings also suggest that this phenomenon may have implications for sun-blocking climate solutions such as solar geoengineering.

However, this does not mean that your vantage point on the upcoming eclipse will be cloud-free, as the research cannot be applied to all clouds; There is only a shallow cumulus type floating on land.

“These are low, patchy, puffy clouds that you would normally find on a sunny day,” said Victor Trees, a doctoral candidate in the department of earth sciences and remote sensing at Delft University of Technology in the Netherlands, who led the study. “If you see these puffy clouds on the day of the eclipse, look closely because they may disappear.”

eclipse effect

The new paper found that when only 15% of the sun is covered, low-level cumulus clouds begin to disappear in large numbers over cooling land surfaces. Although awareness of this phenomenon is not new, the evidence to support it and provide clarity on timing is new, according to the study’s authors.

“People have seen this from the field before. … If you are standing on the surface of the Earth, you can count the clouds and then watch them disappear,” Trees said.

But he added that it is never known exactly at what moment clouds begin to react to blocking sunlight. “It’s very difficult to determine when you’re standing on the Earth’s surface because clouds are constantly changing shape and size.”

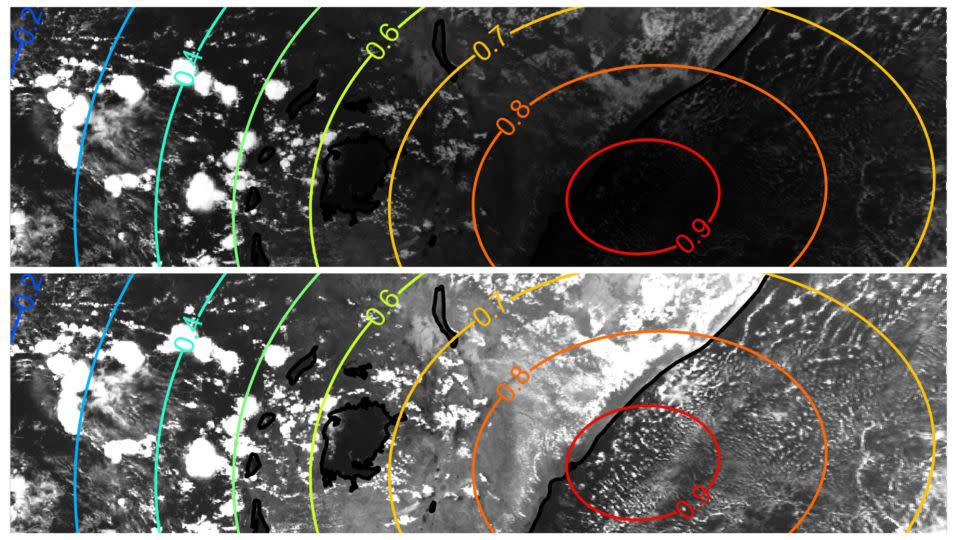

So Trees and his colleagues decided to study them from above using satellites. Satellites measure sunlight reflected from Earth, and scientists can derive properties of clouds from reflected sunlight. But previous similar studies had never taken into account the moon’s shadow during the eclipse, Trees explained; This was a necessary step to analyze the clouds normally hidden in the moon’s shadow.

The research team focused on data collected during three solar eclipses that occurred over Africa between 2005 and 2016. They discovered that cumulus clouds disperse during eclipses due to the relationship between solar radiation and cloud formation processes.

Trees explained that during the eclipse, the surface cools rapidly because the moon’s shadow blocks sunlight, preventing warm air from rising from the Earth’s surface, a key component in the formation of cumulus clouds. According to simulations, the process of rising air that leads to the formation of clouds generally takes about 15 to 20 minutes.

This means that even if you see the clouds disappear when the sun is already partially occluded by the moon, the origin of this effect has already been initiated.

“When there is still plenty of light outside and people often don’t realize a solar eclipse is happening, the clouds are already changing,” Trees said, noting that the atmosphere is already affected when there is minimal dimming.

“And then, with a delay, you see it in the clouds.”

‘Fundamental component of the climate system’

Clouds are much more than water droplets floating in our sky, they are indispensable elements of our atmosphere. Not only are they an important part of the water cycle, they also help control the Earth’s energy balance and influence the planet’s climate.

Shallow cumulus clouds in particular serve a critical function. These boundary layer clouds, or clouds in the lowermost part of the atmosphere most affected by the Earth’s surface, are common around the world and in the world’s oceans and occur occasionally throughout the year. They don’t tend to produce rain, but certain conditions can make it easier for them to develop into cloud forms. They are also very effective at reflecting sunlight back into space.

Shallow cumulus clouds are among the better understood clouds, according to research scientist Jake Gristey of the Cooperative Research Institute for Environmental Sciences (CIRES) at the University of Colorado Boulder; This is partly because they are low-altitude liquid clouds. Relationship between shallow cumulus clouds and solar radiation.

“The reason this study focused on shallow cumulus clouds is that sunlight reaching the (Earth’s) surface really has a direct effect on the evolution of these particular cloud types, in a way that is not true for other cloud types,” he said. Gristey, who has nothing to do with the paper.

Typically, when the sun rises in the morning, the intensity of sunlight increases, causing the temperature of the land surface to increase. The warmer land then heats the near-surface air directly above it, causing the air to rise in an upward draft, where it expands and condenses to form clouds. They usually last throughout the afternoon and dissipate when the sun sets in the evening.

Gristey said the eclipse provides an opportunity “that doesn’t actually occur under other conditions” to study the effect of rapid change in sunlight intensity on solar-heated clouds.

“It’s important that we understand the processes that (cause) these clouds to form and persist because they are an important component of the climate system,” he said.

But exactly what the role of shallow cumulus clouds is when it comes to a rapidly warming climate remains a long-standing issue of uncertainty in the scientific community. Add an eclipse to the mix and things get even more complicated.

“There’s a lot we don’t know about clouds, their behavior and evolution during eclipses,” said Kevin Knupp, a professor in the department of atmospheric and earth sciences at the University of Alabama in Huntsville, who was not involved in the study himself. participated in the study.

What’s new and notable about the paper, Knupp said, is that it uses more data to correlate the cooling caused by the eclipse with the reduction in cloud cover.

Climate geoengineering debate

Study co-author Stephan de Roode, associate professor at Delft University of Technology, said the new findings regarding the high sensitivity of shallow cumulus clouds to an eclipse-induced reduction in solar radiation warrant further research on proposed solar geoengineering techniques.

Studying the impact of global warming on clouds, de Roode said, “We need to ask whether geoengineering techniques aimed at reducing solar radiation over much longer time scales could potentially lead to changes in global cloud patterns.”

Scientists have spent decades studying how best to tackle the idea of reducing the planet’s temperature through solar geoengineering techniques, one of the world’s most controversial climate solutions. The decrease in cloud cover may be an unexpected consequence of some basic techniques aimed at hiding the sun, according to the authors of the new paper.

“If you reduce solar radiation, for example, by a certain amount, then the effective fraction of solar radiation that you receive at the ground surface will actually be more than you would expect because you have fewer clouds,” de Roode said.

“This means that even though you try to reduce the amount of radiation with geoengineering techniques, more solar radiation can still reach the Earth’s surface,” he said, adding that this feedback effect could make such techniques “less efficient.”

Others aren’t so sure. “I think we need to be a little careful. CIRES’ Gristey said a lot more work is probably needed to tie the results of their study to geoengineering proposals.”

Gristey added that one part of this research that he acknowledged needs further investigation is the “very different time scales” when comparing the duration of the eclipse with several proposed solar geoengineering methods. “For example, even if aerosols were injected into the stratosphere…those aerosols would remain in the stratosphere for much longer than the several hours we see during a solar eclipse,” he said.

De Roode hopes those preparing for the next solar eclipse in North America remember to keep their eyes peeled for the disappearance of low-lying cumulus clouds. Even some of the millions of people outside the exact path of the eclipse may notice the clouds disappearing that day, if weather and geographic conditions permit.

“I hope everyone will look curiously at the sky during the eclipse to see if what we found for Africa is the disappearance of shallow cumulus clouds, and whether Americans are also observing this in their own country,” he said.

“This is such an amazing phenomenon.”

Ayurella Horn-Muller He has reported for Axios and Climate Central. He is the author of “Devourer: The Extraordinary Story of the Vine Kudzu That Devoured the South.”

For more CNN news and newsletters, create an account at CNN.com